Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlight #4:

Maurizio Quarello’s take on Bluebeard

January 27th, 2011 by jules

January 27th, 2011 by jules

(Click to enlarge cover.)

Jules: It’s time to welcome again Cristiana Clerici (pictured here) for another international picture-book spotlight. And today she treats us all to an Italian illustrator and French book.

Jules: It’s time to welcome again Cristiana Clerici (pictured here) for another international picture-book spotlight. And today she treats us all to an Italian illustrator and French book.

As a reminder, these posts are all Cristiana’s doing, since I asked her last year to stop by 7-Imp when the mood strikes her to show us what is happening in contemporary picture books over in Europe. In this case, it’s one Italian illustrator’s take on the demented, bloodthirsty aristocrat Bluebeard of the classic tale by Charles Perrault. In case you missed it earlier, to get the low-down on what I’m calling Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlights, visit this page of the site.

I thank her kindly for contributing today. You can click on each image below to super-size it and see in more detail.

Cristiana:

c’è in agguato una belva.

Alda Merini (1)

In those few lines by the great Italian poet, who died about a year ago, is fully contained the essence of Blue Beard’s drama: the moment of pathos lived by his last young wife, imprisoned in a reality that suddenly falls on her with all its weight.

Blue Beard is a well known story: it’s the story of a man we would most probably call a serial killer and a woman who, first of all, is the victim of her naïveté, of her thirst for social fulfillment, of her curiosity, and then of the man everybody is afraid of.

What really makes a difference in this picture book, published by the prestigious French publisher Milan Presse, are its illustrations by Maurizio Quarello.

Maurizio is a master illustrator, gifted with incredible explanatory skills and an enviable pictorial technique. In his representations he is extremely versatile. He can give voice to every story with uniqueness, letting the tale lead the way, adapting his technique to narrative needs: we saw him passing from the mellow density of Babau Cerca Casa, Toni Mannaro, and Le Voyage de la Femme Éléphant, to the almost absence of colour of Les Arbres Pleurent Aussi, where his delicate and poetic narration almost tiptoes on the text, to end up with the more comic-oriented setting of Effets Secondaires, just published by Le Rouergue.

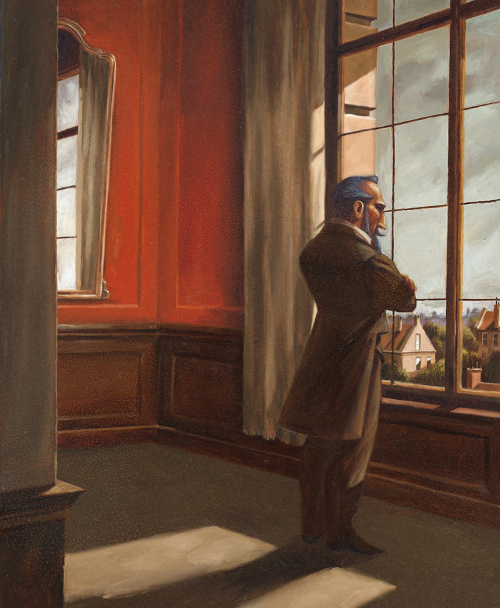

In this picture book, Maurizio lets transpire all his love for cinema. If you asked me to give a definition of this book, I shall say it’s a cinematographic picture book, where Ivory’s romantic atmospheres or those of the last Pride and Prejudice by Wright shine through. It’s an artwork where everything is movement; stillness, likewise.

Every image represents a moment seized and crystallized in a frame, going well beyond the page. Every table, even those apparently more silent, tell about a growing pathos that will culminate in the defeat of the terrible Blue Beard.

