Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlight #5:

An Interview with Spanish Illustrator, Javier Zabala

February 24th, 2011 by jules

February 24th, 2011 by jules

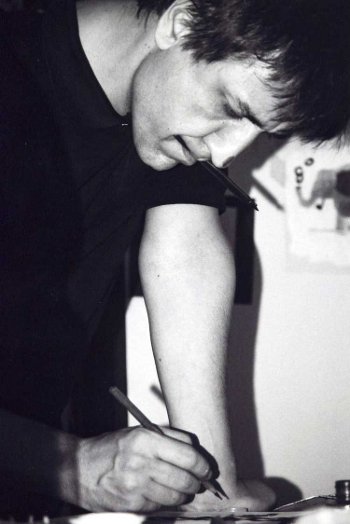

Jules: It’s time to welcome again the very smart Italian blogger with kickin’-good taste, Cristiana Clerici (pictured here), for another spotlight on international illustration. Today, she’s interviewing Spanish illustrator Javier Zabala, who talks about his work, his teaching, how his mother’s impromptu drawing competition when he was a child led to his career as an illustrator, what having courage means when working in the field, what it means to work “open-heartedly,” and much, much more. As always, I love that Cris stops by here to show me and 7-Imp readers what is happening in contemporary picture books over in Europe. To get the low-down on what I’m calling Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlights, visit this page of the site. I thank her kindly for contributing today. I shall kick back with my coffee and take in their conversation. (And I would like to know if Javier’s ever been told he looks like Nathan Fillion, but see why it’s better for Cris to be in charge of these interviews?)

Jules: It’s time to welcome again the very smart Italian blogger with kickin’-good taste, Cristiana Clerici (pictured here), for another spotlight on international illustration. Today, she’s interviewing Spanish illustrator Javier Zabala, who talks about his work, his teaching, how his mother’s impromptu drawing competition when he was a child led to his career as an illustrator, what having courage means when working in the field, what it means to work “open-heartedly,” and much, much more. As always, I love that Cris stops by here to show me and 7-Imp readers what is happening in contemporary picture books over in Europe. To get the low-down on what I’m calling Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlights, visit this page of the site. I thank her kindly for contributing today. I shall kick back with my coffee and take in their conversation. (And I would like to know if Javier’s ever been told he looks like Nathan Fillion, but see why it’s better for Cris to be in charge of these interviews?)

Without further ado, here is Cris. Enjoy.

Cris: Complete with mischievous glances and easy-going conversations, often enriched by the expression “hombre,” Javier Zabala embodies all the Spanish pleasantness and the professionalism that only a great artist has when it’s time to open up to others — with humility and generosity.

Cris: Complete with mischievous glances and easy-going conversations, often enriched by the expression “hombre,” Javier Zabala embodies all the Spanish pleasantness and the professionalism that only a great artist has when it’s time to open up to others — with humility and generosity.

I met Javier in Macerata, during one of the courses he does with Ars In Fabula — Fabbrica delle Favole, where I was allowed to observe him at work with his students. What mostly struck me about him is the mixture of empathy and severity he keeps during his classes, as much as in his private life he wisely mixes sensitivity and humor, shyness and gushiness.

