A Visit with Hatem Aly

November 29th, 2016 by jules

November 29th, 2016 by jules

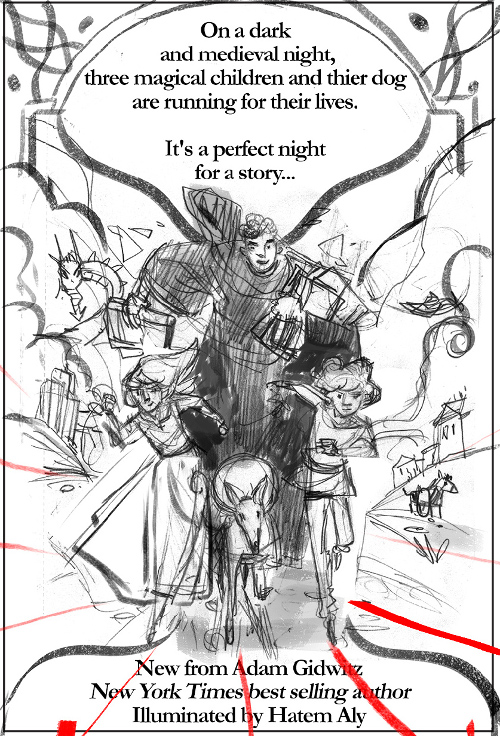

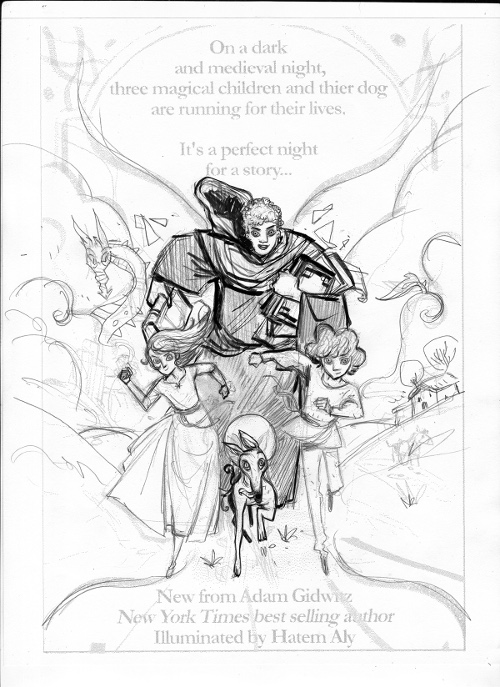

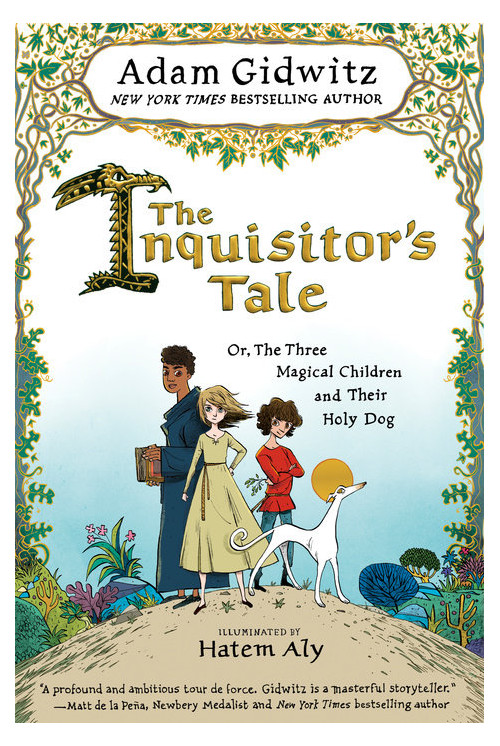

Because my family and I moved to a new house in the middle of this year and since moving is so time-consuming, it left a huge dent in my 2016 novel-reading. I’m trying to get caught up now on what I’ve read are some of the best middle-grade and YA novels of the year. However, one book I did read-aloud to my children, even in the midst of our move, was Adam Gidwitz’s The Inquisitor’s Tale: Or, the Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog (Dutton, September 2016), illuminated by Hatem Aly. And we all three enjoyed this tale of . . . well, I like best how it’s described at the New York Times, Soman Chainani calling it “equal parts swashbuckling epic, medieval morality play, religious polemic and bawdy burlesque.”

