Seven Questions Over Breakfast with David Soman

January 31st, 2017 by jules

January 31st, 2017 by jules

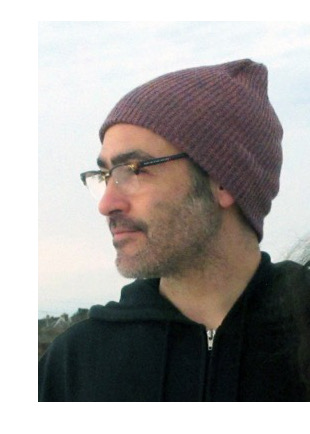

Author-illustrator David Soman visits 7-Imp this morning for a cyber breakfast and gives just the right answer to my question about what he would like to have on our cyber-table. “Coffee,” he says. “Coffee and blueberry banana pancakes. With coffee. Sweet Sue’s, a great breakfast joint in somewhat nearby Phoenecia, New York, calls blueberry banana pancakes ‘blue monkeys,’ which is what we call them at home. I love them on the weekends. With coffee. Did I mention coffee?”

Author-illustrator David Soman visits 7-Imp this morning for a cyber breakfast and gives just the right answer to my question about what he would like to have on our cyber-table. “Coffee,” he says. “Coffee and blueberry banana pancakes. With coffee. Sweet Sue’s, a great breakfast joint in somewhat nearby Phoenecia, New York, calls blueberry banana pancakes ‘blue monkeys,’ which is what we call them at home. I love them on the weekends. With coffee. Did I mention coffee?”

