Wicked Cool Overlooked Books #4: The Museum Book: A Guide to Strange and Wonderful Collections

January 7th, 2008 by jules

January 7th, 2008 by jules

Not only is the Wicked Cool Overlooked Book series Colleen Mondor’s brainchild, but I also have her to thank for telling me about this book, released in September of last year by Candlewick. You’ll see at the end of this post excerpts of and links to other reviews, meaning you can argue its under-the-radar-ness with me, but it’s true that there haven’t been any reviews of it in Blogistan (as my husband calls it) — none that I can find anyway — so I’m stickin’ to my decision to feature it today.

Not only is the Wicked Cool Overlooked Book series Colleen Mondor’s brainchild, but I also have her to thank for telling me about this book, released in September of last year by Candlewick. You’ll see at the end of this post excerpts of and links to other reviews, meaning you can argue its under-the-radar-ness with me, but it’s true that there haven’t been any reviews of it in Blogistan (as my husband calls it) — none that I can find anyway — so I’m stickin’ to my decision to feature it today.

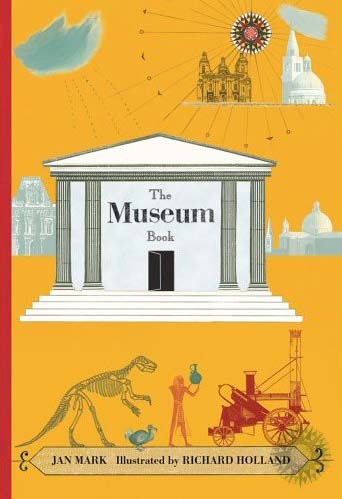

Geared at the 9 to 12 age range, The Museum Book: A Guide to Strange and Wonderful Collections is a 51-page book in picture book format that I would argue would also work quite well with high schoolers interested in history, particularly your collectors and curator-wannabes. It was written by Carnegie Medal-winning Jan Mark, one of Britain’s most distinguished children’s book authors, who passed away about two years ago. If you’ll allow me a quick digression here, this obituary at Guardian Unlimited, for whom she reviewed books, is a good read. And I love this first sentence, reminding me of the whole idea behind Wicked Cool Overlooked Books and the second sentence just making me laugh:

She would often draw attention to books which had not benefited from lavish marketing campaigns, or were from small presses or from publishers overseas. But she was scathing about the large numbers of children’s fantasy novels she was sent for review, most of which she dismissed as “hoop-tedoodle,” a word defined as “inflammation of the story caused by infectious or toxic writing.”

Mark takes the very essence of the idea of a museum and expounds upon it. After an introduction written from the second-person point-of-view, which effectively snags the reader (“Suppose you went into a museum and you didn’t know what it was. Imagine: it’s raining, there’s a large building nearby with an open door, and you don’t have to pay to go in. It looks like an ancient Greek temple. Temples are places of worship, so you better go in quietly”), she takes us back to 550 BCE to Princess Bel-Shati Nannar and what was, for all intents and purposes, the first museum in the lost city of Ur, where the Muses lived. Part of the book’s many charms is that Mark never skips over a thing; she takes that opportunity to explain in lucid, yet never condescending, terms who the Muses were. Then we hit the Middle Ages — the alchemists, apothecaries, and Wunderkammer (the Chamber of Wonders, or the “cabinets of curiosities”). Chapter Four takes us on a journey through the sixteenth century, Mark pausing to explain the compulsions of collectors (“People who collect, no matter what the objects . .. . want to get them all, a full set”), and introducing us to collectors Ulysse Aldrovandi, Elias Ashmole, Edward Harley, Robert Cotton, and Peter the Great — the odd collections (teeth, stuffed crocodiles) he both created and purchased. Chapter Five brings us to the eighteenth century and the opening of the British Museum (thanks to the collections of Ashmole, Cotton, Harley, and Sir Hans Sloane). Explaining how some remarkable buildings and even towns can become museums in themselves, Mark later takes us to the Chrysler Building, Venice, and Williamsburg, Virginia, to name a few examples. And don’t forget a dictionary. Yes, “{e}very time you open a dictionary, you are entering a museum of WORDS.”

Chapter Six touches upon Catherine the Great and Carl von Linne’s system for classifying plants and animals, as well as the definition of a “synoptic” gallery or museum. Chapter Seven takes us to some “famous fakes,” the battle over the Elgin Marbles, and the controversy over exhibiting items such as the shrunken heads of South America and Egyptian mummies. And the final chapter essentially wraps it all up with commentary on how museums have benefited societies over time and what we learn from them. The final page is damn-near eloquent (and quite poignant, knowing it was Mark’s final book before her death) with her thoughts on how memory is our museum, our cabinet of curiosities that “will never be full; there is always room for something new and strange and marvelous. It will never need dusting”:

. . . there is another kind of collection that everyone has, including you. It is in your head. Everything you have ever seen, heard, smelled, tasted, or touched is in there. Most of it has been pushed to the back, like the things in storage in a real museum, but an enormous amount is still there when you need it. You can get it out and have an exhibition whenever you want; you can spend as long as you like wandering around it. As you get older, many things that you did not understand when you first stowed them away suddenly start to make sense. Bring them back up from the basement. Now you know what they are.

