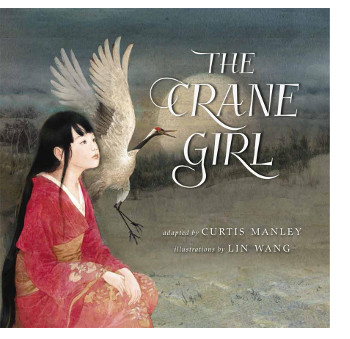

The Art of Lin Wang

March 7th, 2017 by jules

March 7th, 2017 by jules

(Click to see text and spread in its entirety)

We don’t see picture book adaptations of folktales as often as we used to. As Betsy Bird wrote here at the tail end of 2016:

A generation ago, fairy tales and folktales were ubiquitous. Because libraries made up a significant share of the book buying market, they could set the terms. And what they liked were fairy and folktales. The publishing industry complied and life was good. The rise of big box stores, to say nothing of the internet, heralded the end of the fairy/folktale era. With libraries only a fraction of the buying force, the picture book became king and the fairy and folktales almost disappeared entirely. It’s only in the last few years that small publishers have picked up the slack. While The Big Six become The Big Five, soon to be The Big Four, small independent publishers are daring to do what the big guys won’t. Publishing these books has become a kind of rebellion with kids reaping the benefits.

That’s a good summary of what happened. Today, I’ve got a few spreads from Curtis Manley’s The Crane Girl, illustrated by Lin Wang (Lee & Low, March 2017). Not only is this a picture book folktale, still an unusual thing to see, it’s actually an adaptation of more than one Japanese folktale. In a closing note, the author writes:

In the West, only two versions [of this story] are known well. In The Crane Wife (Tsuru Nyobo), a young man rescues a crane and then gives shelter to a mysterious young woman. They fall in love and get married, but when she begins weaving wonderful cloth, his greed and curiosity drive her away. In the version known as The Grateful Crane (Tsuru no Ongaeshi, literally “the crane’s return of a favor”), an old, childless couple gives shelter to a young woman, but again the crane leaves when her identity is discovered.

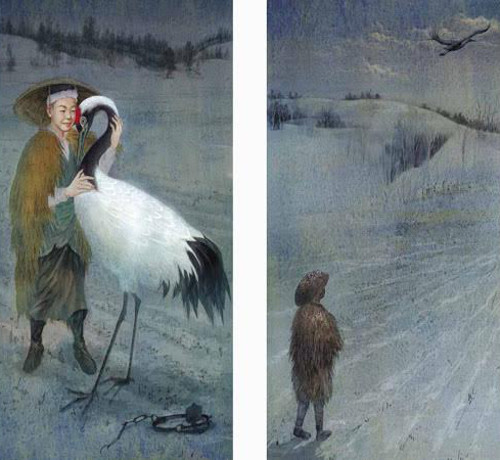

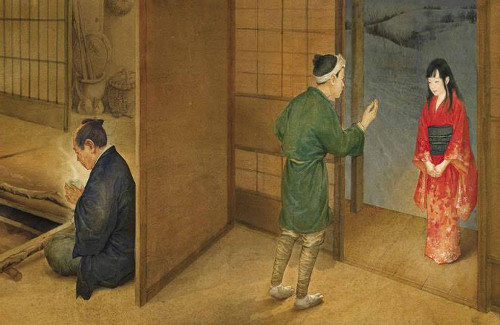

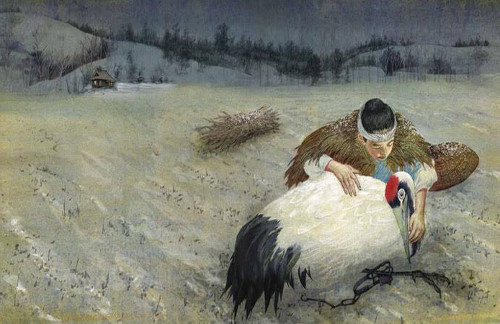

He goes on to say that, in other versions, various animals take the place of the crane. In The Crane Girl, he resets the story with a young boy, Yasuhiro, who saves an injured crane. The crane later appears in human form at the boy’s home. The boy and his father agree that this mysterious girl can stay if she works hard and contributes to the income. She offers to weave silk for them to sell at the market. Greed for the beautiful silk she produces in private (the one rule is for them to never open the door while she works) changes Yasuhiro’s father in disastrous ways, and it’s eventually revealed that she is the same crane the boy once saved. (But I can’t give away the entire story, can I?)

He goes on to say that, in other versions, various animals take the place of the crane. In The Crane Girl, he resets the story with a young boy, Yasuhiro, who saves an injured crane. The crane later appears in human form at the boy’s home. The boy and his father agree that this mysterious girl can stay if she works hard and contributes to the income. She offers to weave silk for them to sell at the market. Greed for the beautiful silk she produces in private (the one rule is for them to never open the door while she works) changes Yasuhiro’s father in disastrous ways, and it’s eventually revealed that she is the same crane the boy once saved. (But I can’t give away the entire story, can I?)

The story alternates between prose and haiku, and it’s quite effective. The closing author’s note also includes more information on Japanese poetic forms. (I did not know till now that it’s “not strictly true” that a haiku must have a pattern of 5-7-5 syllables.)

Wang’s watercolor paintings are rich and detailed. It all adds up to an enchanting story, one that bows to tradition while simultaneously striking new ground. Here are a couple more spreads:

He stroked the soft feathers on its long neck with his fingertips, and the bird

gently pressed the red top of its head against Yasuhiro’s face. …”

(Click to see text and spread in its entirety)

found a girl standing there, pale and shivering, tears frozen on her cheeks. …”

(Click to see text and spread in its entirety)

THE CRANE GIRL. Text copyright © 2017 by Curis Manley. Illustrations copyright © 2017 by Lin Wang. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Lee & Low Books, New York.

Wow. Those are some stunning illustrations. The color and texture and mood are really arresting.

Every kid who reads this is going to want to be IN this book. I now want a crane. These are so beautiful, and that shock of red in every frame just … pops.