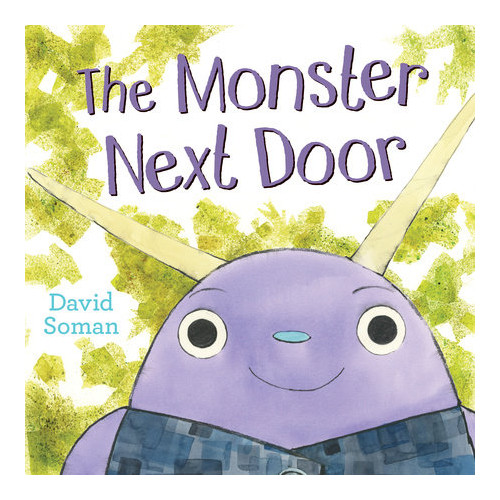

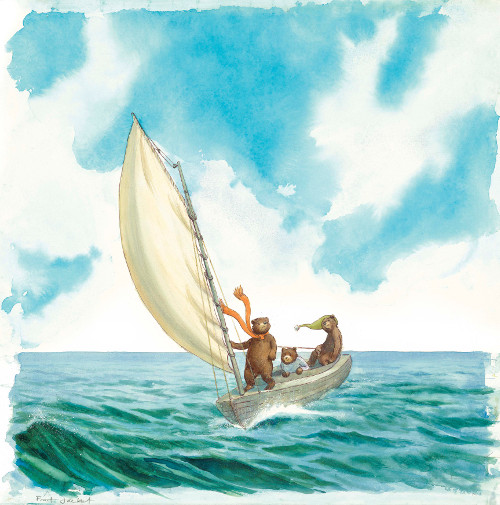

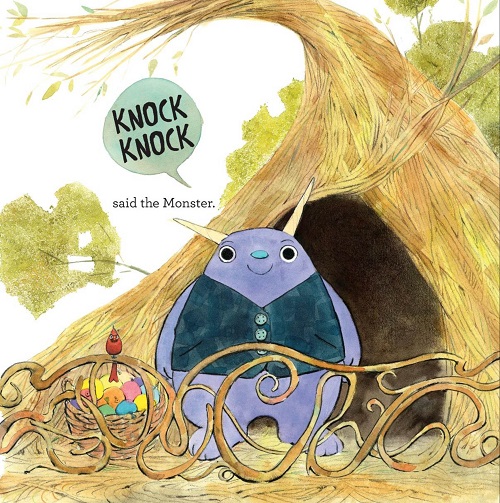

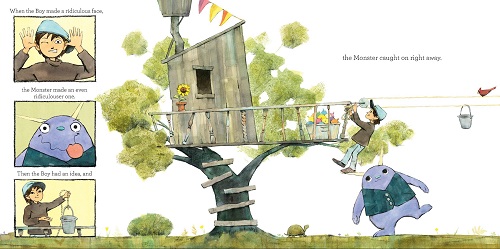

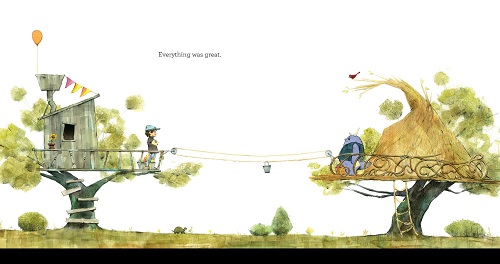

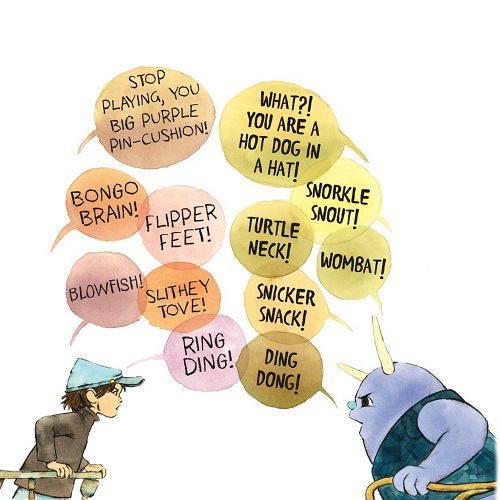

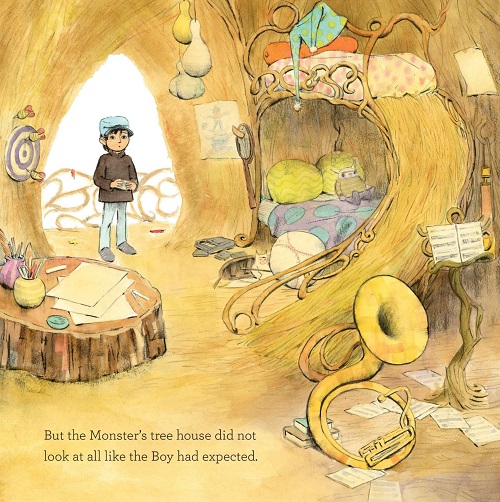

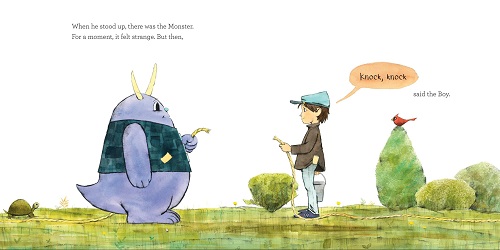

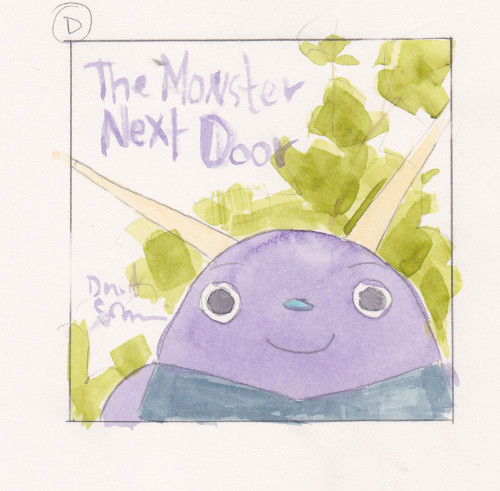

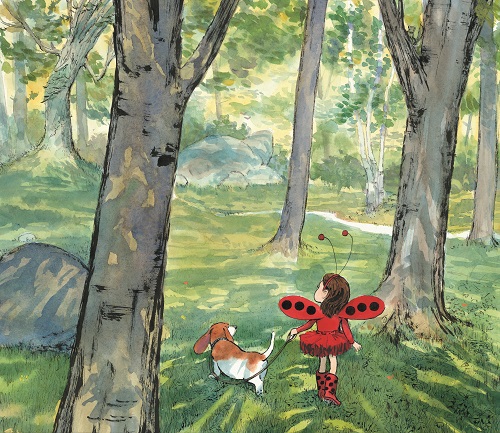

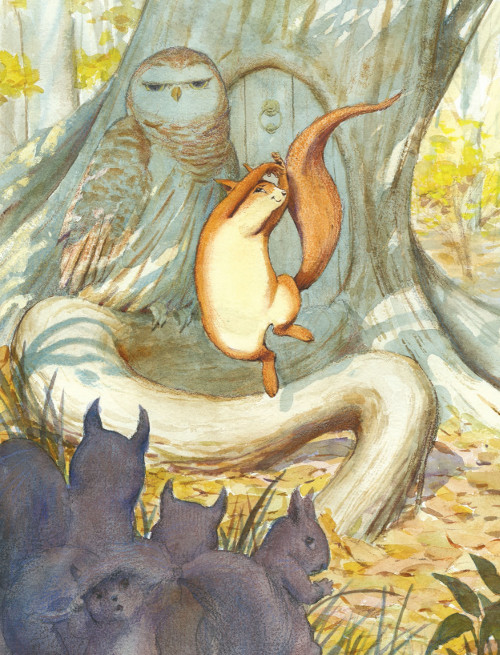

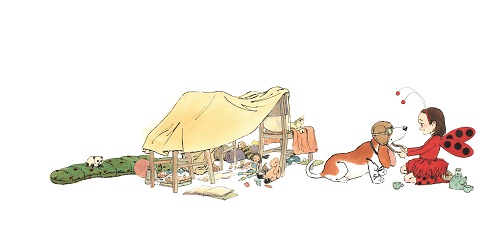

Coffee it is, and I’m pleased to say that David shares a whole bunch of art and preliminary images today. Pictured above is an illustration from last year’s The Monster Next Door, released by Dial in September. David both wrote and illustrated this one, though he’s most well-known for the series on which he collaborates with his wife, author Jacky Davis — the bestselling Ladybug Girl series. (If I’m counting correctly there have been over 20 sequels to the opener in the series, Ladybug Girl, published in 2008.) Let us also not forget 2014’s beautiful Three Bears in a Boat, one of my favorite picture books from that year.

But David’s first illustrated picture book, written by Angela Johnson, was published in 1989. He’s been making picture books for a while, in other words, and so it’s a pleasure to talk to him today about his work, his technique, his teaching, and much more. Let’s get to it, and I thank him for visiting today.

Jules: Are you an illustrator or author/illustrator?

David: Technically, I guess I am an author/illustrator, but in my heart of hearts, I still really think of myself as more of a visual artist. Which makes sense, as there’s really no comparison in terms of the amount of time that I put into each of these endeavors; it’s like 40 to 1 illustrator. Or more. Probably a lot more.

Jules: Can you list your books-to-date?

David: I’ve been a part of quite a few books, some that I’ve written and illustrated, some co-written and illustrated, and some that I only illustrated. A few of my favorites are:

- The Ladybug Girl Series (by Jacky Davis and myself)

- Three Bears in a Boat

- When I Am Old With You (by Angela Johnson — I actually did several books with Angela, and I love them all)

- The Key Into Winter (by Janet Anderson)

- And most recently, The Monster Next Door

Jules: What is your usual medium?

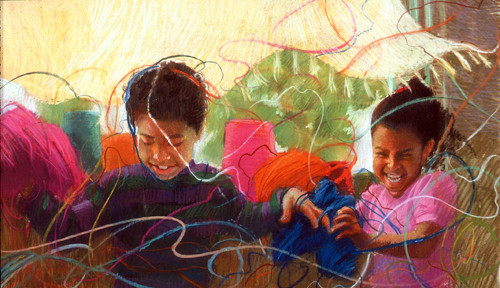

David: While I’ve worked in just about every 2D medium at some point, watercolors are by far the one that I have used most as an illustrator, though lately I have been combining it with pen and ink, colored pencils, and charcoal.

Jules: Where are your stompin’ grounds?

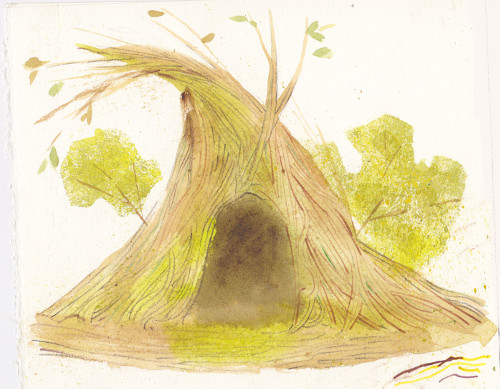

David: I live in the lovely, little town of Rosendale, here in New York’s Hudson Valley. It’s a really fun and funky place, filled with interesting shops and awesome people. Every now and again, we seem to be on the verge of being gentrified, but somehow we resist it. Fun fact: Rosendale is where they mined and made the cement for the Brooklyn Bridge, the base of the Statue of Liberty, and the U.S. Capitol building back in the 19th century. On account of that, we now have a lot of man-made caves hidden in the woods.

Jules: Can you briefly tell me about your road to publication?

David: I wish I could say that I was discovered as a handsome young artist, who did spectacular chalk drawings on the streets of New York, but here’s the real story: My stepfather is Max Ginsburg, who back in the late ’80s was one of the top paperback book cover illustrators working. At one point, as a side project, he did the jacket and interior pencil illustrations for Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, which brought him to the attention of none other than the great Richard Jackson, then an editor at Orchard Books. Dick wanted to hire him to illustrate a manuscript by a new writer (none other than the utterly brilliant Angela Johnson), and Max agreed — at least until he discovered that the pay for an entire picture book was the same as the pay for one (one!) Harlequin Romance cover.

Now, it just so happened that I had just arrived back in NYC (temporarily, I thought) from my summer job on Nantucket. Although I had not gone to art school, Max knew that I was a capable artist and said that he would introduce me to Dick if I wanted to do this job. I had loved drawing and reading my whole life, and so I lept at the chance (and thus spared Nantucket from any more of my “carpentry” skills). I went to meet Dick with a portfolio that—while including political cartoons from my college paper, paintings from classes in the Art Students League, and wooden masks I carved during a semester I did abroad in Bali, Indonesia—contained no proof whatsoever that I should be trusted to illustrate a 32-page picture book. For some reason, though, Dick hired me. Over the next year with his guidance—and that of a long list of other people, in particular my step-father Max and his good friends, Irwin Greenberg and Burt Silverman—I learned how to do paint and was able to illustrate my first book, Tell Me A Story, Mama [pictured immediately above].