Mark writes in such an engaging, often humorous, and thoroughly lucid manner. It’s a joy to read from front to back. And the book is illustrated by Richard Holland, who uses a mixed media approach, using print and collage. And it really works, complementing well the detailed prose of Mark. A couple of his spreads require the reader to turn the book sideways, such as the spread about the almost-seven-feet-tall Peter the Great, “hard to miss.” Spreads like that are hard to miss, too, but Holland does it well. Instead of overpowering the text and trying too hard to say, look what I can do as an illustrator, thus making too much of a spectacle of himself (which is a risk when one has to turn the book sideways to take in images or text), Holland makes it work, never overpowers, and only does it when called for. His choices on when to use collage and when to not work well, too, using real images for iconic museum pieces, such as the skull of Piltdown Man (thought for years to be the “missing link” fossil between humans and apes but, decades later, proven to be a hoax) and for historical figures (Catherine the Great), yet using his own drawings and paintbrush for others (such as, the horse upon which he places Catherine). These are detailed illustrations with often very minute figures — much for readers to pore over and take in.

Mark writes in such an engaging, often humorous, and thoroughly lucid manner. It’s a joy to read from front to back. And the book is illustrated by Richard Holland, who uses a mixed media approach, using print and collage. And it really works, complementing well the detailed prose of Mark. A couple of his spreads require the reader to turn the book sideways, such as the spread about the almost-seven-feet-tall Peter the Great, “hard to miss.” Spreads like that are hard to miss, too, but Holland does it well. Instead of overpowering the text and trying too hard to say, look what I can do as an illustrator, thus making too much of a spectacle of himself (which is a risk when one has to turn the book sideways to take in images or text), Holland makes it work, never overpowers, and only does it when called for. His choices on when to use collage and when to not work well, too, using real images for iconic museum pieces, such as the skull of Piltdown Man (thought for years to be the “missing link” fossil between humans and apes but, decades later, proven to be a hoax) and for historical figures (Catherine the Great), yet using his own drawings and paintbrush for others (such as, the horse upon which he places Catherine). These are detailed illustrations with often very minute figures — much for readers to pore over and take in.

So, for what it’s worth, I’m shining a light upon this title, highly recommended for history, art, and mythology lovers, as well as amateur and even serious collectors, especially those who want to share their passion with their children. I’d say this is a must-have for middle school and high school libraries. An absorbing read.

Note: The Washington Post did a short feature on this title as “Book of the Week” here in November, calling the book “a wunderkammer of its own, with fascinating facts and detailed drawings” (I believe you register to read that, but it’s free).

You can also read here the starred Publishers Weekly review: Mark “demonstrates the fundamentally eccentric nature of institutions more commonly viewed as sober and staid . . . Holland, also British, jolts readers still further with his mixed-media collages, which sparingly employ color and liberally combine what look like Victorian engravings, pencil sketches, Gorey-like figures, and photos of various locales. His stylish compositions play with perspective, type and design, making excellent use of the vertically oriented pages as the text pieces together an overview of museum evolution.”

The Observer wrote last April, “{t}here could not be a more marvellous memorial of Jan Mark, who died last year, than The Museum Book . . . illustrated with bright elegance by Richard Holland. This is an argument she must have wanted to make. There is nothing dustily didactic about it. It is a passionate, unpatronising, offbeat paean to museums and multiplicity . . . And she concludes, poignantly in the context of her death, that our memories are museums too.”

Finally, Colleen covered this title at Bookslut as well in her December feature/round-up, “Curious Minds”: “What you really have here, in this beautiful book, is the story of a lot of eccentric people and places. It is about individuals with a burning desire to know as much as they could about something or everything, and how that curiosity fueled the collecting of piles and piles of stuff that eventually ended up in museums

. . . the very nature of curiosity is celebrated . . . a{n} unusually fun book about a usually academic subject and while Mark deserves a lot of credit for writing about what seems a staid subject in a fresh and modern way, illustrator Richard Holland deserves a boatload of credit for his fantastic accompanying illustrations.”

I’m so glad you got this one! I love love love it! It’s one of the most beautiful and unique books on museums that I’ve ever read and I totally think that anyone interested in the subject would enjoy it. It’s a wonder and it so totally deserves all the attention it has gotten and more!!

Ooh! Remind me to pick this one up at the library, please!

Cool! I can’t wait to read this one–I was intrigued when Colleen mentioned it and now I really want to check it out…Thanks!