What I’m Doing at Kirkus This Week,

Plus What I Did Last Week, Featuring Barbara McClintock

July 20th, 2018 by jules

July 20th, 2018 by jules

Over at Kirkus today, I’ve a Swedish picture book import.

That is here.

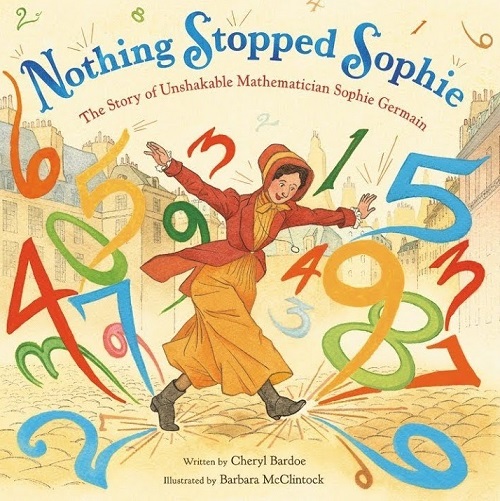

Last week, I wrote here about Cheryl Bardoe’s Nothing Stopped Sophie: The Story of Unshakable Mathematician Sophie Germain (Little, Brown, June 2018), illustrated by Barbara McClintock. Today, I’m following up with some images from Barbara, which include what she calls “inspiration, sketches, little tiny cut-out things, and lots of double-stick tape.” She takes us through the process of creating several of these beautiful spreads, and some final art is included. I thank her!

Enjoy. …

Barbara: Finding a way to illustrate Cheryl’s manuscript was a challenge. If I’d used a strictly visual interpretation of the text, the illustrations would have been 32 pages of Sophie sitting at a desk, slowly getting older. Not very exciting, visually. I frequently had to rely on visual metaphor to show Sophie’s growth as a mathematician, as well as her accomplishments.

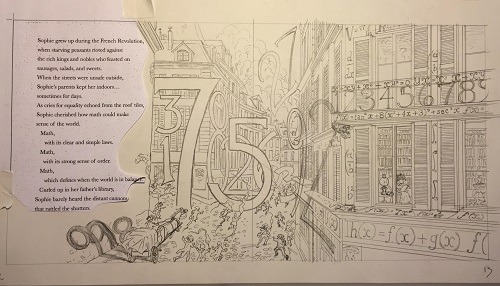

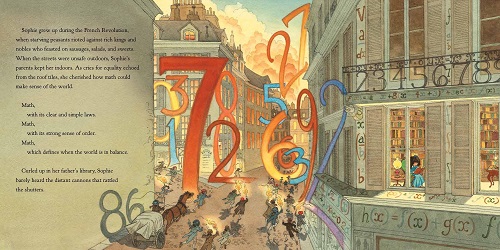

The text talks about Sophie staying inside her family library, as chaos raged in the streets below her window. I knew I wanted to feature numbers in some way in the drawing. As I looked for inspiration for this picture, I found images of giant sculptures of numbers by the American pop artist Robert Indiana.

And that gave me an idea. I decided to use numbers as characters in the picture, showing the fury and anger of the fighting outside. But the numbers, as they become ordered and structured, become part of a stable, protective environment surrounding Sophie’s window.

Sophie barely heard the distant cannons that rattled the shutters.”

(Click each to enlarge and to read the full text)

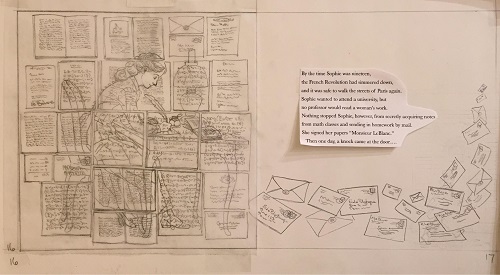

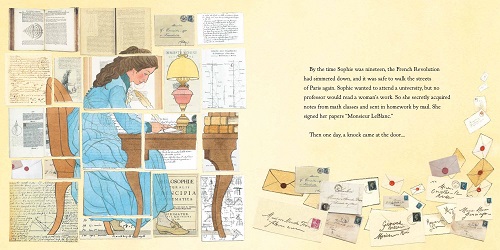

Some illustrations were more challenging than others. This bit of text, about Sophie secretly taking math classes by mail and using a man’s name rather than hers, could have been illustrated by just showing Sophie writing at her desk. Or maybe writing at her desk for hours, days, weeks, months … not the most exciting image. I also wanted the reader to see what she was reading and writing. And how could I show all those letters being sent back and forth to her professor?

