Seven Impossible Interviews Before Breakfast #64

(the Nonfiction Monday Edition): Steve Jenkins

February 4th, 2008 by Eisha and Jules

February 4th, 2008 by Eisha and Jules

In 2007, School Library Journal described author/illustrator Steve Jenkins as a “master illustrator,” and you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who didn’t agree with that. Steve — pictured here with his son on a summer road trip (“my mother said I look like a street person,” Steve told us. “My daughter granted, more kindly, that I could pass as a bohemian poet”) — has illustrated thirty nonfiction books for children, eighteen of them written by himself or co-authored with his wife, Robin Page. And the science teachers and librarians of the world are happy about this, because Steve’s books are titles that impart facts but do so in an enticing and entertaining way and with his signature eye-popping torn-and-cut paper collages.

In 2007, School Library Journal described author/illustrator Steve Jenkins as a “master illustrator,” and you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who didn’t agree with that. Steve — pictured here with his son on a summer road trip (“my mother said I look like a street person,” Steve told us. “My daughter granted, more kindly, that I could pass as a bohemian poet”) — has illustrated thirty nonfiction books for children, eighteen of them written by himself or co-authored with his wife, Robin Page. And the science teachers and librarians of the world are happy about this, because Steve’s books are titles that impart facts but do so in an enticing and entertaining way and with his signature eye-popping torn-and-cut paper collages.

Listed here at Steve’s web site is a biblio-

Listed here at Steve’s web site is a biblio-

graphy if you’re inter-

ested in becoming more familiar with his titles (and don’t miss his thoughts on science as well). Whether he’s depicting animals, or parts of animals, in striking spreads that show their actual size; joining forces with Robin to present a guessing game, a series of visual riddles on how animals use their tails, noses, ears, feet, mouth, and eyes or showing us the various ways animals move; or even taking us to the top of the world’s highest mountain, he is addressing his child readers with clarity yet never condescension and and opening up worlds both microscopic and monumental in what the Tampa Tribune calls Jenkins’ “signature medium . . . richly colored and brilliantly designed.”

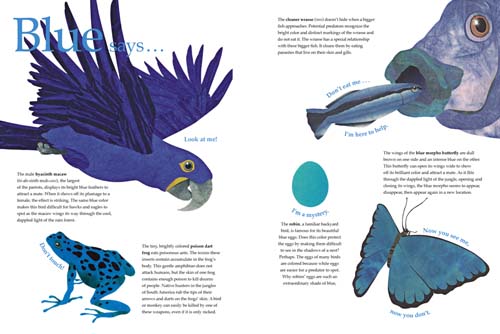

This year for the Cybils Awards, three Jenkins-illustrated titles have been shortlisted: Vulture View by April Pulley Sayre in the category of Nonfiction Picture Books (also recently named a 2008 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award Honor Book); Living Color, which he wrote, shortlisted in the same category (“a prime choice for any young animal enthusiast’s collection,” wrote Publishers Weekly in their starred review); and Valerie Worth’s Animal Poems, shortlisted in the Poetry category (which I reviewed here back in July at 7-Imp). In their starred review of Animal Poems, a “superlative collaboration {which} will resonate with poetry lovers, but should also open doors for those who feel daunted by poetry,” School Library Journal wrote,

This year for the Cybils Awards, three Jenkins-illustrated titles have been shortlisted: Vulture View by April Pulley Sayre in the category of Nonfiction Picture Books (also recently named a 2008 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award Honor Book); Living Color, which he wrote, shortlisted in the same category (“a prime choice for any young animal enthusiast’s collection,” wrote Publishers Weekly in their starred review); and Valerie Worth’s Animal Poems, shortlisted in the Poetry category (which I reviewed here back in July at 7-Imp). In their starred review of Animal Poems, a “superlative collaboration {which} will resonate with poetry lovers, but should also open doors for those who feel daunted by poetry,” School Library Journal wrote,

“{p}resented on beautifully designed spreads, the offerings are animated by Jenkins’s exquisite artwork. Whether eye-catching or subtly understated, his designs respectfully bear out each poem’s image.”