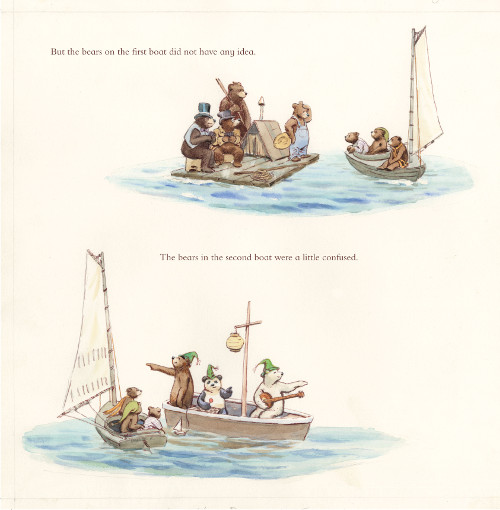

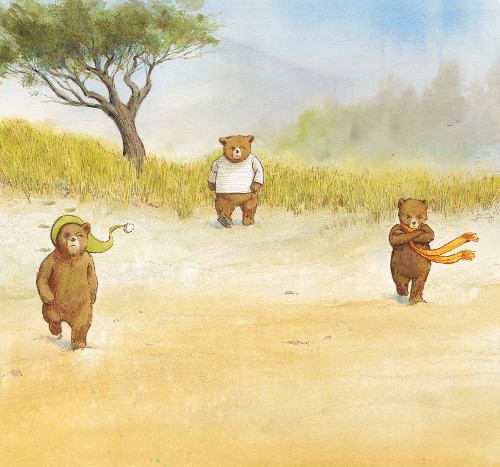

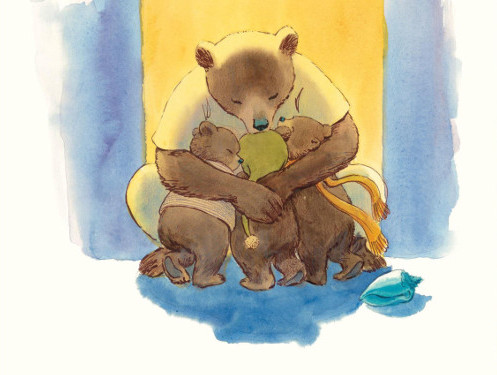

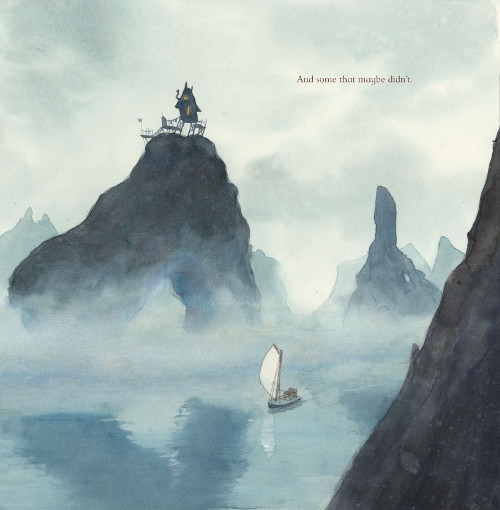

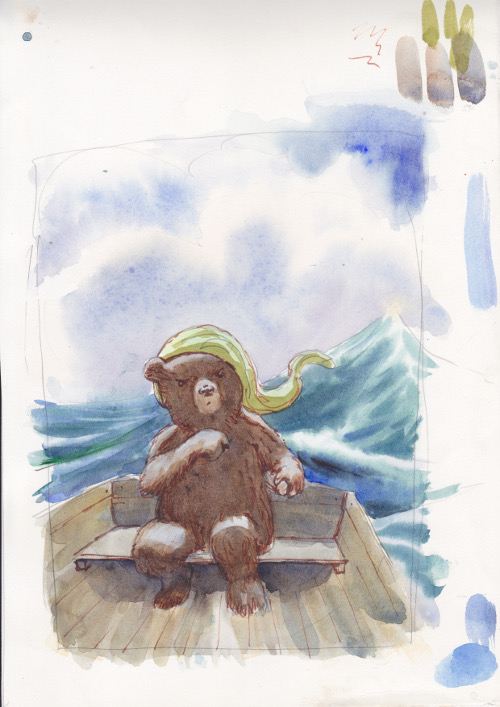

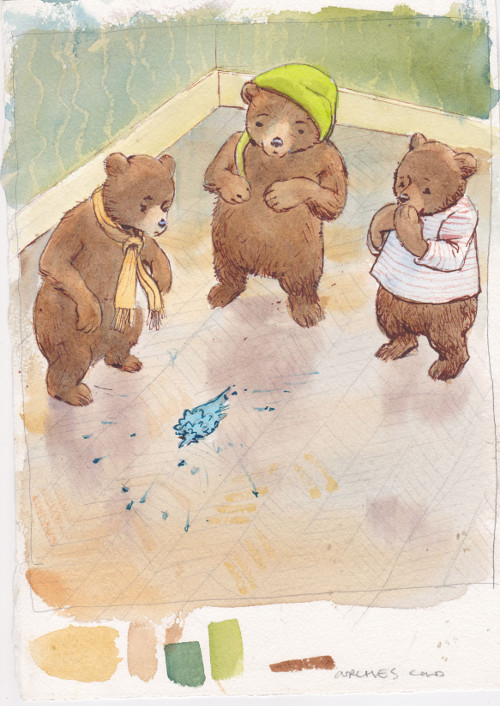

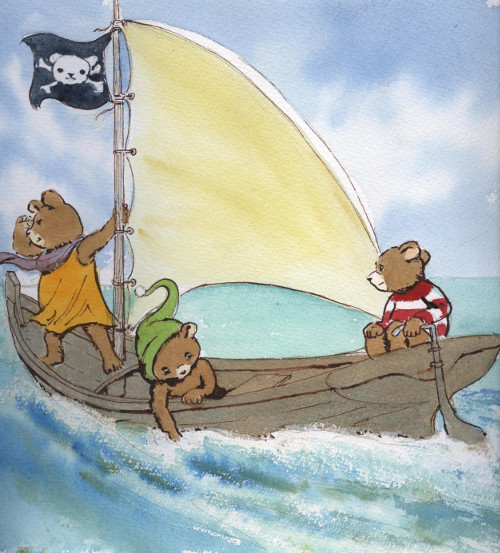

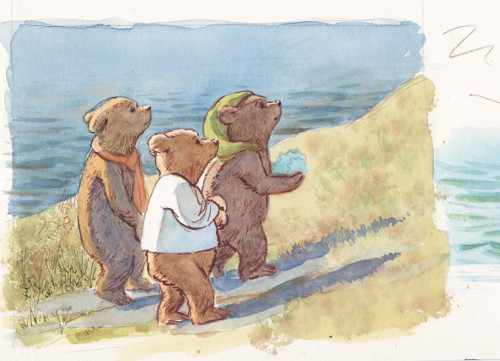

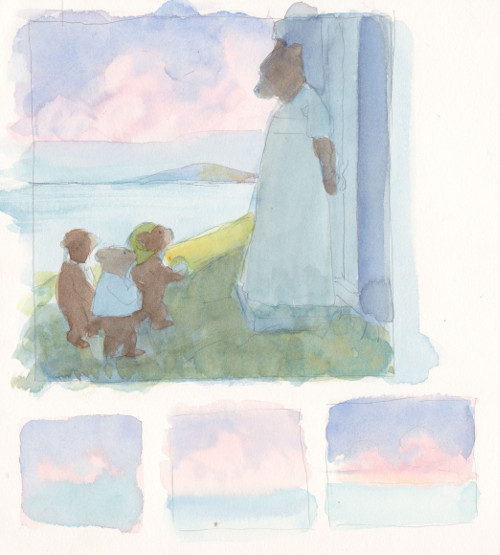

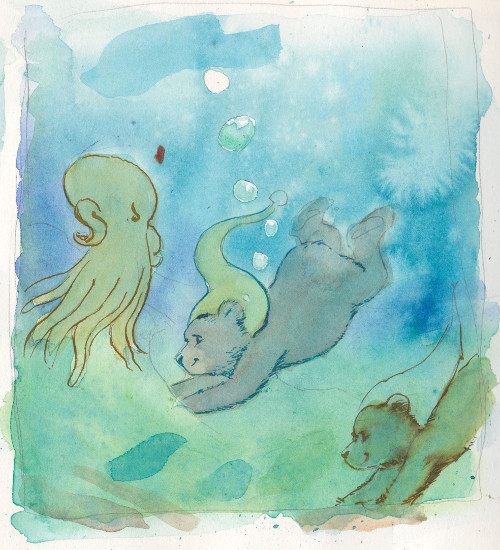

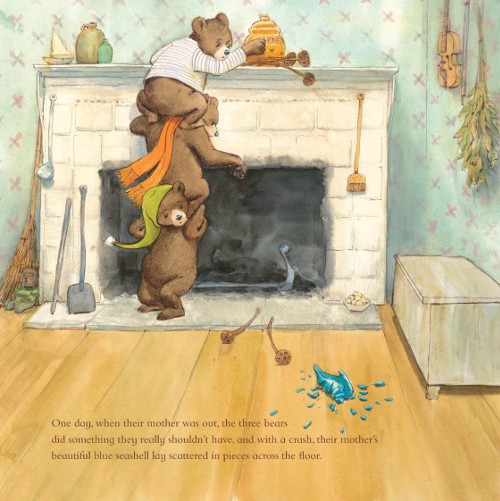

[Below here are some illustrations from Three Bears in a Boat, published by Dial in 2014.]