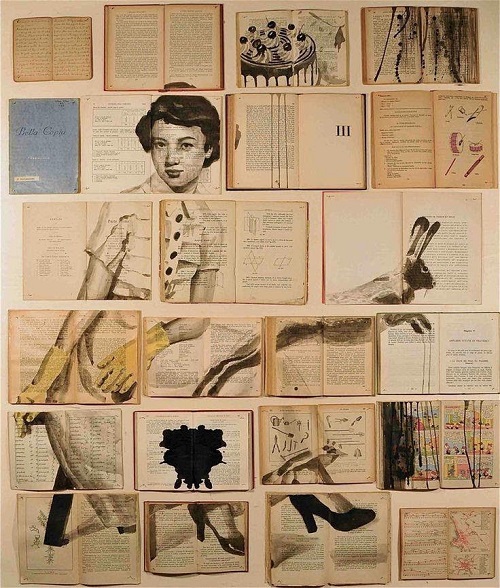

One day, I saw this piece of art online …

… and everything clicked. I could show Sophie hard at work — but also show the books, letters, and her writing all at once! I’d never done collage before, but I knew this was the perfect way to visually narrate the text. So, I plunged in.

Here’s my sketch of the collage idea:

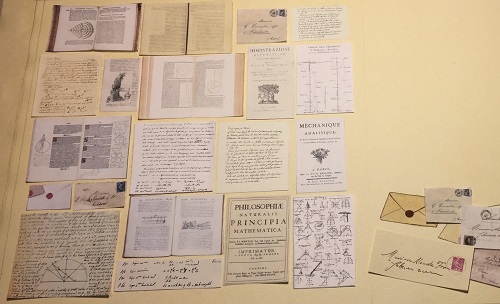

I found images of old math books from the time period when Sophie was studying. I also found examples of her hand-written notes, as well as old letters and stamps. Once I’d copied, cut out, and taped all of the images onto a watercolored background …

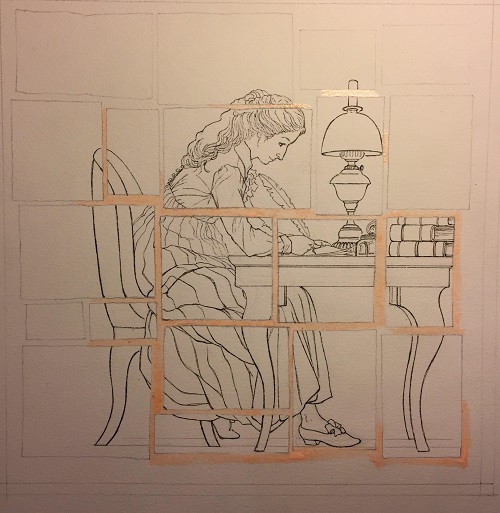

… I drew the image of Sophie at work, leaving white space where the spaces occurred around the book images on the collage sheet.

And then I used watercolors to color the image of Sophie.

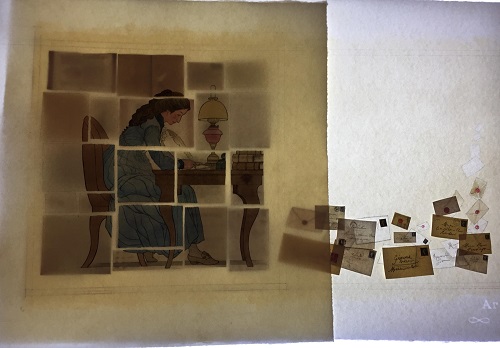

On a light box, I overlaid the painting of Sophie onto the collage …

… and adjusted the images.

I am a total luddite when it comes to computers. I can send emails, and I recently figured out how to make DropBox folders. But I don’t use any digital work in the creation of my pictures. I relied on the expert care and eye of Saho Fugii, my art director, to do her digital magic and make the two separate images work together. Thank you, Saho. It takes a village!

(Click each to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

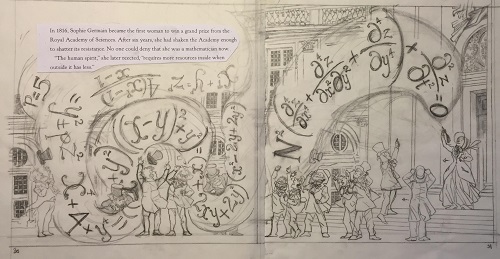

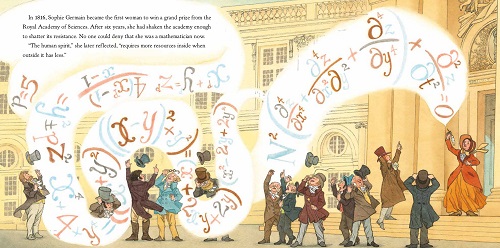

Sophie ultimately won the math competition. Initially, we thought she strode up to a stage to accept her award and to be presented with a medal in front of an audience comprised entirely of male mathematicians. Then we thought perhaps she might have been too modest to walk onto stage in front of a crowd and that it might be more accurate to depict her sitting in the audience, listening to the announcement of her award.

