Seven Questions (Times Two) Over Breakfast

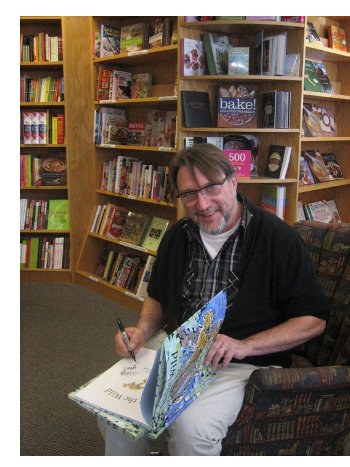

with Author David Elliott

November 16th, 2010 by jules

November 16th, 2010 by jules

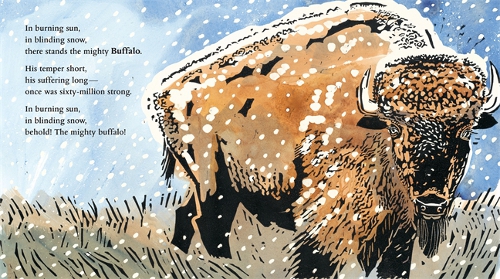

His temper short, / his suffering long — / once was sixty-million strong. /

In burning sun, / in blinding snow, / behold! The mighty buffalo!”

(Click to enlarge slightly.)

At his web site, children’s book author David Elliott writes, “Books are…about language: its rhythms and its music; its stops and its starts; its noises and its silences; its unending layers of meaning. I’m not always as successful as I’d like to be. Still trying to get it right.” I’d say David has gotten it right more than a few times. He has penned several picture books, as well as middle-grade novels for kids, many of which I have enjoyed over the years as a librarian and with my own children. (Here is a comprehensive list of his titles at his site.)

And there are many reasons I enjoyed this interview with David—I was quite enamored with his thought-provoking responses to several of these questions, for one—but the best thing that came out of it was re-discovering my love for his two poetry picture book titles, On the Farm and In the Wild, both illustrated by Holly Meade. The latter was released this August (Candlewick), and as I formatted this interview, I fell in love all over again with the poems in the book, as well as with Holly’s luminous woodcut and watercolor illustrations. The above spread is from this collection of verses. School Library Journal writes, “Elliott’s spare verses vary in length and form with bits of humor {and} some lovely use of language and imagery.” Elizabeth Ward wrote about the first collection of poems (The Washington Post), “Elliott’s little verses pack a deceptive punch.”

David’s here for a breakfast interview. I’ve got the cyber-coffee on, and we’re ready to chat. I thank him for stopping by to talk about a little bit of everything regarding his work as a children’s book author and poet — humor in children’s books, the joy of having a good editor, the art of listening, not undervaluing children, the challenges of writing picture books for the very young, the “imposter syndrome” of a writer, how prose picture books are like eggs, what is most liberating to him in his writing, and (my favorite part of all) still feeling as scared and awed by the world as he did as a kid. Oh, and lots more . . .

Jules: Can you talk about the genesis of the two poetry titles, On the Farm and In the Wild)? And, on that note, what was your inspiration for the Evangeline Mudd tales?

David: Several years ago, I was invited to participate in an event honoring the fabulous children’s book maven, Kirsten Cappy of Curious City in Portland, Maine. Writers were asked to contribute a short piece; illustrators provided art to accompany it. I chose the robin as my topic—who knows why? perhaps because Kirsten is a famous redhead—and challenged myself to say as much as I could about the bird in the fewest number of words. On the Farm grew out of that experience. (The original poem about the robin didn’t make it into the book, by the way, but is being recycled in another companion book also with the incredible Holly Meade, On the Wing.) In the Wild seemed like a natural companion to the homey, domesticity of the farm book.

Evangeline was originally a totally different story. No primatologists, no apes. I was about a third of the way into the book and hitting a wall. Didn’t know where to go next and the narrative was very stubborn about telling me. Not a good sign. Just about that time, younger friends of ours were expecting their third child. Through the miscalculations of all concerned, the baby arrived when the parents were walking in the forest surrounding their home, and, well, she was born in the New Hampshire woods. In winter. I started wondering what a girl who was born al fresco might be like and realized that this was the real Evangeline. I put those early pages aside and started over. Oh well. (That baby, by the way, was just fine. A happy ending all around.)