Steve agreed to an interview for the Cybils blog, an abbreviated version of what you’ll read here, posted last week. What follows is the interview in its entirety. We at 7-Imp — and everyone over at the Cybils’ site — thank him for taking the time to give us some insight into his work.

7-Imp: You have a long and impressive career of making beautiful, engaging non-fiction books. Children’s book author and America’s first National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jon Scieszka, talks through his Guys Read effort about how teachers and librarians can sometimes, whether inadvertently or not, be rather dismissive of non-fiction and how perhaps we could do a better job of acknowledging non-fiction, especially for boy readers. Do you have any thoughts on that?

7-Imp: You have a long and impressive career of making beautiful, engaging non-fiction books. Children’s book author and America’s first National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Jon Scieszka, talks through his Guys Read effort about how teachers and librarians can sometimes, whether inadvertently or not, be rather dismissive of non-fiction and how perhaps we could do a better job of acknowledging non-fiction, especially for boy readers. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Steve: In my experience, teachers and librarians have not been dismissive of non-fiction, though that may be because I’m usually interacting with a self-selected group of non-fiction fans. In fact, that’s so obvious I don’t know why I never thought of it before.

I agree with Jon. I think there are several things going on. Many early education professionals come from a language arts or “soft” science background, such as sociology (I’m not using “soft” in a negative way), rather than from a ‘hard” science (physics, chemistry, biology) curriculum. Reading and analyzing fiction is an integral part of most teachers’ education.

I also think fiction and non-fiction elicit different kinds of passion in readers. The themes of fiction — love, fear, adventure, triumph over adversity — are universal. Read aloud, the exploits of Lilly or Despereaux can’t fail to captivate a room full of kids. The pleasures of non-fiction are more subtle. Few readers laugh out loud or cry as they learn about the extraordinary abilities of the jumping spider or how the continents have drifted about. And not all children are interested in the same non-fiction subjects. Some are fascinated by astronomy, others by geology or zoology. Unless a child has expressed interest in a specific subject, I think it’s much harder for a librarian to suggest a sure-fire non-fiction book.

More: there’s a canon of great childrens’ fiction. Awards, best-of lists, reviews, and blogs focus disproportionately on fiction. And there’s the shelf-life problem. Charlotte’s Web and My Father’s Dragon (two of our family’s favorites) have lost none of their appeal after more than fifty years. Almost any geology, astronomy, or biology book of that age will be hopelessly out of date in many important respects. Finally (whew), though I hate to say it, I think the bar is higher for children’s fiction. Too many non-fiction books are just collections of facts presented without context or passion.

More: there’s a canon of great childrens’ fiction. Awards, best-of lists, reviews, and blogs focus disproportionately on fiction. And there’s the shelf-life problem. Charlotte’s Web and My Father’s Dragon (two of our family’s favorites) have lost none of their appeal after more than fifty years. Almost any geology, astronomy, or biology book of that age will be hopelessly out of date in many important respects. Finally (whew), though I hate to say it, I think the bar is higher for children’s fiction. Too many non-fiction books are just collections of facts presented without context or passion.

But we shouldn’t let a few little things like that stand in the way of turning kids on to the world of non-fiction books. I’m serious. But I understand why it’s not always easy.

7-Imp: About your Cybils-nominated Living Color Jennifer Schultz of The Kiddosphere @ Fauquier wrote (at this post at the Cybils blog), “Jenkins shares information, rather than lectures, and readers feel as if they are being included in delightful secrets.”

I love that and think it captures well the strengths of the titles you both illustrate and write — or co-write with Robin. So, what’s your secret for delighting us and not lecturing to us? And what advice would you give aspiring non-fiction children’s book writers who want to learn how to do the same?

Steve: I don’t quite know how to answer this, because there certainly isn’t any secret. I have no formal training as a writer (or as a scientist either -– go figure). I find writing really hard. I rewrite many, many times. It’s a reductive process, and I try to take out what feels patronizing or confusing. I do have a reader of a certain age in mind (it varies with the book), and I try to anticipate questions children might ask. I know I get annoyed when I read something along the lines of: “The rhinoceros is the second largest land animal,” and the obvious next question isn’t answered. I also try to not put adults who might be reading the book on the spot by giving them answers, often at the back of the book, to questions that I think kids are going to ask. Finally — and I think this is the most important thing — I never write about something that I’m not fascinated by myself. This is true, I’m sure, of all good science writers. But I do read a lot of non-fiction that, while technically competent, was pretty clearly done in the spirit of a high school book report on a George Eliot novel (not to dis her . . .).