(Click to enlarge)

Dash, Charlie, and Theo, who lived by the sea.”

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

very squinty, very mad bear eyes, all the way back to their boat. …”

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

whose fault it was anymore, they were all in the same boat. …”

(Click to enlarge)

out of the storm and into the sun. …”

(Click to enlarge)

Then she brought them inside for a warm supper.”

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: Can you please point readers to your web site and/or blog?

David: Website? Blog? What are these?

Jules: If you do school visits, can you tell me what they’re like?

David: I love doing school visits. I actually think it might be the best job perk that comes with doing picture books for a living (that and working in your pajamas). While it’s true that I learn a lot about my work from the children’s reactions to it, the truth is I just find hanging out with them to be really fun — and funny. One of my favorite moments was when Jacky and I were doing a school visit for a group of about 300 kindergarteners and first-graders; as part of the presentation, we asked if they had any questions for us, and one little girl raised her hand and said “Could you tie my shoelaces?” So I did.

The visits themselves vary, depending on the size and age of the classes. While they can be more involved and creative if the group is small enough (I will help the kids make their own four-page stories), usually I read two books with a break in the middle to do some audience interactive drawing demonstrations. As I am a ham (and shameless), this can include some singing, posing, and lots of feedback from the audience, telling me when I get the number of polka dots wrong. Also, I reveal the secret of drawing a tutu. (Shhh. Don’t tell.)

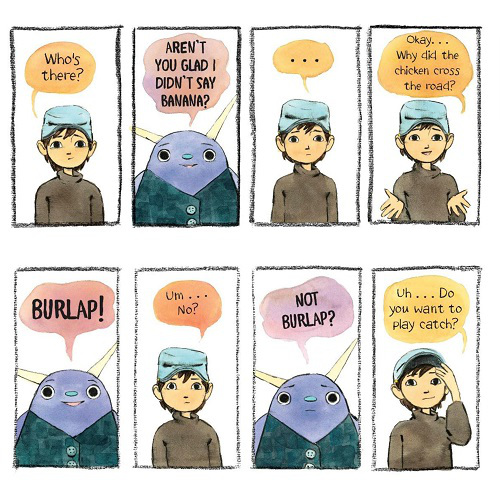

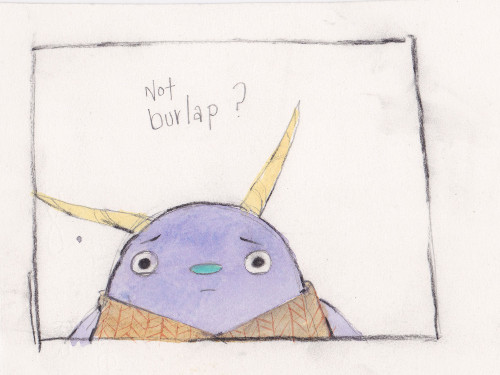

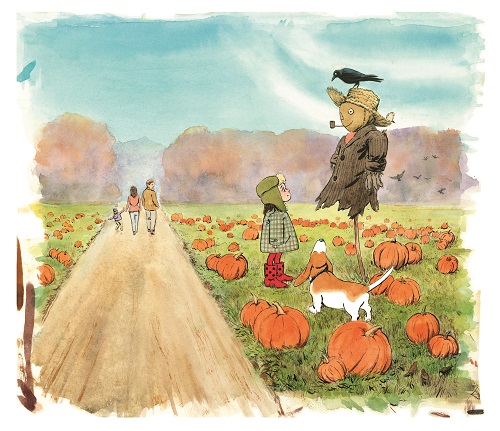

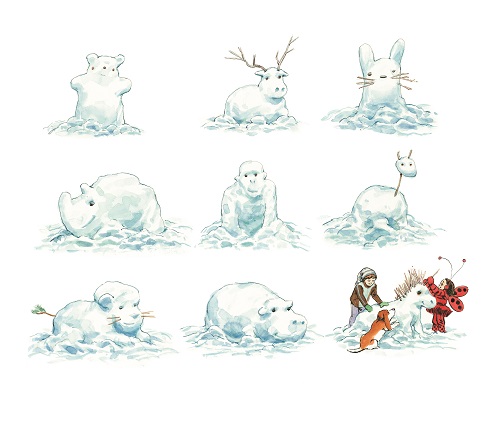

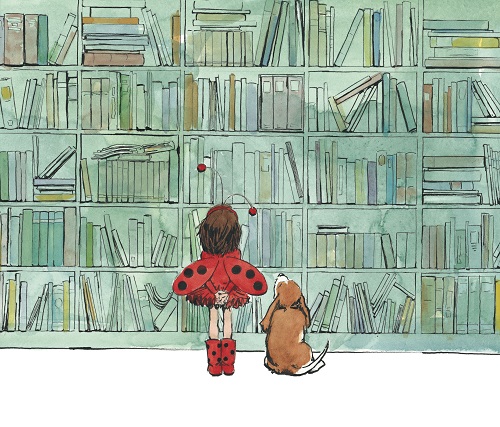

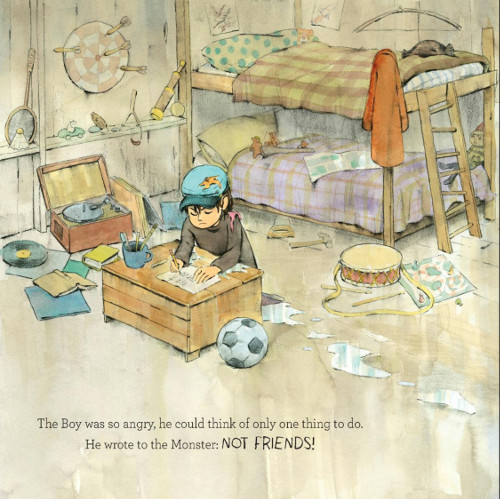

[Below here are some illustrations from The Monster Next Door, published by Dial in 2016.]

the Monster caught on right away.”

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: If you teach illustration, by chance, tell me how that influences your work as an illustrator.

David: Yes, I am an art teacher. I’ve been teaching in the illustration department at the School of Visual Arts for over twenty years, and the influence that teaching has had on my work has been tremendous. Though I did study drawing and painting at the Art Students League in New York (while I was in, or on vacation from, high school and college), I never formally studied art or illustration. So when I started working in picture books, I just sort of made it up as I went along. When I started teaching, however, I realized that if I wanted to convey information usefully, I had to think about my work in a more orderly way.

When I started doing this, I began to teach myself as much as I was teaching my students. But much more importantly, as part of class I would often bring in picture books that I loved, and in discussing why I thought these books were so fantastic, I began to really look at them not just as a lover of reading and art, but critically — in terms of how did they do that? In a lot of ways, I think that is where my education as a picture book-maker really began. And, of course, I also have learned an incredible amount from my students. For me, part of teaching art is recognizing that you aren’t teaching a subject that has one particular, definite way of approaching or doing the work, or a limited set of rules and methods. Rather, you’re there to help each student figure out who they are artistically — and to help them learn how to develop their work. You have to be open to their ideas, their creativity. This being the case, I’ve been exposed to so many more ways of thinking and working than I ever would have if I were not teaching. It’s been amazing. Some of these students are brilliant, and I have very much found my work influenced by what they have done themselves, as well as by the artists they’ve exposed me to. I owe them a lot.

(Click each to enlarge)

Jules: Any new titles/projects you might be working on now that you can tell me about?