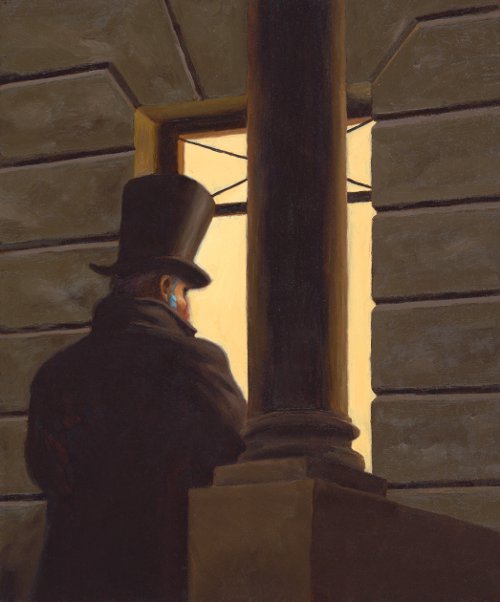

The narration starts with an emblematic image: Blue Beard looks thoughtfully out of the window, winded up in the light that shines shyly through clouds charged with rain, presentment of imminent disasters. We see him in the act of observing his unaware victim, almost lying in ambush. We can sense her unawareness, her last moments of innocence, she, who still doesn’t know what the future will hold for her. We observe them, newly married, on the carriage that will take them into their new lives. Then nothing but the emptiness of a long corridor in the shade, alluding to a dreadful mystery. And then, after a non-defined lapse of time, we can see her friends entering the house, taking advantage of the dreaded husband’s absence to finally sneak into a private room that arouses envy and curiosity; we see the young wife opening the forbidden door, victim of her own curiosity, discovering at last the macabre secret hidden behind her husband’s blue beard.

The key stained with blood stands alone, clear evidence of the young woman’s guilt and only witness of her dreadful discovery, hanging over like a silent exposure of her female weakness in front of prohibition. The husband arrives home in a mantle of obscurity.

From this point on, events succeed rapidly, dramatically so, and the tables give full dynamism to the action: Blue Beard discovers the truth, and he accuses his wife and condemns her to death, like he did with his other wives. Image-narration, which up to this moment had been consecutive and descriptive, now seems to be abruptly changing course by introducing disturbing image pauses that considerably contribute to increased dramatic tension. Perspective-changes, frequent and sudden, give the story a particularly vigorous intensity.

After Blue Beard has pronounced his deathly sentence, the illustrator surprises us once more by transporting the scene out of Blue Beard’s apartments, changing completely the atmosphere: in a temporal suspension similar to that of a soaring bird, the bride’s sister appears in the act of looking out of the window of her room. Were it not for the text, we would only sense the clear sky and spring-time with its suspended stillness. It’s the central image of the narration, the turning point that allows us to breathe and to feel hopeful again, an image that, for that light grace and for the intensity of the moment it describes, reminds me of the poetry of Keats.

But it’s just a moment, because we are immediately trapped in a vortex of dreadful events that leads us to the climax of the story.

Quarello uses cinematographic techniques with enviable skill. He masters them with ease, as if his job were film director and not illustrator. From shot and reverse shot, to zoom, to image pause, it seems his illustrations are not meant to stop with the page’s boundaries, as if they wanted to drag us into the whirlpool of events. And this is exactly what happens.

His paintings strongly recall Hopper and the Romantics’ atmospheres: from the colour palette he chooses, to the polished density of his brush strokes, to his way of playing with lights and shades, to the portrayed subjects. The unexpected framings, always astounding, characterize his images.

Once again, a masterpiece you shouldn’t miss.

If you like Maurizio Quarello, stay tuned. More news soon.

(1) Aforismi e Magie by Alda Merini with drawings by Alberto Casiraghi, Rizzoli Publishing, November 1999. “Behind each longed freedom / there’s a beast ambush.” Alda Merini was a famous Italian poet, notorious for her sarcastic, though romantic, vision of life. She was a singular woman, who lived her life always being true to herself with dignity and wisdom, a most beloved poet.

Barbe Bleue by Charles Perrault, illustrations by Maurizio Quarello, Collection Albums Classiques, © 2010 Éditions Milan. Images have been reproduced with the publisher’s permission. Any reproduction forbidden.

This is such an interesting story to choose to tell – not an easy one I think for kids. But maybe this book is aimed at adults? Hopper is definitely who I thought of looking at the pictures. Thanks Cristiana.