7-Imp: In your Boston Globe–Horn Book Award acceptance speech, you wrote, “{i}n my books, I try to present straightforward information in a context that makes sense to children. Children don’t need anyone to give them a sense of wonder; they already have that. But they do need a way to incorporate the various bits and pieces of knowledge they acquire into some logical picture of the world. For me, science provides the most elegant and satisfying way to construct this picture.”

There are innumerable ways to structure your non-fiction books in such a way that will provide this “logical picture of the world” (and you – and Robin — have been praised for your book design and organizational techniques, such as the use of sidebars of information which free you up to wow us with your art work, for instance). What is the first step for you in deciding how to organize your text and illustrations?

Steve: Organization is usually driven by the content of a book, though sometimes (rarely) we will have a certain organizational structure in mind and choose content that works with it. I See a Kookaburra is an example of the latter. We wanted to show a group of animals in exactly the same position on two spreads, hiding them in an environment on the first spread and revealing them on the second. Exploring different habitats became a vehicle for this structure.

Steve: Organization is usually driven by the content of a book, though sometimes (rarely) we will have a certain organizational structure in mind and choose content that works with it. I See a Kookaburra is an example of the latter. We wanted to show a group of animals in exactly the same position on two spreads, hiding them in an environment on the first spread and revealing them on the second. Exploring different habitats became a vehicle for this structure.

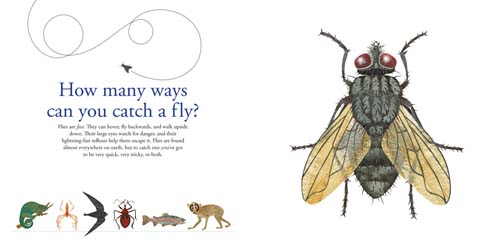

Typically, there is a lot of back-and-forth between the art and text — especially when it’s a collaboration with Robin. Ultimately, a kind of narrative develops. As we work, we decide just what we want to explain about a subject, and experiment with different combinations and sequences of words and images. A lot of this is trial and error, and we will create eight, ten, sometimes as many as twenty dummy layouts trying to figure out what works best. Some of it is stylistic -– I might be determined to illustrate a particular animal, whether it makes complete sense or not. Usually Robin will gently talk me out of this kind of self-indulgence. I rarely use diagrammatic illustrations (if you don’t count scale comparisons). Diagrams can be a wonderful way to communicate complex information (David Macaulay comes to mind). It’s just that I like to create a different kind of illusion with the art.

One simple technique we’ve used a number of times is based on reading to and with our kids when they were younger. It involves two levels of text, one that can be managed by a beginning reader and a second that can be read by a more proficient reader, or aloud by an adult if a younger child is interested in finding out more.

7-Imp: What was it like to collaborate with your wife, Robin Page, for the first time in 2001 on Animals in Flight? Were there any surprises there?

7-Imp: What was it like to collaborate with your wife, Robin Page, for the first time in 2001 on Animals in Flight? Were there any surprises there?

Steve: Robin and I have our own graphic design studio, and we have been working together for a long time — 25 years or so by the time we did that book, so there were not many surprises. It’s never been hard for us, I think because we have very different ways of solving problems. I’m very linear, and Robin makes intuitive leaps. It’s fun, and we make each other better.

7-Imp: Vulture View by the talented April Pulley Sayre was nominated for the Cybils in the same category as Living Color. Tell us briefly the pros and cons, if any, of illustrating someone else’s text as opposed to writing your own or working with Robin. What is the collaboration process like when working with other authors? Do you typically work hand-in-hand throughout the entire process of the book’s creation, or is a text for you to illustrate as you see fit simply handed over to you?