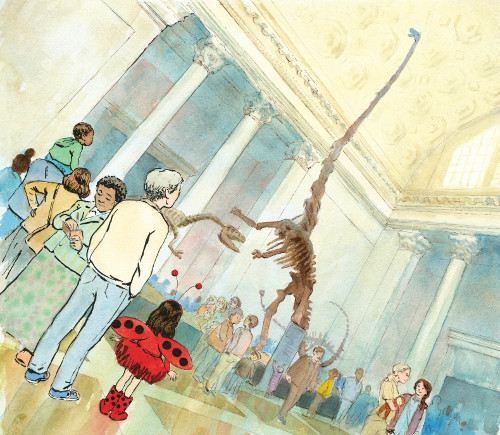

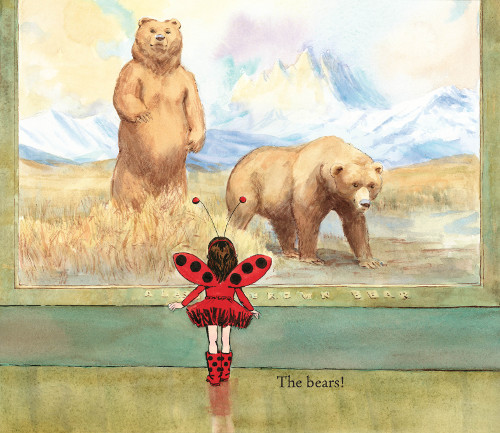

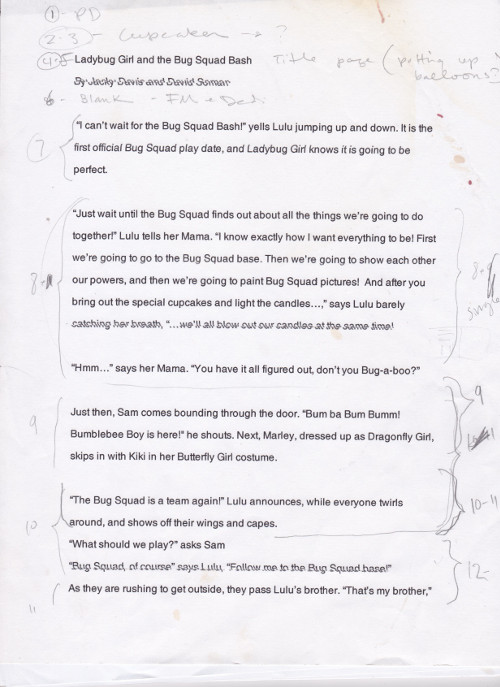

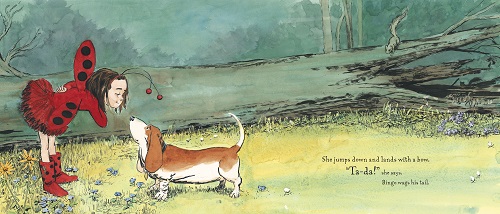

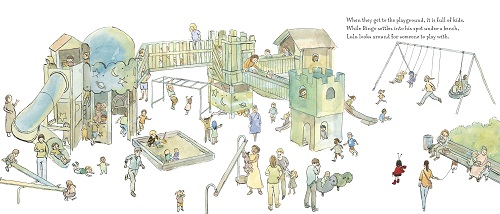

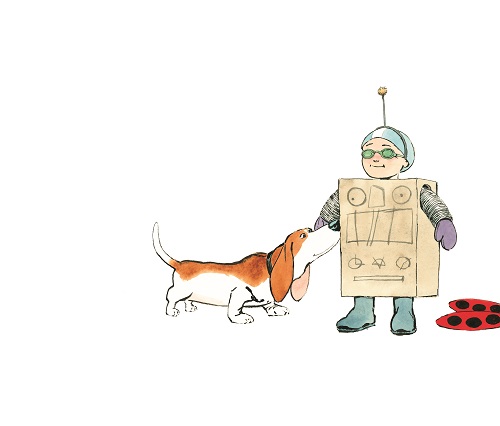

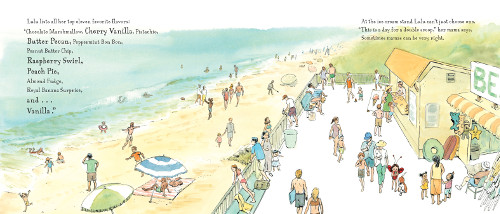

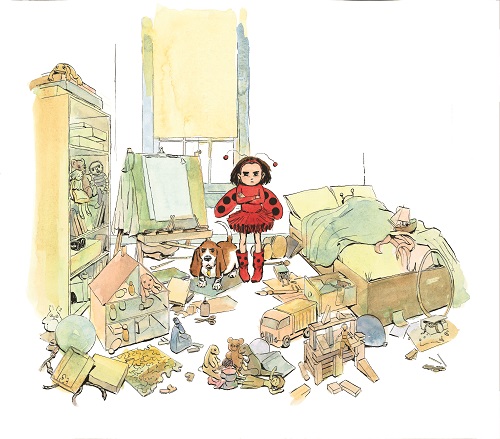

David: At the moment, Jacky (my wife and co-writer of The Ladybug Girl books) and I are writing Lulu’s next adventure, and I am in the color-proofing stage with the book we just finished, Ladybug Girl’s Day Out with Grandpa [pictured below], which allowed me to illustrate the American Museum of Natural History. This was an incredible experience for me, as I grew up across the street from the Museum and spent much of my childhood there. After that, I will be working on a new solo project. It’s going to be a sort-of counting book.

Okay, we’ve got our coffee, and it’s time to get a bit more detailed with six questions over breakfast. I thank David again for visiting 7-Imp.

Okay, we’ve got our coffee, and it’s time to get a bit more detailed with six questions over breakfast. I thank David again for visiting 7-Imp.

1. Jules: What exactly is your process when you are illustrating a book? You can start wherever you’d like when answering: getting initial ideas, starting to illustrate, or even what it’s like under deadline, etc. Do you outline a great deal of the book before you illustrate or just let your muse lead you on and see where you end up?

David: Okay, so my process …

Back when I began working as an illustrator, I did have a rather definite approach to each project. As I understood it, my job was to work with what I was given; the manuscript was somewhat sacred. It was important to me that I understood the text as the author had meant, and everything that I did was built on that. Of course, my own interpretations of characters and places were a big part of the books, too, but I think my concern with staying true to the author’s intent made me a little more formal in my approach.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Since I’ve begun to both write and illustrate my books, my way of working has become much more fluid, and I feel freer to allow changes to the written story to arise out of the process of drawing and doodling. The process for each book is a little different, but this back and forth between the writing and the artwork is really exciting. Also, as the writer of the book, the whole creative process begins differently — and, at times, unexpectedly.

For instance, Ladybug Girl began this way: For a while, Jacky and I had been talking about working together. We and our 2½-year-old daughter Lucy did a lot of sitting around together on the floor, and I would make doodles of Lucy while we played together. We would watch Lucy go about her day, and what really struck us was how much of her daily life was, to her, an adventure. That became something we wanted to explore in a book, but we weren’t sure how to put it together until one morning when Lucy came downstairs (dressed in wings, a tutu, and a pile of about six or seven hats), and Jacky looked at her and said, “Hello, Ladybug Girl.” That spark helped us combine what I wanted to draw with the story we wanted to tell. Of course, after that there was over a year of trying to write the story (and learn to work together!), while trying to discover what the art should look like. The character, the style of the art, and the story all evolved together (though I decided to lose the hats).

small.jpeg)

(Click each to enlarge)