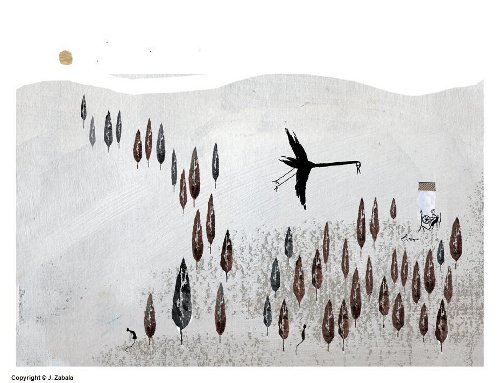

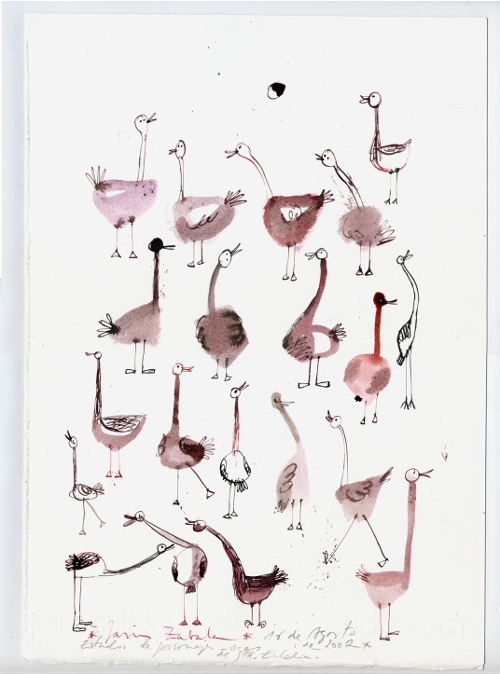

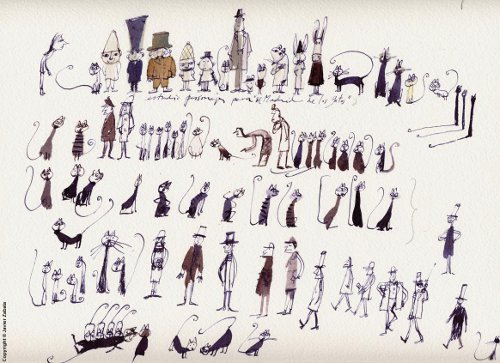

These qualities shine through in his artwork as well, with all its little curious references, its wisely-balanced colours, its characters sketched in his peculiar style, and those atmospheres so frankly masculine that filter through his tables.

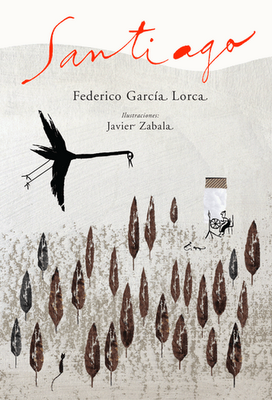

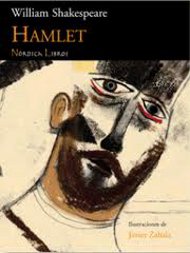

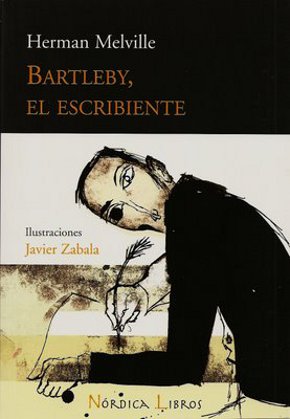

During his brilliant career as an illustrator, Javier has undertaken undoubtedly complex works: from the illustrations of Don Quixote, to those for Santiago by García Lorca (for whom he obtained the Mention of Honour at the Bologna Book Fair), to the illustration of Shakespeare’s Hamlet for adults. Amongst others, he has illustrated stories by Melville and Rodari. Let’s say he’s made sure to cover almost all possible experiences! He probably doesn’t have much hesitation when it’s time to take up new challenges; this is an attitude I personally appreciate very much, because it’s symptomatic of a strong will to keep evolving, researching, and studying, something a professional, in my humble opinion, should never abandon. Though united by a thread that resides in his sensitivity, his vision of the world, and in the ability with which he gets to transfer those into images, adapting the language according to the audience he’s addressing, all his books are different.

In his tables, where the mixture of elements deriving from cultivated references and personal experience is clear, the Spanish artist gives voice and expression to a pictorial language with avant-garde connotations, which is rich with fascination.

Well, time for the interview! Today I have the pleasure to be with one of the masters of illustration, who was born in Léon, Spain — Javier Zabala.

Hi, Javier.

Javier: Hola, buenos dias, ciao.

Cris: I shall first ask you a question which is maybe unusual: I would like to know if there is a place you prefer in your hometown, and which is it?

Javier: Without any doubt, the place I prefer in my hometown is La Colegiata de San Isidoro. It’s a Romanic church, wonderful, with amazing frescoes. This is where I used to play when I was a child: I remember that, after having been at the cinema with my brothers to see some movie about Romans, we enjoyed running up and down the twelfth-century walls that are close by. So, this is the place I prefer from my place of birth.

Cris: When you were a child, were you a reader. Did you enjoy reading? Were there books you liked most, or did you already prefer to draw?