Steve: I did correspond a few times with April as I worked on Vulture View, but that was really more the exception than the rule. Typically, I get a manuscript that’s already been through at least a first edit. Editors control the process pretty tightly. Not that an editor has ever suggested that I don’t speak to an author, but in my experience it’s been clear that the editor (and art director) are the people who must be pleased. They may show an author work-in-progress, but I’ve never had an author contact me directly with a request to change anything. Occasionally, I’ve asked for a small change in the text that allows me to solve a design or illustration problem. It’s curious, really. I understand why the system is set up this way, but coming from the world of design, which is a very collaborative discipline, it has always seemed like a bit of a lost opportunity. I think that’s one reason I enjoy the books that Robin and I do together so much.

It is easier, in a way, to illustrate another author’s book, because I don’t have to keep questioning whether the text is okay or the concept presented clearly enough. Or if the whole idea even makes sense. I don’t think, however, that I’d illustrate a book by another author unless I thought it worked. Ultimately, the most satisfying books are the ones I write (or write with Robin) and illustrate.

7-Imp: On that note, was it thrilling or challenging — or both — to collaborate with your father on 2004’s Next Stop, Neptune: Experience the Solar System? You’ve talked in interviews before about how your physicist father encouraged your interest in science and art as well, particularly since he was a “frustrated artist” himself. I love that he encouraged both sides of your brain. I don’t know that there’s a question in here, except to say: Can you talk about that a bit and what it means to you now as a children’s illustrator who creates books about science?

7-Imp: On that note, was it thrilling or challenging — or both — to collaborate with your father on 2004’s Next Stop, Neptune: Experience the Solar System? You’ve talked in interviews before about how your physicist father encouraged your interest in science and art as well, particularly since he was a “frustrated artist” himself. I love that he encouraged both sides of your brain. I don’t know that there’s a question in here, except to say: Can you talk about that a bit and what it means to you now as a children’s illustrator who creates books about science?

Steve: It was a lot of fun to work with my father. The book was his idea, and I went for it immediately. Though it’s impossible for me to sort out all the influences and congenital tendencies that have made me a children’s science book author, I’m convinced that my father played an important role by nurturing my early interest in science. I think I got to art and design more on my own, though I imagine that seeing my father paint and draw influenced me as well.

7-Imp {illustration pictured here is from Vulture View}: You have created a most definite signature style with what School Library Journal called your “neat, sharp-edged paper collages and pure, simple colors.” Have you ever, by chance, wanted to break away from an easily-recognizable style and try something like, say, oil paints? Or do you find this particular medium the most fitting and most rewarding for you and/or your subject matter? (We, your devoted and nerdy fans, are happy you’re doing paper collage, but I thought it’d be worth asking. To hear Steve Jenkins, by chance, say, I’ve just always wanted to try a book in chalk would be wild, indeed).

7-Imp {illustration pictured here is from Vulture View}: You have created a most definite signature style with what School Library Journal called your “neat, sharp-edged paper collages and pure, simple colors.” Have you ever, by chance, wanted to break away from an easily-recognizable style and try something like, say, oil paints? Or do you find this particular medium the most fitting and most rewarding for you and/or your subject matter? (We, your devoted and nerdy fans, are happy you’re doing paper collage, but I thought it’d be worth asking. To hear Steve Jenkins, by chance, say, I’ve just always wanted to try a book in chalk would be wild, indeed).

Steve: I did a lot of drawing, painting, printmaking, and photography before I got to collage. I would like to draw more — maybe even paint — but just for myself, not for publication. I honestly don’t think I have much to offer the world in those media. There are so many people who do it so well . . .

7-Imp: Book Buds’ Anne Boles Levy, Cybils Co-Founder and Editor, has this to contribute: “Okay, this is process porn: how do you put one of your sublime illustrations together? Do you start with a sketch or photograph? How do you choose which papers to use, how to get the right shapes and effects. Walk me through the whole thing. I like to live vicariously.”

We know you cover some of this at your site with your wonderful “Making Books” feature, but you can talk about that here anyway, for those who haven’t seen that informative presentation?