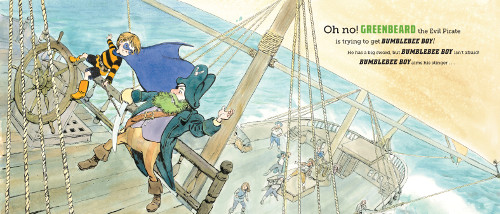

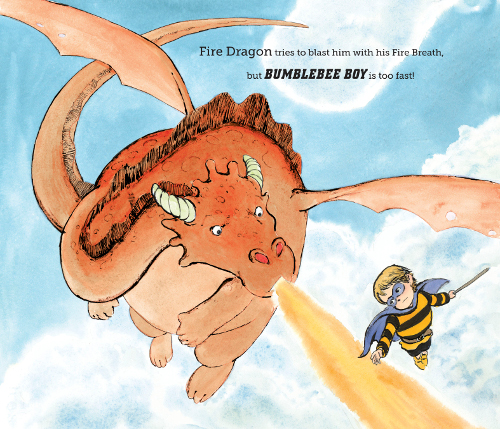

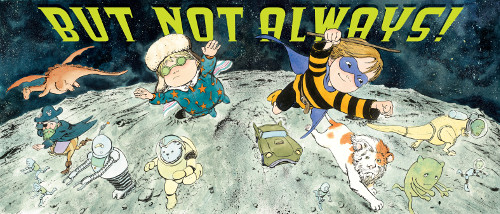

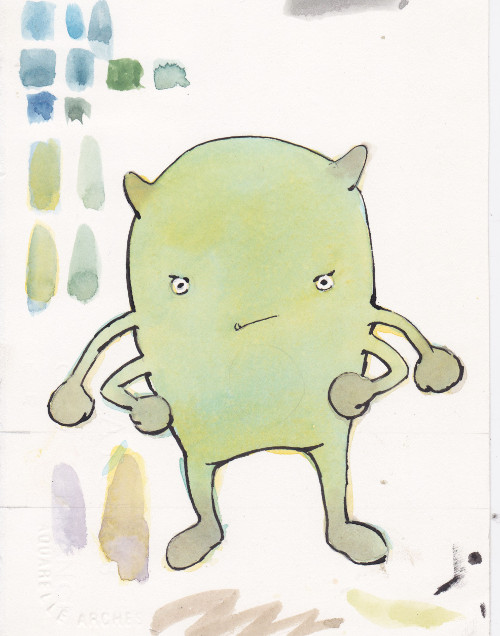

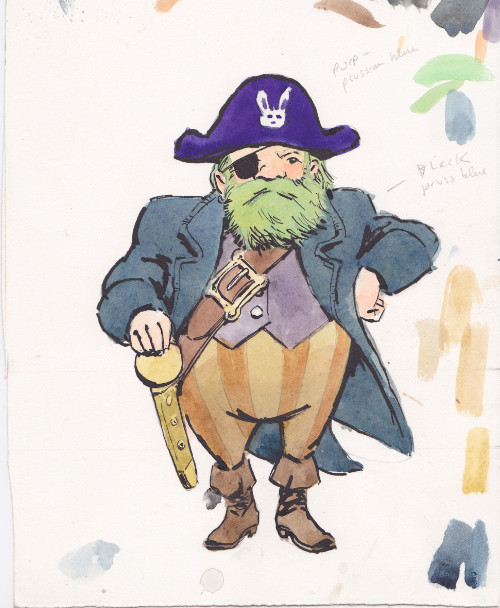

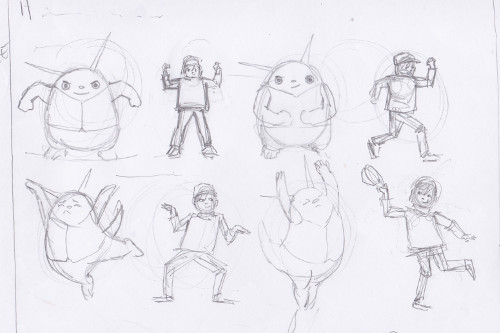

The Amazing Adventures of Bumblebee Boy was obviously a part of the Ladybug Girl world, so there was much less need to go through figuring out the style of the art. But even so, some interesting things popped up, and I had a really good time designing all of his imaginary opponents.

(Click each to enlarge)

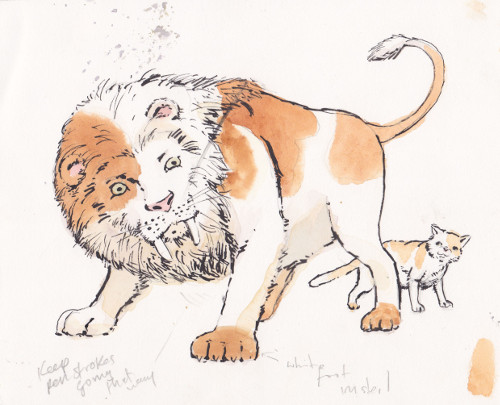

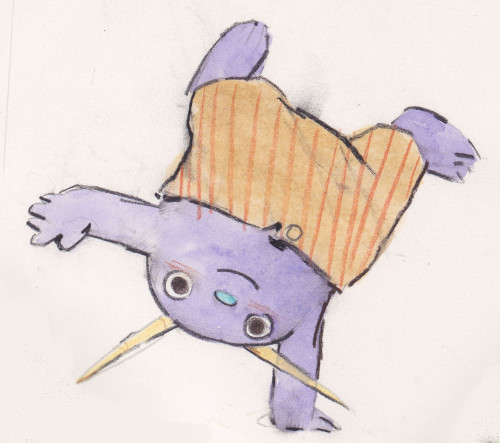

One, in particular, was a bit of an education in and of itself, The Story of Giganto:

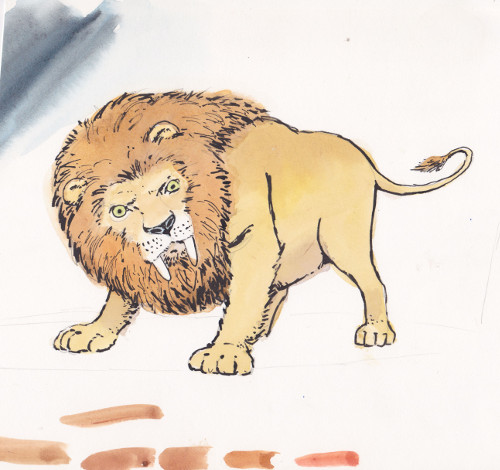

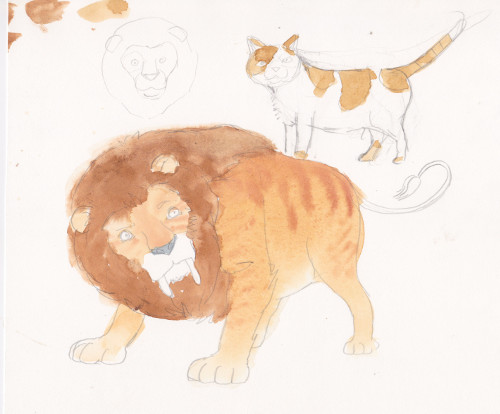

Sam (a.k.a. Bumblebee Boy) was imagining that his cat, Rhubarb, was a ferocious sabre-toothed lion (a.k.a. Giganto), and they were going to do battle.

I didn’t really know what Giganto would look like. He first time I drew him he came out like this:

After looking at what I had done, I was like, “No. No, no, no, no.” He was a bit too ferocious-looking. In trying to figure out where I had gone wrong, I realized “Duh! He’s supposed to be based on Bumblebee Boy’s cat, not on a lion! There’s the problem.” I then also realized that I had not yet figured out what I wanted the cat to look like. I have always liked the way tabby cats looked, so presto! Problem solved. Except that when I started to paint him this way …

… I realized I still had the same problem: He still looked too scary. How could I make a giant cat not too threatening — and yet tough enough for the story? Then, I remembered that we had stolen the name Rhubarb from our friends’ cat and that the actual Rhubarb was a calico, and so …

And there he was. The actual drawing hadn’t changed at all; he was still imposing, but the pattern made him seem really ridiculous. I think there may be a moral to this story, but I have no idea what it is.

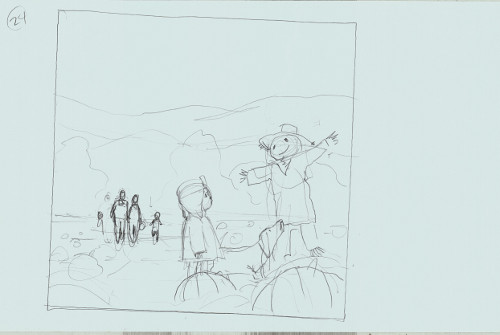

Three Bears in a Boat began with a dream that woke me up in the middle of the night. It included this image:

I felt compelled to figure out who these bears were and why they were in this boat, and I started writing the story at the kitchen table at about 3:00 in the morning. An interesting part of doing this early concept art, for me anyway, is that—no matter how clearly I think I know what I am going to do or what will happen when I sit down to work—I often have no idea what is going to come out.