Javier: I, just like all my brothers, used to read quite a lot, even though I wasn’t the one who used to read more. My older brother was. I remember my mother, more than my father, used to read a lot; therefore, my house was always crowded with books. As regards drawing, I have a very clear memory on how I began. In fact, I started to draw once we went on holiday on the north of Spain, by the sea. The weather up there was always quite awful and, in order to entertain us, my mother used to invent games for the six of us. To be true, we were six brothers, plus a number of other children. As it kept raining, one day my mother invented a drawing competition. I remember very well that day: I spent the whole day fishing with my cousin. When we got back, I asked him: “Have you prepared anything for the competition?” and he replied: “No, I’ve done nothing.” But he was lying, because when we got home he showed a beautiful drawing, fully-coloured. Of course, he won the first prize. There were many prizes, not just one, but I still remember that one prize he got for colours: I grew very upset with him, because he had lied to me. The following day I started to draw, and I’ve never stopped since then. I remember I drew an Egyptian army with wax pastels, and my mother gave me a prize as well. I bet it was to encourage me.

Cris: Can we then affirm that your drive to illustration originated from a challenge? And, during your professional career, you have been afforded many challenges: Besides the beautiful picture books you have done, I’m thinking of your works on poetry and classic theatre, such as with Shakespeare. We’re talking important challenges here, as it’s not easy to illustrate a poem (I’m referring to Santiago by García Lorca) or a classic like Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Javier: Yes, in fact, illustrating a classic is never easy, because it has already been illustrated many times, and every artist has its own reference or more than one reference. To be honest, though, I have to admit I like illustrating poems. I’m thinking of Santiago by Lorca, for instance, because poetry is an extremely free literary concept. You can do almost anything while illustrating. With Rodari, it’s likewise: I like Rodari, because his texts are very open, and this gives you the opportunity to express all your world in his works.

Going back to Santiago, I remember it was quite difficult at the beginning. When I started the project, I couldn’t find the right approach. At first, I tried approaching the poem starting with the South of Spain — Granada, specifically, where Lorca used to live. But this gave me no emotion, as it wasn’t my country: If you take a look at Léon [Javier’s hometown] and Granada, it looks as if they were two completely different countries. This is why I had to abandon this first attempt. I then tried with La Residencia de Estudiantes: This was the place where Dalì, Buñuel, and Lorca (Lorca and Dalì were roommates, and they used to organise parties; it was quite a common way of living and studying at those times in Spain) used to paint all together. These were the times of Surrealism. In those years, Lorca did many drawings; therefore, I had decided to try this way and approach a bit of Lorca’s aesthetics, but I was not able to get to a suitable result this way. From this second approach, all that remained is a little moon he drew: it was a tiny and narrow moon slice with an eye in the forehead, a lovely drawing you can see in the book.

In the end, I found the right way to illustrate Santiago, when I looked back at my own life: In fact, I was born in the middle of the Road to Santiago. My home town is right here, and I’ve seen people covering the road to Santiago my whole life. I did it as well, and many of the experiences in the book were my own when I did cover my road.

(Click to enlarge)

For instance, the cows have nothing to do with the text. It’s the cows I saw when, after having covered thirty kilometres, I was very hungry. In those moments, having lunch, pretty much like almost any other thing you do when you walk to Santiago, became a sort of Medieval experience: During the walk, everything is on a human scale. What you could afford with your own feet happened and nothing more than that. In the end, you despise the cars you meet along the road from time to time. It’s a very interesting experience that I was able to use for the book—by transferring into my illustrations a whole lot of small symbols from the road and from my personal life—and I believe I was able to obtain an honest book.

(Click to enlarge)

For Hamlet, it was different: I had no personal reference I could use, but I’m a bit of a kamikaze, and I didn’t think too much when I received the proposal to do this book. To be honest, I believe that, if you are honest and, most of all, if you let yourself go, then everything is fulfilled in the end, because you can’t avoid giving a personal interpretation. It can be more or less good, but it’s still your vision. I remember that in this book it was the pictorial technique I use, monotype, that showed me the way, and then I just had to let go. I’ve always liked the idea of illustrating books for adults, and this is something that at present you can do in Spain.

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: In fact, what is interesting is that the way you started with Hamlet is devoted to adults. Does this leave you more freedom from the expressive point-of-view, or do you believe that expressive freedom is independent from the public you’re addressing your work to?

Javier: It might be that, in a book for adults, you have a bit more of expressive freedom, because there is nothing you can’t illustrate: For instance, you can depict a scene where a man is killed without many problems—and in a noir novel, you can draw a man in the act of smoking or drinking—though I am convinced that, even when illustrating for children, you can do what you wish, and this is what I have done up to now. I know that this requires some courage: you need courage to go beyond limits or to anticipate or to dribble the market. You should always be aware of the fact that maybe what you propose will not be accepted, but in the end this is our job: we have to always walk a bit forward. You can’t keep repeating the same things you already did in the past. This requires courage — not the big courage a surgeon has when he touches somebody’s heart, but researching is the way illustrators have to show their own courage.