As you read above, the book is illuminated. That’s right. Illuminated, as medieval texts are. These images are from Hatem Aly, who visits 7-Imp today to share sketches and images and talk about this book. As Gidwitz says in the book’s opening:

Some of his illustrations will reflect the action, or the ideas, in the story. Some will be unrelated doodles, just as medieval illustrators often doodled in the margins of their books. There may even be drawings that contradict, or question, the text. That, too, was commonplace in medieval manuscripts. The author and the illuminator are unique individuals, with unique interpretations of the story, and of the meaning behind it.

This whole idea of an illuminated middle-grade novel could have fallen flat on its face. Spectacularly. But it works. And it’s unlike anything I’ve read in a long time. Adam describes Hatem as the “the best possible partner,” telling me that the Egyptian-born illustrator and comics artist was “so creative, really taking to heart my desire to have multiple perspectives on each page. I really wanted to recreate the experience of reading a medieval manuscript, with a central ‘authoritative’ text, and then commentary, disagreement, even play all around the margins. So there are spots where Hatem ‘disagrees’ with me, as well as places where flights of fancy take him somewhere totally different.”

I wanted to hear from Hatem about the experience — and see more of his art. I’m so glad he had a moment to chat, and I thank him for visiting today.

bbbzzz.jpg)

Jules: Can you talk about first reading Adam’s text and getting to work on your illuminations?

Hatem: The experience of reading it for the first time was extraordinary. As soon as I read the first chapter, I knew I wanted to work on it the best way I could. Wonderful story, great relatable characters, important subjects, and an interesting, intense plot and plot twists. Basically, a fascinating book. I was intrigued by the storytelling, beautifully-written, and yet how could I contribute to the book in a proper way? It was helpful from the start that the plan was to ‘illuminate’ the book in a way inspired by medieval manuscripts, so I had the form and did some research and started drawing. I was even listening to music from the era of the book to put me in the mood.

(Click to enlarge)

Once, I heard Maurice Sendak, one way or another, talk about the blending relationship between a story and the illustrations in a picture book as close, if not the same, as between words and melody in a song. He liked using music as a metaphor for everything, and I do agree with him. The Inquisitor’s Tale is not a picture book, but as I read it I had Mr. Sendak’s philosophy (if we might call it that) in my mind, and I thought, “How can I add some lovely tunes to this beautifully-written book?” So, I got it! It will be like a soundtrack to a movie (only in a visual equivalent) in the background — yet [it] gets to you and doesn’t distract you from the story. Adam Gidwitz is a wonderful storyteller, so for my part I didn’t worry about making the book beautiful as much as to make it look visually fun, interesting, and a bit mischievous. Reading books is a true joy, and not only was I hoping for people of all ages to have an amazing reading experience, but also [I wanted to] sneak my art into their memories of their favorite parts, or the ones that made them laugh, cry, or wonder. I hope the readers won’t mind me being so sneaky.

small.jpg)

use.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

(Click all but second to enlarge)

Jules: Needless to say, this is unusual — an illuminated middle-grade novel. Were you given freedom to illuminate as you saw fit?

Hatem: The illuminations were an emergence of my own vision and Adam’s notes, suggestions, and research as well. Add this to the insight from the editorial team, and I find it all harmonized beautifully. Freedom was given to me with some input to help whenever I need it. There were very natural and understandable limitations, given that the story is still historical and needs to be accurate at some elements. But, apart from that, it was smooth and enjoyable. I mean, how cool is it to be able to draw farting dragons and knights searching for a kid hiding in a dung heap?

use.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

(Click all but first to enlarge)

Jules: Seems pretty fun to me. Was it also as much as fun as it looks during the moments you strayed from the text altogether and drew some of the more nonsensical illustrations, what Adam calls “unrelated doodles”? (I love those moments.)

