Thanks to Frances Perkins:

An interview with Kristy Caldwell

August 13th, 2020 by jules

August 13th, 2020 by jules

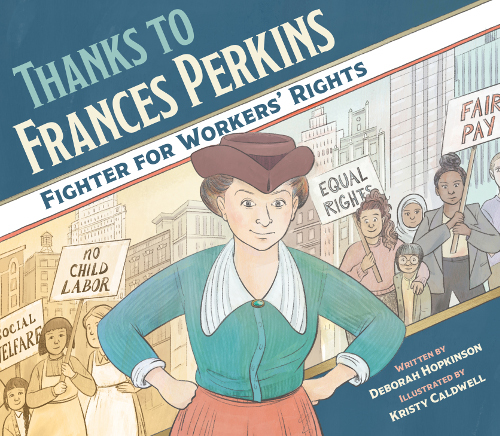

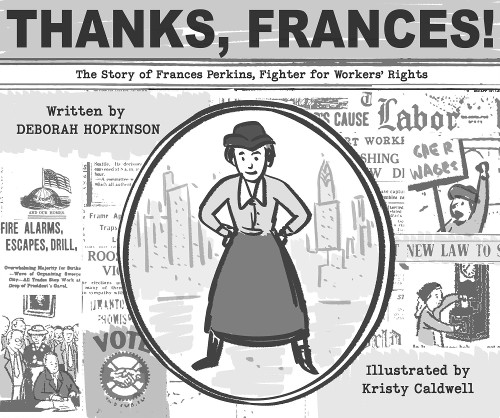

I’m pleased today to welcome illustrator Kristy Caldwell to 7-Imp as part of a blog tour for Deborah Hopkinson’s Thanks to Frances Perkins: Fighter for Workers’ Rights (Peachtree, August 2020). Hopkinson frames this biography of the groundbreaking workers-rights advocate, who served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor (the first woman appointed to a presidential cabinet) for twelve years, with “math questions” for the young readers at whom the book is aimed: “How many yeras will it be until you turn sixty two?” and “What year will that be?” You’ll want to thank Frances Perkins, Hopkinson writes, when you get to that age.

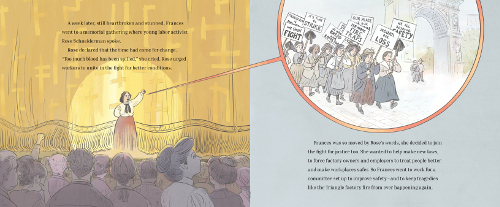

From there, readers meet Frances as a young girl and follow her life and career until the moment the Social Security Act was signed into law on August 14, 1935. Reverently and passionately, Hopkinson stresses Perkins’s desire to fight for social justice, make workplaces safer, and “help neighbors in need”—she was significantly impacted by witnessing the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and, afterwards, inspired by the words of activist Rose Schneiderman—as a woman who trusted in “both her heart and her mind.”

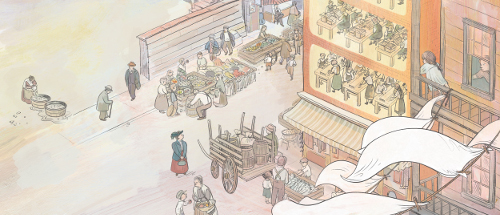

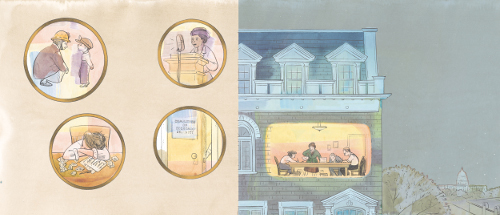

Kristy’s soft, fine-lined illustrations brim with details, and she’s here today to talk about the book, share some process images, and show some final art. I thank her for sharing! Here she is — in her own words.