(Click each to enlarge)

Cris: Though, having courage implies as well that you have to show others something about yourself you usually don’t let shine through, right? If so, does this require even more courage?

Javier: In fact, this is true. I always say that an artist, if he wants to become a professional, must cut all those over-layers that society, school, mothers, grandmothers throw over you after a certain age, when you are more or less six or seven and you start your way into socializing, when you start approaching others. This is what happens in school, isn’t it? An artist then is an individual that, at a certain moment in life, gets free from those layers deriving from imposed experiences. Every layer must be cut open to be able to work open-heartedly. I’ve always believed that the work of an artist is necessary to protect all that is vulnerable and precious for individuals — but vulnerable most of all because, when a book is published, it says it all.

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: Javier, I know your wonderful illustrations have been and still are exhibited in Mexico — and in Madrid. Can you tell us something about those events?

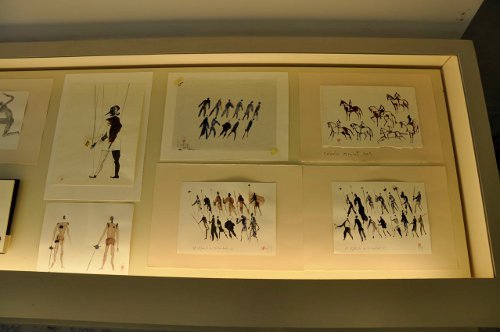

Javier: Yes, there were four exhibitions. The first one was called “La Villa del Libro” in Urueña, and it was quite a special exhibit, because it was almost completely formed by sketches showing how to start approaching a book subject. It was in a huge space — in a medieval village with many bookstores. This is why the show has been called “La Villa del Libro” [“the town of books”]. It ended on August 31st.

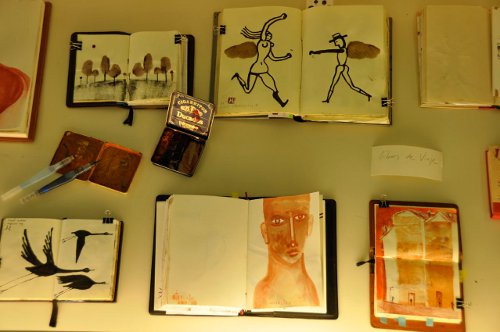

Then there was another exhibit in Madrid, organized by the Department of Beaux Arts in an historical library, called Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla. This one as well was quite a curious exhibition, because it was a retrospective and, furthermore, since the setting inside the library showcases antique books, the tables were located in crystal cases. There were twenty big illustrations. My idea was to reproduce my atelier [studio], to kind of move it over there.

(Click to enlarge)

The third exhibit was coordinated by the Fundacion Germán Sanchez Ruiperez. It’s a touring exhibition that was opened in September 2009 and that is touring Spain and the rest of the world. It arrived in Bilbao for the grand opening of the Cultural Centre Alhondiga; it’s a very important place. Together with my illustrations, there is a special exhibition with works by Rebecca D’Autremer as well. This show went to Mexico D.F. [Distrito Federal] in November and should get to Guadalajara as well. In Latin America, there has been another nice exhibition. This time it’s a collective, called Dibújame un Cuento [“draw me a tale”]. There were fifteen illustrators from Spain and Latin America. They’re all very interesting, except me! [Meanwhile, Cris adds, there was another exhibition in Macerata last December for the association Ars In Fabula].

Cris: You can’t say that, Javier. I don’t believe you! Listen, for those young illustrators who would like to learn through your experience, I know that during the summer you teach with the association Ars In Fabula. I would like to ask you about how you share your experience with students? What kind of course do you plan?

Javier: Every time I start a new course, and it’s a while I’ve been making them, I’m not really growing more afraid, but my respect for students grows constantly. There is now an increasing number of students whom have been part of my classes. Some have grown as illustrators; some, not. Usually students take lessons with many teachers, not just with me, and every teacher passes on his own methods. Of course, students take inspiration from this, though I believe they should then take a distance from it…

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: You mean that they should choose their own way?