A key difference between the author part and the illustrator part of bookmaking is that an author can write something like “Sophie accepted her medal,” but the illustrator has to find an accurate image of the medal to depict in the illustration. In my efforts to find an image of that medal, I discovered that Sophie didn’t actually attend the award ceremony. So, back to the drawing board, using a conceptual approach to the artwork.

At first I thought of showing a long pathway of numbers — starting with basic math going all the way up to Sophie’s winning equation, with Sophie at the top of the pathway — but her accomplishment included her victory over an all-male system. So, we wanted to include a few puzzled-looking men viewing this pathway of equations. However, there was no physical context to ground this image in time or place.

Art director Saho Fugii and my editor Deirdre Jones suggested including the Science Academy building in the picture — to provide that sense of place. Originally, the building was dominant in the picture. Saho felt our focus should be on Sophie, the math, and the men. I scaled back the size of the building and zoomed in on the characters. And this time, everything fell into place with the drawing.

win a grand prize from the Royal Academy of Sciences. …”

(Click each to enlarge and to read the full text)

I love this illustration. It shows Sophie standing proudly on the steps of the Academy, her award-winning equation flowing out of her pen, blowing the hats and coattails off all the men who could no longer deny this bold and brilliant woman’s entry into the history of profound mathematical discoveries. And I never did find an image of her award medal, if one ever existed.

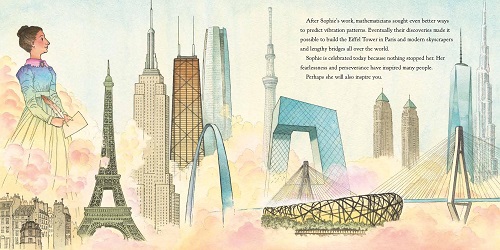

to predict vibration patterns. …”

(Click image to enlarge and to read the full text)

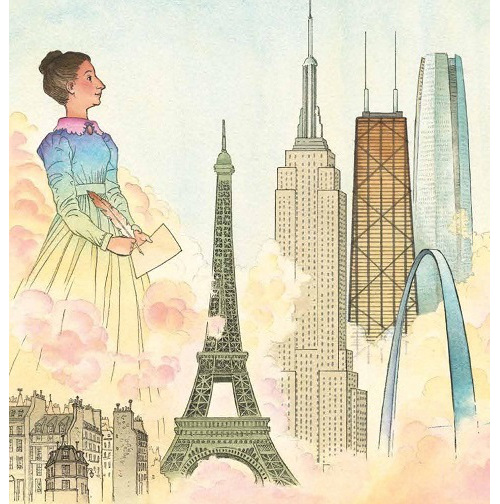

Sophie’s sound vibration equation is the foundation for all vibration theory that followed. Her initial discovery and work has allowed tall buildings, long bridges, and other modern engineering accomplishments to occur. I’ve included buildings from around the world in this illustration [above] to show the breadth and impact of Sophie’s genius.

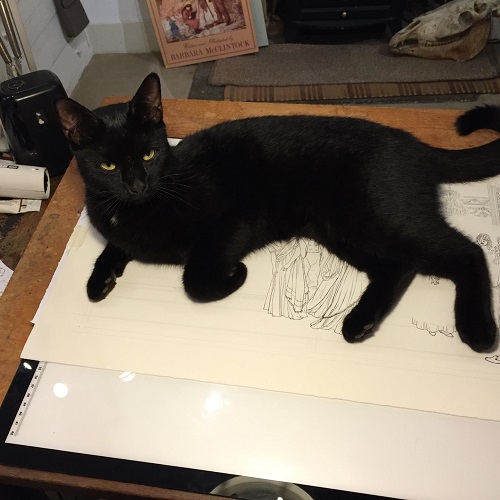

While I’m working, I have plenty of help from my cat, Louis. This image proves that you can’t get too precious about your original artwork — and that it’s important to make sure there’s no cat hair on the finished art before you send it to your editor.

NOTHING STOPPED SOPHIE: THE STORY OF UNSHAKABLE MATHEMATICIAN SOPHIE GERMAIN. Text copyright © 2018 by Cheryl Bardoe. Illustrations © 2018 by Barbara McClintock. Published by Little, Brown and Company, New York. All images here reproduced by permission of Barbara McClintock.

My goodness – another book I’ll have to get just for the juxtaposition of words and images. I love the disordered jumble of numbers (honestly, how I see them) and the orderly marching along, which soothes the mathematician. Sophie is TRULY lovely!!!!

[…] a July visit to my site, McClintock wrote about her decision to rely on visual metaphor: “If I’d used a […]