Zoe, I wondered that, too. The publisher’s page for the book at their site says, “ÂGE : DE 5 À 10 ANS.” My high school French is weak, but I assume that means 5 to 10. This brought to mind the question of whether or not Europeans (or perhaps I should be more specific and say just the French?) read the more brutal/gorey tales to their children, whereas most American parents do not. That’d be an interesting question to explore, I think.

Bookbird 2005, Vol 43, no. 1 has an article “A Challenge to Innocence – ‘Inappropriate’ Picturebooks for Young Readers” by Carol Scott might be of interest to you Jules. I came across it because I’m currently writing about Nordic picture books in translation and I noticed that there are many many books from Sweden than from other Nordic countries. Discussions with colleagues suggested that among other things this may be because Swedish kidlit is just the “right” amount of challenging for an anglosaxon audience, as compared to eg Danish books that often (apparently) cover topics that wouldn’t be seen in English language picture books aimed at kids eg prostitution and abortion. Someone did comment that they thought the same could be said of French picture books but I haven’t yet explored that.

Zoe: Wow. Interesting. That’s true about Sweden (and I tend to love those Swedish picture book titles that make it here) — that is, we tend to see a lot of those titles. I’d love to read that article. Thank you for the heads-up!

p.s. Quarello’s Bluebeard looks particularly terrifying, especially on that cover. The sneer, though, on the final illustration Cris sent is pretty hair-raising, too.

Also, this is a wonderful reminder for me to get a Bookbird subscription already.

Jules asked for my opinion, so here goes. I’m not an expert on Danish children’s books, and I don’t know about abortions, but one of the most popular Danish titles is called (my translation!) “The mole who wants to know who took a shit on his head.” See http://bit.ly/ghQqKX for the cover art.

This book has sold 300,000 copies (in a nation of 5 million), but it and others like it have also caused a bit of a ruckus, because the same word (“lort”) is widely used both for the bodily function and for the vulgar expletive. It’s caused some discussion about whether there should be a new national euphemism for pooping, to avoid a plague of toddlers running around burning their parents’ ears off.

That said, I scrolled through some other titles at publsishers’ and booksellers’ sites, but I didn’t see anything else even remotely offensive.

Also, as to why there are fewer Danish children’s books in translation, I think this is true for the arts in general relative to Sweden. I’m not sure exactly why. Maybe Sweden is just bigger and grander.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBe1KgrRYmU

Christopher, the author of the prize winning book you mention is actually by a German: Prof Werner Holzwarth. I would translate it as: “The little mole who wanted to find out who did their business on his head”. Kids LOVE this book, especially kids who are just learning to use the toilet. Coincidence? It seems that here in Europe authors aren’t afraid to tackle such issues.

Lisa, thanks – I think I knew that at one point. Danes are very matter of fact about these things, though. It’s okay to talk about the thing itself (because that’s what it is), but it’s kind of rude to use those same words in another context. You will also find very graphic nudity in Danish children’s books, come to think of it.

http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,493856,00.html

Another illustration of American squeamishness.:)

Wow, I’m astonished to see the interesting discussion my review, and mostly Zoe’s question, brought to light…

In fact the book is meant for kids, not for adults. True is that both in France and Spain, but as well in Germany and in some other northern European countries, there is a tendency to read tough stories to kids. In Italy (unluckily to my point of view) less similar books are published. There are many theories about why this happens and, to be honest, I do believe this would make a perfect subject for a whole tome… If we look back to traditional tales, to the Grimm brothers (for instance) we realise they were no sweet nor tender in their stories, nor were the traditional northern tales, nor Italian traditional tales. All these stories were, and in many countries still are, told to kids. I believe one of the questions we should ask ourselves is: why are we afraid of telling such stories to kids? Is it because kids are afraid of such tales, or is it because we are worried they might get upset? From my personal experience I tend to believe it’s more the second point. In fact, during the laboratories I do with kids, I have seen the same scheme reiterated many times: if kids are amid them, the majority seems to be adoring cruel and dark stories, they do enjoy the weirdest cruelties indeed but, if parents are around, they look back at their parents and start to show uneasiness. Now, a new question comes to mind: is it because kids are braver when in group? Or maybe they particularly resent their parents’ anxieties and they subsequently react differently than they would otherwise do? I would really like to know your thoughts about this! And, thanks to all for this exciting discussion and, if you wish, I shall bring new examples!