Javier: Yes. It’s one thing to teach a technique; it’s another to pass on the technique together with a personal style. Those two parts are quite often connected, and it might be difficult to take a distance from them. This seems to me the hardest part when taking a course. If I think of it, I believe I would have enjoyed this a lot, at that same age, had I had the chance to receive all the information students can have today. In fact, what I usually try to do with them is to outline an historical route. I don’t simply talk about myself. I have heard students—god knows why in Italy it’s almost all female students at my classes—saying that in the first three days they were terribly afraid. They were saying it with detachment, because time had passed and they were happy: they had made marvellous progress, and I was astonished as much as they were. Of course, when you realize you’ve made progress, you calm down a bit, but it was curious to me learning that they were afraid at the beginning. It is true that the technique I teach, which is mixed media and pretty much a personal method, takes time to be absorbed: every student has to find his personal way to take in the procedure, and it’s true it’s not easy to start with it. At times, personal attitude is important as well: if you’re used to one graphic proposal, then you can obtain a more or less ordered series of tables, but the way I teach is a bit longer and harder to choose, though my experience is that when you find the right interpretation, then it’s much more satisfactory. Much depends on the single person. Maybe you should ask students.

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: I bet I already have the answer: I know you are a beloved and requested teacher. What else do you usually do during your classes, besides the study of your particular technique? Do you also work on story-boards or on the developing of an idea, on planning? Do students ever arrive with projects of their own and work on those?

Javier: At times, someone arrives with his/her own project, and this is what I prefer, because it seems to me it’s more useful for them, but it’s not so frequent. Here in Macerata there is also a specific course for this kind of work. Anyway, the developing of my lessons depends a lot on the kind of audience I have in front of me: I usually start by taking a look at their illustrations. It’s a bit of an intuitive task. Of course, there are always essential topics, such as story-board, for instance, because when working on a project it’s in the story-board that all eventual problems should be solved — though what really matters is to learn to work on the story-board, which is different. First of all, it’s a technical research; then you add all the elements, the events, the characters, and the rhythm of the book. This is the first practical act, and then it’s all about your personal sensitivity. At times, when their project isn’t clear enough and I ask for clarifications, students explain all the reasons for their choice, and my answer is that they can’t explain their reasons to every possible reader. In other words, if an illustration needs explanation, it means it’s not good enough.

At times it also happens that some students aren’t satisfied with what they have produced. This might depend upon the fact that they might not be in the right mood. The week they spend with me is usually very intense, and there is almost always a difficult moment. It usually happens on Wednesdays. On Monday, they start with joy, and they’re curious about their new teacher. We talk about everything and nothing, and we get to know each other a bit. Tuesday is the day when we start working seriously, as this is what we’re here for. On Wednesday, it’s when revision and discussion take place. And, after all, a productive crisis is unavoidable, and once it’s gone, there are always beautiful results.

Barcellona para ninos, Nordica Libros)

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: One very last question: Can you tell us something about your projects in the works, be those for kids or for adults?

Javier: At present, I’m working on about ten projects. Three are due pretty soon. They’re projects I’m doing with small Spanish and Italian publishers, but I can say nothing about them yet. I also have some adult books — one in particular that I really like, but again I can’t talk about it, because it’s based on a free text. All I can say is that it’s a wonderful project and that the publisher keeps calling me to know if I have finished it. I believe it will be ready for the Bologna Book Fair. I shall tell you more in person about this. And then I’m working on scenery for an opera. We have just started again, after a pause due to crisis.

Cris: Well, just to come full circle, we’re talking of another challenge here: from the illustrations of a tragedy, you’re now directly up to scenery. I’m impressed!

Javier: Yes, it’s fun if you think of how things start: Once, I had done a poster for an opera that took place at a Spanish theater and, after looking at it, they asked me why wouldn’t I make the scenery as well, and this is how we started talking about it. To be honest, I am not a set designer; therefore, I am supported by a team that helps me a lot. They’re very nice, and they tell me what can and what cannot be done. I have to admit I thoroughly enjoy doing the scenery; thus far, it has been a wonderful experience.

Cris: When will we be able to see it?

Javier: If everything goes according to our plans, it should be in September.

Cris: In a bit less than a year then.

Javier: This is it! It’s quite a long way, but it’s nice.

Cris: Javier, thank you very much for your time. I’m very happy I had the chance to talk to you, and I hope to hear from you soon with more news!

Javier: Whenever you want. Thanks to you.

(Click to enlarge)

Cris: What is your favorite word?

Javier: “Harmony.”