Steve: Sure . . . let’s assume we’re talking about a portrait of an animal. I begin with a very rough “thumbnail” sketch –- usually a lot of them — exploring the reader’s point of view, how the subject will fit on a page, and where text might go. If it’s a book I’m doing with Robin, she often does these early studies. The next step is to find reference images. I collect photos and illustrations of my animal in books (we have a pretty big library of natural history books, and we’re always adding to it), on the internet, or in photos that I’ve taken at zoos or museums. Robin does most of this if the book is a collaboration. From these reference images (typically a dozen or so) I’ll make my own composite sketch. I find it’s important not to trace, but to draw freehand. The little (or not so little) distortions that creep in give the drawing a kind of energy that a tracing never seems to achieve. Once I have a sketch I like, I redraw it (it’s OK to trace my own sketch), making decisions about where the edges of different sheets of paper will be. Shading doesn’t work — I have to commit to a definite line, since I’ll be cutting a sheet of paper. As I work on this drawing, I’m looking at my papers (organized by color in a big flat file) and deciding what colors and patterns I want to use. There is often an element of surprise at this point. I rarely know ahead of time what paper I’m going to use for a particular creature, and I may find a paper works in some unexpected way to evoke fur, feathers, skin, or whatever. When my outline drawing is complete and I’ve picked out the papers with which I want to work, I photocopy the drawing a number of times. These copies will be my patterns for cutting out each individual piece of paper for the illustration. I use a two-sided adhesive film, removing a protective covering from one side and adhering it to the back of my color paper. Cutting through the Xerox and the color paper at the same time with an exacto knife gives me a color-paper shape that I’ll stick down on a board or color background. Of course, I have to work from the bottom up. Some small, simple shapes -– eyeballs and the like — can be cut freehand, without a guide. The adhesive is not repositionable, so I have to be confident about what I’m sticking down and where it’s going. Some illustrations come together beautifully. Others I may do several times before I get them right.

7-Imp: Kelly Fineman of Writing and Ruminating, Cybils ’08 Poetry Organizer, reviewed the Cybils-nominated Animal Poems at her blog this year and wrote:

Steve Jenkins’s artwork throughout the book is simply spectacular. The jellyfish has a translucence to it that shines through, even though he’s made it from paper. The porcupine (one of my favorite images) is convincingly prickly, but with a spot on his snout, just above his nose, that looks so velvety soft that I actually want to pet it. The hummingbird, while made of paper, looks as though its wings and tail are made for actual flying. And the groundhog — well, he’s cuter than any paper animal has a right to be. He appears to have been made from a particularly furry sort of paper, and but for a bit of a glint in his eye that appears to be a warning and some pretty sharp (and long) claws, he’d be the perfect object of a good cuddling.

Here’s Kelly’s interview question: “I guess my curiosities and questions stem from that review excerpt: How do you manage the translucent effect with the jellyfish (vellum?) and the furry effect in other places? Do you make your own papers? How does the printmaking/photographing process work to so effectively make an object dimensional (unless, of course, they’re digital all the way and just that convincing)?”

Here’s Kelly’s interview question: “I guess my curiosities and questions stem from that review excerpt: How do you manage the translucent effect with the jellyfish (vellum?) and the furry effect in other places? Do you make your own papers? How does the printmaking/photographing process work to so effectively make an object dimensional (unless, of course, they’re digital all the way and just that convincing)?”

Steve: The translucency comes from the papers themselves. I have many beautiful Japanese rice papers (that jellyfish is made of one). The furry effect comes from tearing rather than cutting, and produces different effects with different papers. Tearing is a trial and error process, not always easy to control.

I don’t make my own papers, though recently Robin taught me how to make paste papers and I’ve been experimenting with that. It’s about painting the surface rather than actually working with pulp to make a sheet of paper. The birds’ wings in Vulture View are done with some of the paste papers we made.

7-Imp: Little Willow of Bildungsroman, the Cybils ’08 YA Coordinator and interviewer extraordinaire herself, wants to know: What intrigues you personally that you’ve yet to make a book topic?

Steve: I’ve got a list. Some could easily be children’s books, others would present quite a challenge:

The relationship of scale and form in the natural world. For example, strength increases as the square (cross-sectional area) of linear dimension, but volume (weight) increases as the cube. This has all kinds of implications for animals and the way they live.

Parasites. They’ve evolved extraordinary ways of manipulating their hosts (including humans) to get what they want.