A digression:

Making a book is a long and large endeavor (for me, anyway); it’s a lot like making a movie by yourself. And a big part of the experience of it is emotional and psychological. You get this idea, this trail you have to follow, and you begin to find yourself drawn into the world that you are creating. It’s very exciting, very energizing, and very necessary in order to make the story come alive. So you work and work, but the work is long, and often you run into blocks and dead ends. And that initial spark fades a little, and uncertainty and doubt creep in. You go from thinking “this is great, and so am I!” to “this is terrible, who am I kidding?” At this point there may be a lot of dark nights of the soul or funny panda videos on YouTube, but hey, we won’t judge. Happily, I have found that this stage passes (because you grit it out, or there is an inversion in the weather, or the muse smiles, or Jacky says, rightfully, “you go through this every time; you’ll be fine, sheesh!”), and you sit down to work and it feels like the sun is shining again.

I have an incredible Martha Graham quote in both my studio and in my classroom at SVA that helps me with this. I won’t quote the whole thing, but it says that artists shouldn’t judge themselves, that they should just keep on creating, and that:

There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open. …

It’s intense. (Of course it is. It’s Martha f-ing Graham!) And she was speaking about dance, but I find it helpful to recognize all creative people go through the same kind of emotional journeys while doing their work and have the same bouts of doubt and questioning.

The Monster Next Door was also its own process. There were some ideas I was wrestling with, but I found that as I worked, the Boy and the Monster had ideas of their own. They sort of hijacked the book. In some ways, the story was never really written. The book sort of evolved out of the drawings.

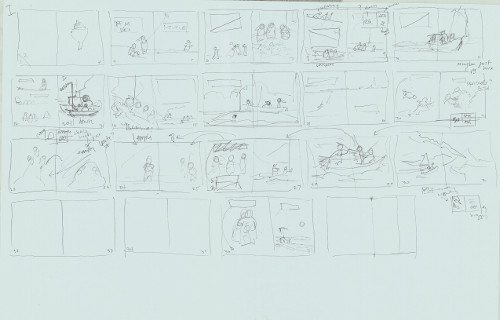

After I have the concept art and stories are done, I start trying to find the best way to tell the story in the picture book format (mostly I do 40-page books these days), and to do that I need to give myself a sort of overview of how it will all fit together. That means I spend a lot of time figuring out what scenes in the manuscript matter (which, in practice, means lots of scribbling and circling all over the type-written pages) and then drawing little picture maps of the book to help me see if everything is fitting together well. Here are some examples from Three Bears and Ladybug Girl and the Bug Squad:

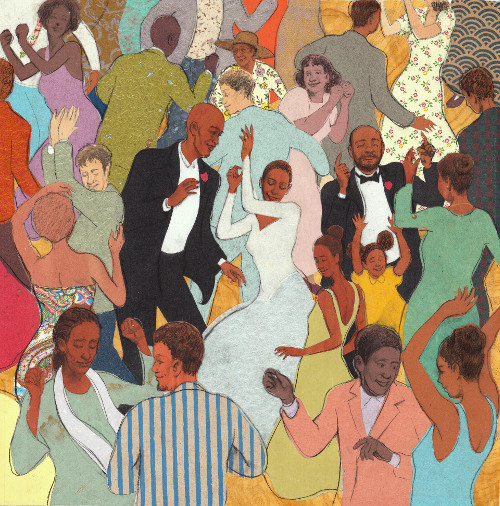

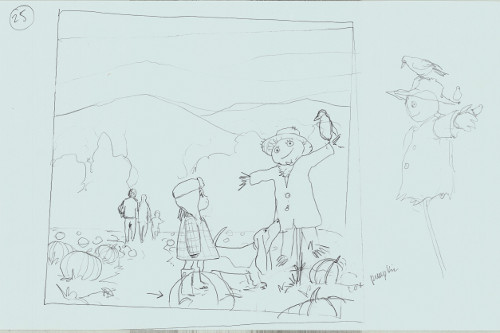

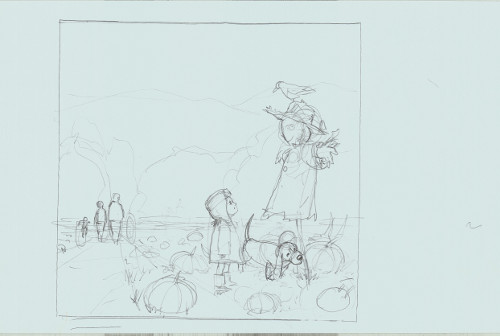

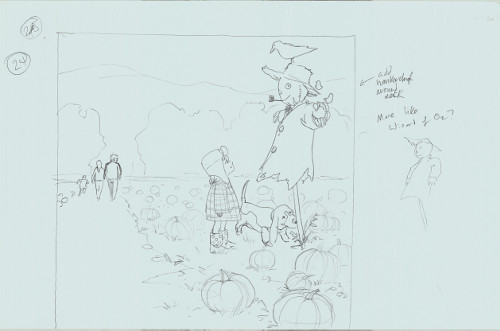

After that, I’ll get down to the nitty gritty of figuring out each page, which means everything from the overall composition, to the type placement, to the gestures and expressions. I do a lot of sketching and refining of the drawings and go through a lot of paper. I find it’s only when I am doing the drawings that I really begin to understand my books, and it is where I usually notice things that could be changed, whether by taking stuff out, adding stuff in, changing the writing — there’s a lot of discovery. It’s also really fun. I mean, I get to sit here and figure out what a dancing Monster or hula-hooping bear look like.

If you want the technical details, all my preparatory work is done in pencil. Once I have a firm idea of what the scene needs to contain and be about, I do a lot of thumbnails. Then I take the composition I like best and work at it. I work at the actual size of the book, and use my light box to trace and re-trace each drawing, refining and making changes along the way. (I read that Degas did that with his drawings and tracing paper, so you know, as they say, steal from the best!) Here is an example of making up one of the pages for Ladybug Girl and the Dress-Up Dilemma:

Then I put it all together with the type to make the dummy. The dummy is an amazing part of the process. It’s really the first time you get to see how your work works as a book. It is a good time to make a few—or a lot of—changes. When it’s finally all together, off it goes to my editor and art director.

And then it comes back, digitally these days, and with any varying amount of suggested changes, regarding anything from the pacing, to the compositions, to the type placement. Sometimes I agree with their notes; sometimes, not. We talk it through and try to come up with what we all agree will work best. Sometimes that has involved making more than one dummy.

Same pages in different dummies. I swear:

As for the final art, these days I do most of my work with watercolors and pen and ink, although colored pencils, charcoal, and gouache have all made their appearances. And Jasmin Rubero, Dial Book’s brilliant designer, has also helped me with some digital compositing and repairs. (There have been more than a few unsightly ink splotches all over the artwork that she has kept from the public’s view.) To do the finished art, I enlarge the image from the sketch dummy, refine the drawing, and then trace it onto watercolor paper — and get to work.

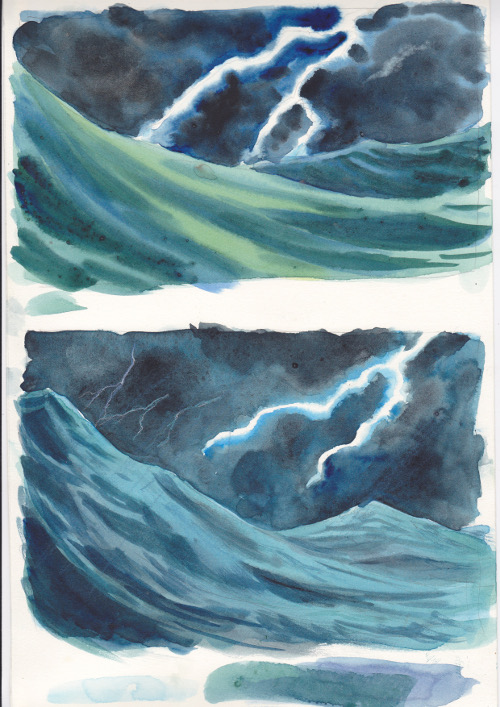

Working in watercolors is like working with a mysterious partner or performing live; it’s exciting, but you never quite know what’s going to happen. When I climb the hill to my studio, I am not sure if the picture I’m working on will take a couple hours or a couple days, or if it will be one take or work only after several failed attempts (which we’ll call “learning experiences”). I also do lots of color studies [pictured below], as it is so hard in watercolors to change anything once you begin painting. (I admit to being a little bit envious of those who work digitally.)