Hatem: It was so much fun! It also made sense! Surprisingly, I thought I would have to be [more conscious] of sneaking in some unrelated doodles here and there, but I found it happening organically. In fact, it was as if I had a glimpse of the motivations behind such old traditions of straying away from the text while illuminating. Who could resist adding a drunk turtle and a mouse riding a two-headed cat to their doodles anyway?

like he was a two-headed cat. …”

Jules: And the moments where you contradict and even question the text: Had you come up with any sort of rules (for lack of a better word) in your head for precisely when you’d choose to do that? Or did you just let the story guide you?

Hatem: I basically let the story guide me. And I had some inspiration from actual illuminated manuscripts to get a feel for how crazy they went with their visuals and to keep them relevant.

The only sort of ‘rule’ that Adam and I agreed upon is that there’s a difference between contradicting the text in a serious and interesting way and just drawing an inaccuracy. For instance, places and architecture style should be done mindfully, or it clearly tells a different or confusing narrative. I was trying to be systematically rebellious so that I wouldn’t confuse children — but still amuse them.

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: Adam suggested I ask about your only Christian friend as a child. What’s that story?

Hatem: Oh, that story gets me emotional. I told it to Adam, because it came back to me while reading The Inquisitor’s Tale.

Just a minor correction: He was not my only Christian friend. He was one of my friends, which included Muslims and Christians as well. He happened to be from a Christian family, and his name was Basim.

Miriam was immediately at his side. She put her arms around him. He was shivering.

She rubbed his thin shoulders. Jeanne spoke for Jacob,

saying what he needed to say but could not. …”

I believe it was first or second grade. We must’ve been seven years old. He told me: “I learnt today something strange!…” I asked him, “What was it?” He said: “That God died one day!” I said spontaneously: “What!? That is ridiculous! How could that even happen?” He got a little nervous. (He was not very good at school and was always self-conscious he was saying something wrong.) He said, “well, He came back to life again. It’s like nothing happened. It’s okay.” I said, “No it’s not okay! The world would vanish if that happened! How does God die anyway?” He answered reluctantly: “On a … cross? … That’s all I know.” I was puzzled, since I wasn’t familiar with the whole story or the visual reference of Jesus on a cross, but I know crosses are on the tops of churches. I failed to imagine it at this age. And it didn’t help that God to me, or as I had perceived, was not imaginable and didn’t have a specific form or location. I pictured a sort of an invisible light vanishing on the top of a church to make sense of the disturbingly incomplete story that I got from my friend. To me, it was like someone saying they caught a Wi-Fi signal and killed it with a knife. It was very weird to hear back then.

small.jpg)

slide backward away from him. Not smart.”

(Click to enlarge)

So, I went to my mom, asking, “What’s the deal with this?” She laughed and said different people have different stories about the same thing. We just have to listen to them and wonder. I was still a bit puzzled, but later on I connected the dots and got the idea of what was that all about.

A couple of years later, that kid disappeared and stopped coming to school. Three years later, I met his older brother and asked about him. “Where is Basim now? Did he change schools?” He told me that Basim died in a car accident a while back. My mom cried lots when I told her and still gets emotional when she remembers him and prays for him when he’s mentioned. My mother is very religious and she loved this kid, yet she is special. She views existence as a whole grand soul! She always told me to keep a plant and water it, because it prays for you. Animals do, too, and basically anything — that sort of sacred life or omnipresent bliss in everything in different styles. It’s apparent why this story stayed with me and left a little mark.

(Click second image to enlarge)

Jules: Well, bless my soul. And Basim’s, too.

What’s next for you? What new stories/books/comics will we see from you in the near future?

Hatem: I just finished illustrating a picture book and working on some other projects. Also, there is a work-in-progress graphic novel I am illustrating at the moment, called Asra and the Orphan Moon, written by Anne Sobel and Adam Sobel. It’s a sort of dystopian story about strong Arab women saving the world. It will be cool to see it finished!

(Click each to enlarge)

THE INQUISITOR’S TALE. Text copyright © 2016 Adam Gidwitz. Illustrations copyright © 2016 Hatem Aly. Illustrations and sketches reproduced by permission of Hatem Aly and the publisher, Dutton Children’s Books/Penguin Young Readers Group, New York.

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

small.jpg)

[…] Impossible Things has a terrific interview with Hatem Aly, illustrator of The Inquisitor’s […]