On this topic, inspiration, I love what the late Octavia Butler had to say: “Habit is more important than inspiration.”

Jules: Discuss any pressure you may have felt, if any, in writing a sequel of sorts to On the Farm.

David: Like many writer friends, I suffer from the imposter syndrome. “Okay,” I tell myself, “I wrote that book, but it’s very doubtful if I’ll be able to pull off the next one.” These feelings are legitimate, I guess. Every book, like every child, is idiosyncratic. None of the old rules apply. This is especially true for novels, by the way.

But In the Wild presented different challenges. First, there was the problem of choosing which animals to include. Farm was much easier in that regard, since a farm is, in fact, a container holding a particular set of animals that we all agree belong there. (We hear “farm”; we think cow.) But there is no such container for wild animals. They live all over the world in every possible habitat, and there are thousands of them. It took a lot of trial and error (mostly error), trying to come up with the right combination of fourteen. Thank god for the wisdom of my wonderful editor at Candlewick, Liz Bicknell.

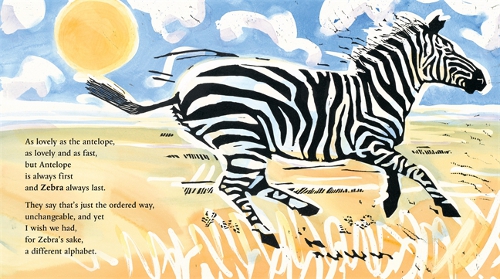

A rather larger problem was that it soon became clear that I knew very little about these animals beyond the superficial. To correct that, I read a great deal and looked at a lot of images. Even so, my initial draft of a poem almost always seemed to focus on the obvious. My first go at the zebra for example was about -– guess what? Stripes! Very humiliating. Liz encouraged me to say something new. (Let me say it again; thank god for good editors!)

“As lovely as the antelope, / as lovely and as fast, / but Antelope / is always first / and Zebra always last. / They say that’s just the ordered way, / unchangeable, and yet /

I wish we had, / for Zebra’s sake, / a different alphabet.”

(Click to enlarge slightly.)

Finally, there was the enormous challenge of writing a book for a young audience about animals that could become extinct in their lifetime. It seemed irresponsible to say to children, “Tough luck, kids! Your world is changing! Get used to it.” At the same time, it seemed very wrong not to find a way to acknowledge the truth. To complicate matters further, I also wanted to give children a choice about how much they wanted to know concerning the worrying plight of so many of these animals. I tried to integrate these conflicting ideas through the last poem, the polar bear, hoping it would reverberate back through the book.

It may sound strange or even pretentious to say it, but having written those verses, I feel much more closely connected to these animals. It was a gift, really. I’m very, very grateful to have been given the opportunity.

Jules: You talk at your site about how many of your books are humorous. Is it a major brain shift for you to switch from that kind of writing to this beautiful, spare poetry?

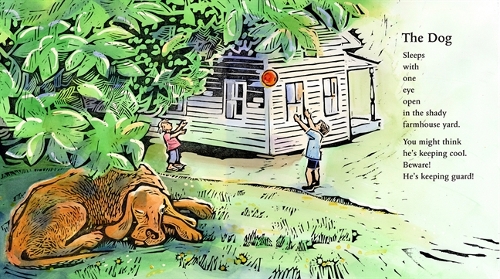

“Sleeps / with / one / eye / open / in the shady / farmhouse yard. / You might think / he’s keeping cool. / Beware! / He’s keeping guard!”

(Click to enlarge.)

David: First off, thanks for the kind words, especially because until On the Farm, reviewers almost invariably described my work as “quirky,” something that used to drive me crazy, but which I now embrace. Is it a major brain shift? No, I don’t think it is. No matter what I’m writing, I’m trying to demonstrate for young readers the power and the beauty, the resilience and the play in their language. I hope that doesn’t sound too high-falutin’. Understand, too, I’m not saying I always succeed, but it is something I try to be conscious of as I work.