As a matter of fact, I have an Ikea bag under one of the tables in my studio that I fill up with all the mess-ups and studies and scraps from each book. When the art is finally accepted, I bring the bag to the dump to be recycled. Sort of a sage-burning kind of thing.

2. Jules: Describe your studio or usual work space.

David: After having several different studio spaces in places like the back of an industrial cabinet-making shop, a semi-rehabilitated t-shirt factory, a quasi-legal artists’ squat, the unused office of a Moroccan rug store (all of which were either unheated, un-air-conditioned, leaky, or all of the above), I finally built my own studio on a hill behind my house. The fact that I built it mostly myself—and that it is still standing—makes me impossibly happy. It is also a handy place for my daughter to have big sleep-over movie parties. Hence, the rolled up futon and spare mattresses.

3. Jules: As a book-lover, it interests me: What books or authors and/or illustrators influenced you as an early reader?

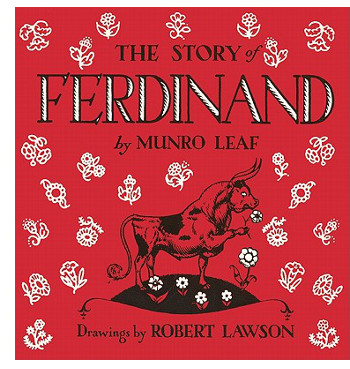

David: I really hate to make lists, because I know I am leaving so much out, but here are the picture books that most immediately spring to mind from my childhood: Go, Dog. Go!; Little Bear; The Story of Ferdinand; Richard Scarry’s What Do People Do All Day; The Snowy Day; The Cat in the Hat; Horton Hears a Who!; Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day; Caps For Sale; and a really cool book about dinosaurs back from when there was still such a thing as a brontosaurus. I can’t say how all these books may have influenced me (the way I can say that John Singer Sargent influenced my approach to watercolors), but all of these books—and more—are part of my DNA. I don’t think I would be who I am without them.

David: I really hate to make lists, because I know I am leaving so much out, but here are the picture books that most immediately spring to mind from my childhood: Go, Dog. Go!; Little Bear; The Story of Ferdinand; Richard Scarry’s What Do People Do All Day; The Snowy Day; The Cat in the Hat; Horton Hears a Who!; Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day; Caps For Sale; and a really cool book about dinosaurs back from when there was still such a thing as a brontosaurus. I can’t say how all these books may have influenced me (the way I can say that John Singer Sargent influenced my approach to watercolors), but all of these books—and more—are part of my DNA. I don’t think I would be who I am without them.

4. Jules: If you could have three (living) authors or illustrators—whom you have not yet met—over for coffee or a glass of rich, red wine, whom would you choose? (Some people cheat and list deceased authors/illustrators. I won’t tell.)

David: Can I preface this by saying many of the artists I admire most I have been lucky enough to meet. (So I can leave out Jon Klassen, Laurie Keller, Loren Long, Carson Ellis, Lane Smith, Jillian Tamaki, Ted and Betsy Lewin, among many others.) But even still, this is crazy hard to answer. Keeping it in the picture book family, I’d say: Lisbeth Zwerger, my biggest art crush, whose work takes my breath away; Shaun Tan, whose art shows me how far we can really go if we are unafraid of how much work it takes to get there; and Lauren Child, because: brilliant, wise, and so damn funny. So, yeah. Them. Could I get a bigger table next time?

(Click each to enlarge)

5. Jules: What is currently in rotation on your iPod or loaded in your CD player? Do you listen to music while you create books?

David: Good question!

While I listen to just about anything that isn’t death metal or show tunes, the truth is that music effects me so much that I have to be really careful about what I put on, depending upon where I am in my work. I find I write best when it’s quiet, otherwise the music takes me somewhere that I maybe don’t want to go (though trying to pick out the perfect music for what I am writing is a wonderful way of procrastinating — just sayin’). When I’m trying to layout a book, I like wordless music, so there is a good a mount of jazz: Coltrane, Miles, Monk, Mingus, and Django Reinhardt, as well as some ambient Brian Eno tracks and the occasional dip into Bach and Philip Glass.

When I’m drawing, any and everything could be playing. But in recent months, and depending on my mood, there’s been a lot of Andrew Bird, M. Ward, Chance the Rapper, FKA Twigs, Kendrick Lamar, Tom Rosenthal, Lou Reed, The Decemberists, movie soundtracks, Gillian Welch, Tom Waits, Johnny Cash (always and forever Johnny Cash), and Queen Bey herself. (Lemonade just gets better and better every time I listen to it.) I’ll admit: I’m a little eclectic.

But during the long, and at times lonely, workdays and nights of doing the finished art, I have found that I like listening to someone talk or tell me a story. So podcasts, recorded books, or the dulcet tones and mind-bendingly bad (though often amusing) calls of John Sterling, as he does the play by play for New York Yankees’ radio, are more often on than not.

David: “I was asked to contribute to Penguin’s A Celebration of Beatrix Potter, which came out in honor of her 150th year, and I was lucky enough to nab Squirrel Nutkin, one of my all-time favorite ne’er-do-wells. There is an incredible array of amazing illustrators who are sharing their different takes on Ms. Potter’s incredible universe of characters, and I am honored to be among them. (I’m in a book with Tommie dePaola! I’m in a book with Tommie dePaola! I’m in a book with Tommie dePaola!)”

(Click to enlarge image and see David’s text;

also see this previous 7-Imp post for more)

6. Jules: What’s one thing that most people don’t know about you?

David: Well, one thing that most people don’t know about me but that that I am willing to share is that there is a “David doll” in just about every book I’ve done since the mid ’90s. It began when my sister Liana (who is an amazing artist) and I were doing what we do, which is to say being somewhat ridiculous (or as our mother would put it “being idiots”) and drawing insulting cartoons of each other (wish I could say we were little kids, but this was in our 20s). She did one of me that was so funny that we both fell off our chairs laughing. I’ve since appropriated it and, while adjusting it to meet my (disappearing) hairline, turned it into a doll. It’s ugly and wears a striped shirt. Sometimes it’s a balloon. It has even changed species.

Jules: What is your favorite word?

David: “Monkey.” I don’t know why. I just like to say it.

Jules: What is your least favorite word?

David: Hmm, I’m not sure. A lot of the worst words really do work for what they mean, like “unctuous” or “pus.” “Ointment” is particularly gnarly.

Jules: What turns you on creatively, spiritually or emotionally?

David: Great art, the natural world, kindness, honesty, my wife.

Jules: What turns you off?

David: Bad art, hypocrisy, cruelty.

Jules: What is your favorite curse word? (optional)

David: I’m not English, and I never say it, but I love “wanker.”

Jules: What sound or noise do you love?

David: The pop of a cork.

Jules: What sound or noise do you hate?

David: Private cell phone conversations in public.

Jules: What profession other than your own would you like to attempt?

David: Professional ball player, either baseball (which I was okay at) or soccer (of which I’ve never had any of the requisite skills or talents, but it seems so glamorous).

Jules: What profession would you not like to do?

David: Banker. It seems like a fine job, but I don’t really like dealing with money, I’m terrible at math, and I don’t really like to shave.

Jules: If Heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?

David: “Well, you certainly kept me waiting.”

All art is used by permission of David Soman.

The spiffy and slightly sinister gentleman introducing the Pivot Questionnaire is Alfred, copyright © 2009 Matt Phelan.

What a pleasure to read… I should be doing my own artwork, finishing a cover design, laying out a dummy… but why is it so much more fun to read about how YOU do it?! Thank you for sharing it.