Kristy (pictured above): I’ve been aware of Deborah Hopkinson since I interned a long time ago at Schwartz & Wade Books. So, when I saw her name on this manuscript, I was definitely excited. I have a copy of A Boy Called Dickens, written by Deborah and beautifully illustrated by John Hendrix, on the bookshelf next to me right now. She has a light touch with text that feels special. It leaves a lot of room for the illustrator to make choices, and when I first read the manuscript for Thanks to Frances Perkins, I felt intimidated by that freedom. In a good way.

This was the first I’d read about Frances’s life. And that’s something I love about my job. As soon as I started working on the book, it felt like Frances Perkins was everywhere. Elizabeth Warren was mentioning her on the campaign trail. One of Frances Perkins’s big goals in 1933 was tackling universal healthcare, and here we are debating it all over again. I see protests happening in the same locations as the protests Frances saw. She was always here, but now my eyes are open to her in a new way.

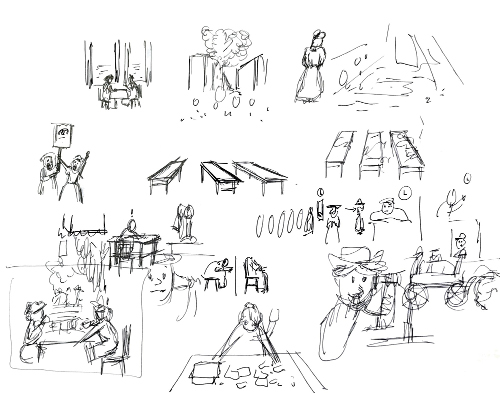

(Click each to enlarge)

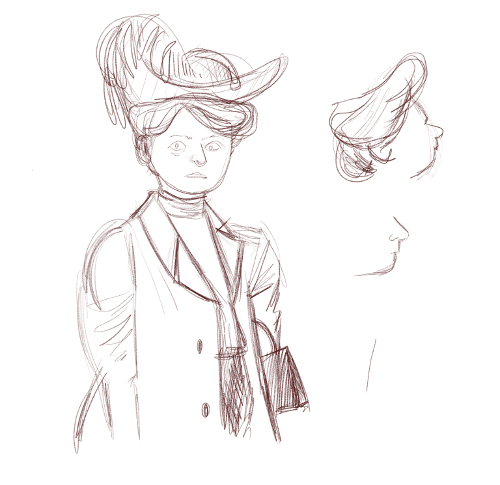

I have a habit of going down the rabbit hole with little fiddly details, and I tried to rein in that tendency this time. That might sound strange, because of course you want the details to be right, but I can suffocate myself with it sometimes.

That being said, I did research! I read a very good biography of Frances, Kirstin Downey’s The Woman Behind the New Deal. That gave me a great sense of her as a person. For instance, she was very politically savvy. She didn’t just fall into social work. She pursued it, and she took notes on what worked and what didn’t. She deliberately dressed in a severe, no-nonsense way, because she felt that helped her be taken seriously. Her clothes weren’t a big deal to her, but their effect on other people was. That kind of insight into her character was a lot more helpful than just researching the fashion of the era. Which, of course, I also did. There are also plenty of archived newspapers from her era, which gave me a different perspective on the unrest across the country at that time.

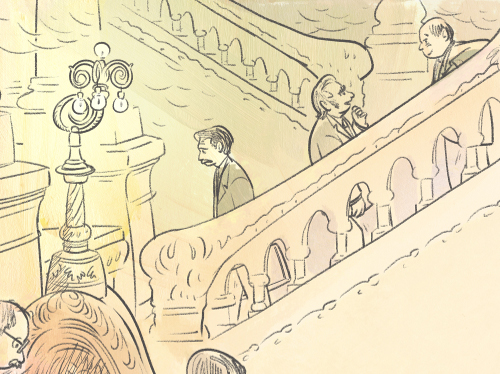

And because I’m in New York, I was able to trace her footsteps through old tenement areas, Washington Square Park, Columbia University, and the Metropolitan Opera House.