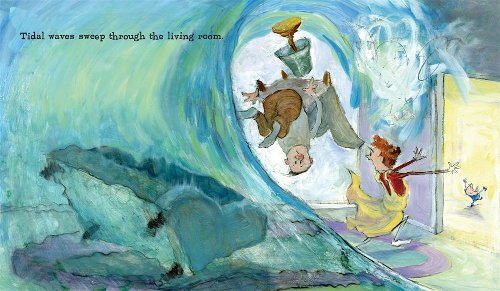

(Candlewick, 2009)

(Click each spread to enlarge)

I will say that I wish humor weren’t so undervalued in our culture. I don’t know where we got the idea that tragedy is somehow more . . . hmmm . . . what’s the right word? Literary? Valuable? Meaningful? than comedy. To me this seems very provincial. I sometimes wonder if the children’s book world isn’t suffering from an inferiority complex. “See?” we seem to be saying to our counterparts who are writing, editing, publishing for adults. ”Children’s books are Literature with a capital L, too. We write all the time about people dying, alcoholic and drug-addicted parents, anorexia, depression, etc.” Is it possible that we’re trying to foist off our own disappointments about life onto our children by giving them so many of what I now (snidely) think of as “Oh-dear! Mother-is-dying-of-leukemia!” books? This seems not only wrong, but cruel. You know, I’ve read reviews of my own work and others’ that say something like, “this book is good for children with a sense of humor,” as if the ability and desire to laugh is a kind of disability, something perhaps to be tolerated but pitied. Children understand how contradictory, hypocritical, pompous, and just plain silly the adult world can be. I think it was Gail Sheehy, the author of Passages, who adopted an AmerAsian child, a girl who had lived through the horrors of the war in her country, Viet Nam. In trying to understand how the child survived, Sheehy suggested that it was the girl’s ability to laugh at the absurdity of her situation. My own childhood was a difficult one. I know that the books that I loved most were those that made me laugh. I knew, as do many kids, all I needed to about suffering.

I know I’m going to regret saying all this in public.

Jules: What was it like to see Holly’s art work for the first time for both titles?

David: I shouted. Both times. What else could I do? I couldn’t be luckier than to have been paired up with Holly Meade.

Jules: Will there be a sequel to Jeremy Cabbage, by chance?

David: I hope so. I have it roughly sketched in my head, and by “roughly,” I mean I have a relatively good idea of who will people the book and the setting. Also, the beginning scene. As you might know, the book is currently in development at Fox 2000. The executive producer and the producer are the same two smart women who made The Devil Wears Prada and are cooking up some very exciting ideas for the movie. It’s not 100% yet, but we’re getting closer. If the movie is made, I hope I’ll get someone interested in a sequel. As my Islamic friends say, “In-Sha’-Allah.”

Jules: What was your road to publication?

David: I would describe my road to publication as unpaved and full of potholes. I’m still traveling on that road, by the way. Where’s the Motel 6?

Jules: Can you tell me a bit about your writing process/”craft”? Do you outline plot before you write or just let your muse lead you on and see where you end up? How different is it for a prose picture book, compared to poetry?

David: I think my process is best described in this famous quote from EL Doctorow: “Writing is like driving a car at night. You only see as far as your headlights go, but you can make the whole trip that way.” Sometimes, when I am maybe half way through the first draft of a novel, I might try to scribble some notes so that I can give myself the illusion that I know how to proceed. Sometimes, too, when I’m ready to quit for the day, I’ll leave the last sentence unwritten, so that I’ll have something definite to write on that blank screen the next morning. Silly, I guess, but it works. All in all, though I wish it were otherwise, my process is very desultory. To me, a lot of writing is the art of listening, listening to the story as it tells itself to you.

I sometimes think of prose picture books, at least the ones I like, as eggs. Really nutritious. Really simple. And really strong. You know that thing about trying to break an egg by placing each end in either palm and squeezing? You can’t do it. But if there’s a crack in the shell, you’d better have your dry cleaner’s number handy. That’s what I aim for. No cracks. I love the challenge of writing a picture book for the very young. It’s terribly difficult, at least for me, but satisfying if I can get it right.