Cris

Thanks, everyone, for chiming in. Lisa, the last sentence of the article is striking: “So far, no other country has been overly concerned about the cartoon boobies and mini-penis, Berner said.” Not a one. We Americans are squeamish, yes?

Cris, I’d like to hear others chime in on your thoughts. I think I’ve made clear many, many times at the blog that I’m one of those parents who weigh in on the side of not-sheltering. The first time I heard The Great Sendak say (in a radio interview), “Children know the truth and they struggle with it and they despise you for giving them a sugar pill,” I think I did a fist pump + cheer.

Also, arguably, my favorite post ever was this one with fellow blogger and librarian Adrienne Furness, in which we address this. I love what she says about the version of The Three Little Pigs she chooses to read at her story times.

This has been very informative. Having not spent time in other cultures, I had no idea that the suppression of the shadow side was such an American phenomenon.

Very interesting points from all. I have a boy who is seven and who until recently got so upset with darkness/tension/conflict, particularly in movies, where the music contributes to the theme, that he cried and put his hands over his ears. And I’m talking Disney movies here. With books, though, he has a higher tolerance; in fact, I’d say it’s probably therapeutic at an appropriate level.

The mole video is hilarious. I love the end: if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em!

Jessica, it’s hard as parents, isn’t it? My grad school prof used to quote Maya Angelou, I think it was, who would say, let’s extend the innocence of our children, perhaps the antithesis here of striving to not shelter them. Or, who knows. Perhaps there’s a way to extend the innocence, particularly in today’s world, while also to avoid squeamishness on the Big Topics.

I’m probably just rambling here. But then parenting is the hardest thing I’ve ever attempted.

p.s. Thanks to Cris for starting a good conversation, though I guess we’ve steered away from Bluebeard. I hope Quarello knows how much we readers enjoy seeing his art here today.

Couldn’t join in any more yesterday what with sick kids but really enjoying the thought provoking exchange here. Yes, Quarello’s art is wonderful, not least because it gets us all thinking! And just because, here’s a link to Holzwarth’s blog

http://die-schoensten-kinderbuecher.blogspot.com/ (in German but with plenty of illustrations of books he’s enjoying)

This IS an enjoyable discussion inspired by Bluebeard. While compiling a list of my ten favorite books for Sergio Ruzzier (authour of Hey Rabbit), which by the way he hasn’t posted yet :(, I noticed that many of my favorites ARE my favorites because they deal with tough issues. When sharing these books with kids I sense (or imagine?) that kids are grateful for authors having enough respect in them to believe they can handle these issues and even that these books HELP them deal with the tough stuff in life. One of those authors is Chen Jianghong who wrote Le cheval magique which translates to The Tiger Prince. Well worth checking out.

Sorry, I goofed but then again I can’t speak french.So to set you straight the original title is Le Prince Tigre. 🙂

Great post. I love the illustrations.

Well guys, THANK YOU EVERYONE for this wonderful discussion, I thoroughly enjoyed it. In fact, I enjoyed it soooo much I’m thinking of bringing some more examples eventually… Well, of course if Jules agrees with me. It is so interesting to understand what is troublesome to other cultures… really!

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed the illustrations… soon more to come from Maurizio!

P.S. I LOVE Le Prince Tigre!!!

What makes me squirmy in children’s books? To be honest, dead parents. My girls are both still young, so it’s when they reach the point of being able to associate the storybook progression of “illness/old age –> death” with something that might happen in real life. It doesn’t keep me from reading anything to them (I don’t think), but it does remind me sometimes not to overstate my own illness or age. I don’t want to overstate it, because it’s a short phase, but I try to be respectful of their anxieties.

Also, religion.

[…] I have already discussed Maurizio Quarello’s books here and here and, from what I’ve told you, I am sure my personal admiration for this artist from Piedmont […]

[…] Zabala in February and Italian illustrator Maurizio Quarello in May. In January she discussed Barbe Bleue by Charles Perrault, illustrated by Maurizio Quarello, which led to a good discussion (in the comments) about whether or not we Americans are too […]