Microfauna. There is an incredible, savage world in our backyards, filled with terrifying predators, venomous creatures, gentle herbivores, and more. Most are too small to see with the naked eye.

Prehistoric mammalian megafauna, those neglected creatures that came after the dinosaurs and before recorded human history. I just read about one just today — a “guinea pig” the size of a bull. It lived in South America.

The nature of conciousnesss.

How the world might end.

7-Imp: Can you tell us about any new titles/projects you might be working on now?

7-Imp: Can you tell us about any new titles/projects you might be working on now?

Steve: A book about the ocean — mostly the deep ocean.

A book about time. Not timekeeping, but our subjective sense of time.

A book about dangerous animals that, at first blush, don’t seem so scary.

7-Imp: We know this is considered a cliché question, but as book lovers, it interests us: What books or authors and/or illustrators influenced you as an early reader?

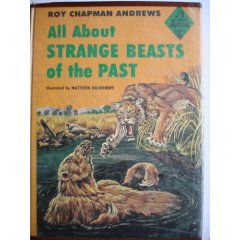

Steve: I loved a book called All About Strange Beasts of the Past by Roy Chapman Andrews. It’s about the author’s search for fossils in Mongolia. I liked Kipling — The Jungle Book was one of my favorites. I went through a tall tales phase (maybe the 5th grade?): Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, those guys. In middle school I was a science fiction fan — Ray Bradbury, Andre Norton, Robert Heinlein. Around this time I also read everything I could find about the Holocaust, Hiroshima, the Armenian genocide and various other sad chapters in human history. I’m not sure why — I was a happy child.

Steve: I loved a book called All About Strange Beasts of the Past by Roy Chapman Andrews. It’s about the author’s search for fossils in Mongolia. I liked Kipling — The Jungle Book was one of my favorites. I went through a tall tales phase (maybe the 5th grade?): Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, those guys. In middle school I was a science fiction fan — Ray Bradbury, Andre Norton, Robert Heinlein. Around this time I also read everything I could find about the Holocaust, Hiroshima, the Armenian genocide and various other sad chapters in human history. I’m not sure why — I was a happy child.

7-Imp: What’s one thing that most people don’t know about you?

Steve: I once ate an entire pecan pie in one sitting. And felt fine. That’s what being 21 will do for you.

7-Imp: If you could have three (living) illustrators or author/illustrators — whom you have not yet met — over for coffee or a glass of rich, red wine, whom would you choose?

Steve: Richard Dawkins, David Wiesner, Steven Pinker {pictured here}.

7-Imp: What is your favorite word?

Steve: “Daddy.”

7-Imp: What is your least favorite word?

Steve: “Dialogue” used as a verb.

7-Imp: What turns you on creatively, spiritually or emotionally?

Steve: Life (I don’t mean my life, though that is a bit of a turn on for me . . . but the phenomenon of life — of things being alive).

7-Imp: What turns you off?

Steve: Dogma.

7-Imp: What is your favorite curse word? (optional)

Steve: “Barn it” (a mispronunciation by one of our children at a tender age. It’s entered the family lexicon).

7-Imp: What sound or noise do you love?

Steve: A basketball touching nothing but net.

7-Imp: What sound or noise do you hate?

Steve: The telephone.

7-Imp: What profession other than your own would you like to attempt?

Steve: Somewhat realistically: Robotics.

Less realistically: Guitar god.

7-Imp: What profession would you not like to do?

Steve: Politics.

7-Imp: If Heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?

Steve: “Have you decided in what form you’d like to return?”

For more online information on Steve Jenkins:

- Steve’s web site.

- “A Q & A with Steve Jenkins” (abbreviated version of this interview); Cybils; January 31, 2008.

- “Steve Jenkins on Illustrating Natural Science,” an original movie from TeachingBooks.net (this link includes four great original interactive slide shows about the making of Steve’s and Robin’s books); 2008.

- Steve Jenkins biography at Brief Biographies; 2008.

- “Steve Jenkins, Cut Paper King” by Alison Morris; Publisher Weekly’s Shelftalker; October 2, 2007.

- Steve Jenkins: Author Program In-depth Interview (Insights Beyond the Slide Shows); TeachingBooks.net (.pdf file); November 3, 2005.