I sometimes think of prose picture books, at least the ones I like, as eggs. Really nutritious. Really simple. And really strong. You know that thing about trying to break an egg by placing each end in either palm and squeezing? You can’t do it. But if there’s a crack in the shell, you’d better have your dry cleaner’s number handy. That’s what I aim for. No cracks. I love the challenge of writing a picture book for the very young. It’s terribly difficult, at least for me, but satisfying if I can get it right.

The poetry books completely possess me. Once I start, I’m no good for anything until I’ve finished. No matter what I’m doing—driving, feeding the dog, responding to an interview—part of me is thinking of the poems, trying to get all the elements, the rhythm and music, the diction, the line breaks to fall into place until the sum is greater than the whole (or whatever that expression is.) This drives my wife crazy, but it’s the only way I know how to do it. It’s miserable, really. Currently, I’m finishing up the edits and writing some new poems for On the Wing, the book I mentioned earlier. I might be typing right now, answering these questions, but what I’m thinking is, what rhymes with albatross?

Jules: How do your school visits inform your writing, if at all?

David: I love school visits, because these days they’re almost the only contact I get to have with kids. They inform my work by consistently reminding me not to undervalue children. But they also anger me. What would our country be like if we valued our schools, our teachers, and our kids as much as we valued our posturing? What if we spent as much money educating our children as we did fighting? Which is the better investment? Which would make a better world?

David: I love school visits, because these days they’re almost the only contact I get to have with kids. They inform my work by consistently reminding me not to undervalue children. But they also anger me. What would our country be like if we valued our schools, our teachers, and our kids as much as we valued our posturing? What if we spent as much money educating our children as we did fighting? Which is the better investment? Which would make a better world?

Jules: I know this question is probably considered cliché, but as a book lover, it interests me: What books and/or authors had an especially significant impact upon you as an early reader?

David: Alice in Wonderland, hands down. I still love Dickens, too, especially Bleak House, Oliver Twist, and Great Expectations. And I love Robert Louis Stevenson. Just last night, I pulled Kidnapped and Treasure Island off the shelves and put them on my bed stand. How many times have I read them?

I can still remember the thrill of reading some of those books that I ordered through elementary school from whatever the equivalent of Scholastic was in the Ice Age (when I was in school. Or maybe it was Scholastic? Can Scholastic be that old?): No Children, No Pets; Wild Geese Flying; Danny Dunn and the AntiGravity Paint; Island Boy.

As an adult, I think Tuck Everlasting is possibly the best middle grade book ever written. That and Sideways Stories from the Wayside School.

I’m still impacted by everything I read. Right now, I’m in the middle of The Famished Road, a novel by the Nigerian writer, Ben Okri. Amazing! And I just finished a non-fiction book, Salvation on Sand Mountain about American religious sects who handle snakes. I couldn’t put it down. All of these, in one way or another, will find their way into my work.

I’m still impacted by everything I read. Right now, I’m in the middle of The Famished Road, a novel by the Nigerian writer, Ben Okri. Amazing! And I just finished a non-fiction book, Salvation on Sand Mountain about American religious sects who handle snakes. I couldn’t put it down. All of these, in one way or another, will find their way into my work.

Jules: Okay, so this sounds cliché, too, but I still think it’s a good question: What advice would you give to aspiring children’s poets and/or picture book authors?

David: Well, I wouldn’t presume to give advice to anyone, since I myself feel like I have to reinvent not just the wheel but the idea of revolution every time I start a book. But I know from my own experience that in writing verse you can’t get away with anything, so don’t try to sneak anything by, an off-meter or a forced rhyme. Everything—and by everything, I mean everything—has to serve the poem. Not the poet. It’s a hard lesson to learn.

The prose picture books I admire most are those that are really spare. Currently, I teach in the low residency MFA Program at Lesley University. I often find myself saying to my students. “Good! But can you tell the story with half the words?” I also say this to myself, by the way, so it’s not just an exercise in torture for my students. Oh, one more thing. Don’t forget about the architecture of the narrative. This is especially important in the picture book.

In general, I might add this: Readers don’t care how much we may love to write, or that our spouses or teachers or grandchildren tell us we are good at it. They don’t care that writing is therapeutic for us, or that we feel we have to write. Readers don’t care about our feelings. And why should they? The only thing readers care about is what’s on the page. That’s it. To me, this is very liberating.