Cris: What is your least favorite word?

Javier: “Abulia.”

Cris: What turns you on creatively, spiritually or emotionally?

Javier: Sincere, genuine things.

Cris: What turns you off?

Javier: [The] routine, commonplace/cliché . . .

Cris: What is your favorite curse word?

Javier: “¡Joder!” (It’s obviously in Spanish…) [Cristiana: Now, with Javier I’ve had quite an exchange on this word, about how it should be translated… Javier says in Spanish it’s more or less like “prick,” and I have decided I trust him!]

Cris: What sound or noise do you love?

Javier: The crackling of fire, the noise of nib on paper… seagulls …

Cris: What sound or noise do you hate?

Javier: The noise produced by people gathering somewhere — in a soccer stadium, for instance, or during demonstrations on the street. The noise of soldier’s boots when they walk all together …

Cris: What profession other than your own would you like to attempt?

Javier: Musician, with no doubt.

Cris: What profession would you not like to do?

Javier: Oh, so many! Working in an office, at the bank…in an advertising agency …

Cris: If Heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?

Javier: “Good Lord, Javier! How come you’re here?” [laughing]

All images are copyright Javier Zabala and used with permission.

The spiffy and slightly sinister gentleman introducing the Pivot Questionnaire is Alfred, © 2009 Matt Phelan. Thanks to Matt, Alfred now lives permanently at 7-Imp and is always waiting to throw the Pivot Questionnaire at folks.

[…] Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast » Blog Archive » Cristiana Clerici’s International Spot… blaine.org/sevenimpossiblethings/?p=2083 – view page – cached Jules: It’s time to welcome again the very smart Italian blogger with kickin’-good taste, Cristiana Clerici (pictured here), for another spotlight on international illustration. Today, she’s interviewing Spanish illustrator Javier Zabala, who talks about his work, his teaching, how his mother’s impromptu drawing competition when he was a child led to his career as an illustrator, what… Read moreJules: It’s time to welcome again the very smart Italian blogger with kickin’-good taste, Cristiana Clerici (pictured here), for another spotlight on international illustration. Today, she’s interviewing Spanish illustrator Javier Zabala, who talks about his work, his teaching, how his mother’s impromptu drawing competition when he was a child led to his career as an illustrator, what having courage means when working in the field, what it means to work “open-heartedly,” and much, much more. As always, I love that Cris stops by here to show me and 7-Imp readers what is happening in contemporary picture books over in Europe. To get the low-down on what I’m calling Cristiana Clerici’s International Spotlights, visit this page of the site. I thank her kindly for contributing today. I shall kick back with my coffee and take in their conversation. (And I would like to know if Javier’s ever been told he looks like Nathan Fillion, but see why it’s better for Cris to be in charge of these interviews?) View page […]

Thanks for this wonderfully in-depth interview. I love how Javier started out drawing during a wet summer in Northern Spain. The Santiago illustrations are some of my favourites of his. Is the third exhibit still touring Europe?

Joanna

bravoooooooo my dear friend Javier 🙂

Morteza

Thoroughly enjoyed learning about Javier and his work. Gorgeous stuff. Thanks, both of you!

BTW, agree with Jules on the Nathan Fillion resemblance, which caused an early morning *SWOON*. 🙂

Joanna, sorry I haven’t gotten back to you. Yikes, I’m slow. I’ll ask Cris, and someone will get back to you.

Jama, I hope you survived your swoon.

This interview makes me want to:

— draw & paint all day long

— teach and read

— drink coffee, red wine too

— be outside. No, inside (in my studio). No, outside… inside………arrrrrrrggggghhhhhh –happy. Thank you!

What Rob said.

Hi to all of you! Sorry I’ve been silent, I have been working on soooo many things I forgot to check the page.

@Joanna: I believe the exhibit is on the way home by now, but I shall ask Javier soon, at present he’s busy working on a new book… more very soon on this!

@Jama: I hadn’t thought about his resemblance, I shall let him know, he’ll be pleased, by the way (as he said and I can confirm this) most of his students are female students… mmmmmmmh!! 😉

@Morteza: thank you!

@ Rob & Maral: well, thank you so much for your appreciation! I’m sure Javier is pleased as well! The truth is he did the most.

THANK YOU EVERYONE!

utterly fabulous in every sense.

[…] Found here […]

[…] Zabala is a wonderful illustrator who also teaches. In an interview in Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, he talks about the importance of the […]