- “Rising Star” feature from The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books; 1998.

- Feature at American Scientist Online’s Bookshelf; Undated.

One of his books that is not pictured here (although man – you got a ton of his books in!) is my son’s favorite: “Dogs and Cats”. We have read it so many times! What I love about it is how well it explains the whole idea of species/type, etc.

He’s a wonder – we will certainly be getting many more of his books from the library (and Powells!)

Eisha and Jules,

Thanks for this fabulous interview with Steve Jenkins. What a talent he has for collage! His art is spare…yet has the ability to dazzle the eye.

I enjoy reading quality nonfiction for children–especially about topics in science. Steve’s books are definitely among the best being published.

I love, love, love his books! I’d say he creates a kind of visual poetry with his paper collages.

I am in heaven. Thanks for making my day with this great interview.

Thanks, you all. And making Tricia’s day? Priceless.

(Ick, now I sound like a credit card ad).

Colleen, yes, I love that book about dogs and cats, too. That link to my Animal Poems review also includes a review of Dogs and Cats. I believe I wrote it this past summer (and it includes a link to Fuse’s review of it, which was so good). I’m glad your son loves it. My daughters love his books, too. They’re fabulous.

(Here’s that link again).

A guitar god who can eat a whole pecan pie! (I think I’m in love.)

“Too many non fiction books are just collections of facts presented without context or passion.” This really says it all — why Steve’s books are so profoundly engaging, fascinating and simply beautiful to experience.

Thanks for this life-affirming interview. Faboo times one thousand!

God had better let him return as an illustrator. Even if he wants to be a polar bear or something like that. Not allowed.

Such a dazzling interview. His passion for life (“as in things being alive”) is contagious. He makes me want to know how every living thing works…

I swear, you guys keep moving the bar for interviews higher and higher. That was phenomenally well-done and well-presented. And could Steve Jenkins BE any more articulate and knowledgeable and giving? I think not.

Bravissimo!

Fabulous interview. You managed to hit so many of the fascinating features of his books. I am eager to see what he does with parasites in the future! He has a way with paper for sure.

Good interview! I look forward to tracking down Next Stop Neptune (and am glad it’s an older book so I don’t have to drum my fingers while waiting for my turn on the holds list). I too dislike “dialogue” as a verb. It reminds me of the phrase “engaging in loving dialogue” (which seems like an euphemism for telling someone s/he’s wrong).

[…] Steve Jenkins (interviewed February 4, 2008): “Too many non-fiction books are just collections of facts presented without context or […]

[…] Steve Jenkins and his torn- and cut-paper collages several times before, including this interview from over a year ago. I’ve made my fondness for his books quite clear. When I asked him […]

[…] “aficionado of animal behavior”), Steve Jenkins. He’s been here on a Sunday, for a full-fledged interview, and just last April, as well. Back during that interview in 2008, he said he was working on a […]

Love your books and so do my students. I teach third grade in Westerville, OH. I can’t stand the way testing has sucked the life out of the job I love. Picture books, chapter books, your book…save us all. Thanks so much! kmt

[…] make them accessible to students in the 2nd and 3rd grades as well. In addition, many titles offer “…two levels of text, one that can be managed by a beginning reader and a second that can be rea… Teaching vocabulary and assigning and modeling clearly defined tasks render the texts even more […]

[…] Sayre about her newest picture book, Eat Like a Bear (Henry Holt, October 2013), illustrated by Steve Jenkins. It’s so good, this book. April talks about the writing of it (“Language to me is […]

[…] Sayre about her newest picture book, Eat Like a Bear (Henry Holt, October 2013), illustrated by Steve Jenkins. What a good book it is, and I really enjoyed hearing April’s thoughts on the writing of it. […]

[…] Lieder (Candlewick, March 2015); and April Pulley Sayre’s Woodpecker Wham!, illustrated by Steve Jenkins (Henry Holt, May […]

[…] 2008 interviewer with the blog Seven impossible things for breakfastJenkins reflected on his career writing […]

[…] a 2008 interview with the blog Seven Impossible Things for BreakfastJenkins reflected on his career writing […]