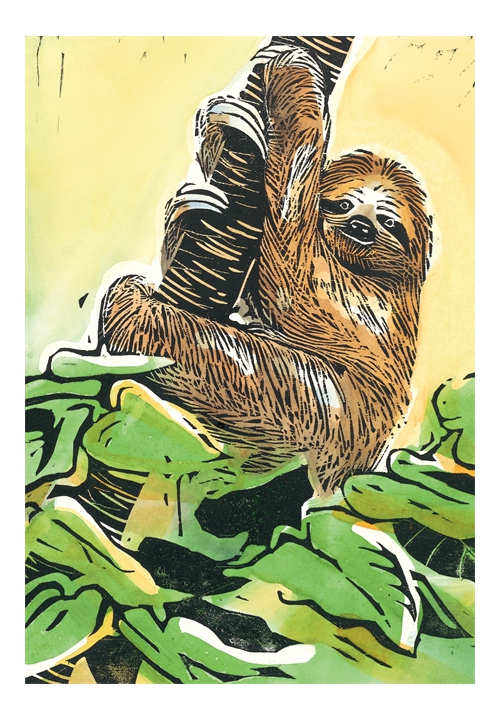

“I have affection / for the Sloth, / though she’s small / and rather hairy. /

Brown, the color / of a moth, / she only moves / when necessary.”

Jules: Are you working on any new projects that you can tell me about?

David: Well, I hope within the next week to have finished On the Wing. (Albatross . . . Betsy Ross? Auchinsloss? Dental floss? Aaaargh!) Before that, there will be another Meade/Elliott publication from Candlewick. Under the Sea. Next year, I think.

I’m still trying to find the right voice and structure for a middle grade novel that I’m committed to, but can’t get right. I’ve been working on it for over a year. It’s very discouraging. And I have a YA novel started that I hope to get to within the year. A couple of picture books. I have many ideas backed up. I hope I can find the time to get to them.

Jules: If you could have three (living) authors (or even illustrators)—whom you have not yet met—over for coffee or a glass of rich, red wine, whom would you choose?

David: Only three? Okay. Natalie Babbitt, because even though I’ve read Tuck many times, I still tear up when I read that Prologue. My god! That prologue! Sue Townsend, because even though I’ve read The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Age 13¾ many times, I still laugh out loud when I pick up the book. And Michael Rosen, another Brit, because as Children’s Laureate of England, he founded the Roald Dahl Funny Prize. I’d like to thank him.

Jules: What’s one thing that most people don’t know about you?

David: Yikes! Sometimes, I’m so indiscrete that I sometimes feel that everybody knows everything about me. Let’s see . . . Okay. How about this? Even though I am an adult and fulfill (most of the time) all the attendant responsibilities of the adult world, in my heart I still find life as terrifying and as wonder-filled as I did as a kid. As beautiful and as ugly. As ridiculous and as filled with meaning. I envy those people who seem to have so much confidence, to have it all figured out. To me, it’s still a mystery. All of it.

Jules: Is there something you wish interviewers would ask you – but never do? Feel free to ask and respond here.

David: Not a question, exactly, but I’m struck by all the falderal there is about the world of writing for kids, the industry that’s grown up around it, and all the adults who profit from it (myself included) in one way or another. Yet, there seems to be so little serious conversation about kids themselves. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, there are fourteen million children living in poverty in the United States. Fourteen million! Not in some third world country, but right there under our noses. This is shameful! Imagine if we were to gather those fourteen million kids and their families in one city? When it comes to kids, we are a third world country. And what about the influence of the corporate world on our children? Don’t get me started.

But even if we’re not comfortable talking about the politics of kids, I guess I’d like to see more conversation about kids themselves. I’ve heard other authors say that writing for kids is no different from writing for a general audience. I don’t understand this. Children are not just little versions of us. Think of the difference between someone forty-five and someone fifty. Not much. But the difference between a three-year-old and a six-year-old? A six-year-old and a nine-year-old? And even teenagers still have one foot in the landscape of the imagination, while struggling to plant the other in the hard soil of reality. Brain research tells us that the brain isn’t fully developed until what? Twenty-five or so. And I think I read somewhere that one reason teens are at such a risk for suicide is because their brains haven’t yet developed the capacity to think into the future. With all that going on, it seems to me the responsibilities of writing for these people are different, because there’s so much more at stake. To me, it’s impossible to think or talk about writing for kids unless you are thinking and talking about children themselves.

Jules: What is your favorite word?

David: “Yes.”

Jules: What is your least favorite word?

David: “No.”

Jules: What turns you on creatively, spiritually or emotionally?

David: Music. Especially Mozart, Handel, and Bach.

Jules: What turns you off?

David: Meanness.

Jules: What is your favorite curse word?

David: I appreciate a good F-bomb once in a while.

Jules: What sound or noise do you love?

David: My wife’s singing.

Jules: What sound or noise do you hate?

David: My neighbor’s weed-wacker. (But I like my neighbor.)

Jules: What profession other than your own would you like to attempt?

David: I’d love to be an opera singer. Or a modern dancer. Or a painter.

Jules: What profession would you not like to do?

David: I don’t think anyone would want me to be an airline pilot. Or a surgeon either, for that matter.

Jules: If Heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?

David: “David! You’ve finally lost those thirty extra pounds.”

IN THE WILD. Copyright © 2010 David Elliott. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

ON THE FARM. Text copyright © 2009 David Elliott. Illustrations copyright © 2009 Holly Meade. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

FINN THROWS A FIT. Text Copyright © 2009 by David Elliott. Illustrations Copyright © 2009 by Timothy Basil Ering. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

Author photos provided by David Elliott.

The spiffy and slightly sinister gentleman introducing the Pivot Questionnaire is Alfred. He was created by Matt Phelan, and he made his 7-Imp premiere in mid-September. Matt told Alfred to just pack his bags and live at 7-Imp forever and always introduce Pivot. All that’s to say that Alfred is © 2009, Matt Phelan.

Great interview–I am so excited to hear about two more Elliott/Meade collaborations coming out. And now I’m going to have to hunt down more of David’s work. I only know Farm and Wild and love them both.

Love what David has to say about kids not caring about anything but what’s on the page. So true, and so hard to remember when I’m in the middle of actually writing. They won’t care about everything it was painful for me to leave out. I’m cutting a chapter book right now and am going to tape that quote on my laptop!

Thanks, you guys!

great, i found this very encouraging and inspiring

Very interesting interview, funny and humorous.

Thanks for this inspiring, fascinating interview. I love, love In the Wild. Now I will have to get the backlist. Thanks.

Great interview. I have to say, as a writer, I understand the “imposter syndrome.” But, David Elliot, an imposter? Never. This guy is the real deal.

I was sorry to see that he didn’t mention The Transmogrification of Roscoe Wizzle, which remains one of my favorite David Elliott books of all time.

My writing is about buffalo country too (but after the buffalo), so I enjoyed that illustration. Also Bleak House is my favorite Dickens book, so I’m always happy to see its power infusing other authors.

I also appreciate him introducing politics and the Children’s Defense Fund. The kids reading these books live in the real world, and his concern for them is admirable.

Thanks all.

Lara, Save that cut chapter. It might come in handy later (even in another book.)

Did you know there is another David Elliot (this one with one t only) who is also a children’s literature star, particularly for his illustrations which includes illustrations for the Redwall series and Margaret Mahy’s poetry anthology. Have a look at his work at http://www.davidelliot.org

David!

What a wonderful interview. When you mentioned Adrian Mole, I was transported back to Adolescent Lit and the good times! I can’t wait to get my hands on your books, I find that teaching poetry to 7th graders is best done by showing them that it can be FUN and about anything…they all think it has to be so serious and dark!

Happy holidays!

Thanks Krystal. So proud of you!

[…] to the fish! The Bubble People! Fish! …”– Spread from David Elliott’s And Here’s to You! (Candlewick, 2004)(Click to enlarge […]

[…] artwork has also appeared here and here at 7-Imp. Her watercolor collages in Susan Campbell Bartoletti’s 2011 picture book, […]

[…] illustrator Rob Dunlavey visits to talk about illustrating David Elliott’s In the Woods (Candlewick, April 2020), a poetry collection that explores 15 creatures in […]