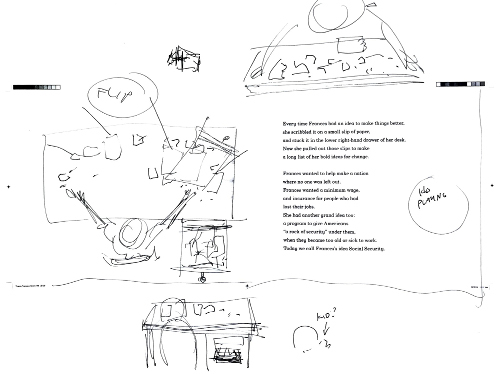

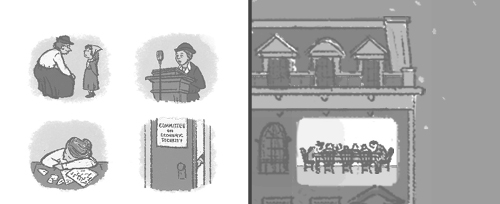

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

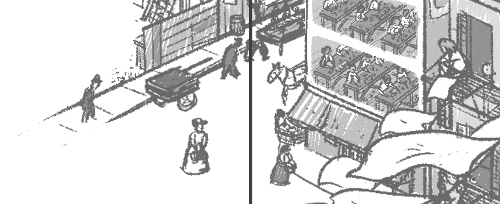

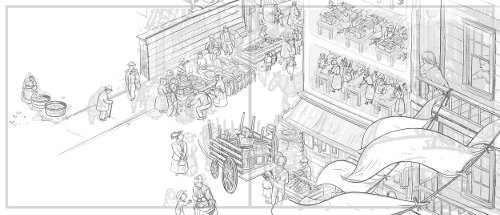

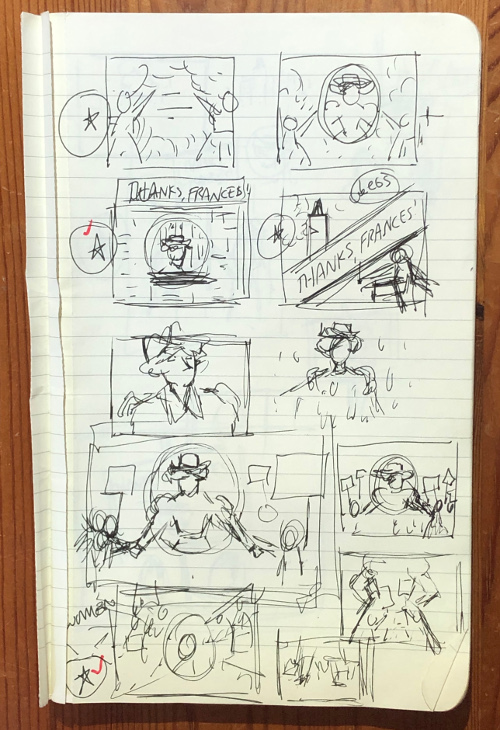

These illustrations are a weird mix of digital and analog. The first thing I always do is print out the manuscript; get away from my desk and computer (this time I parked myself at a local coffee shop); and cover the pages in notes and small drawings, a loose collection of ideas. Then I move into very small digital sketches. The process for each book varies from here, but after these sketches were approved, I used my Cintiq like a light box: I turned down the opacity of the sketches until the lines were barely visible, and I drew on a new layer.

ink final, and color final (without text)

(Click each image to enlarge)

So, for this book the sketching and inking was mostly digital. And it’s all very clean and tidy. But I wanted the coloring process to introduce something different. Frances is fascinating to me, because she embodies two extremes: someone who actively engaged with people but also spent long, isolated hours slogging it out in bureaucracy.

color process, and color final (without text)

(Click each image to enlarge)

And then, unrelatedly, I was spending a lot of time looking at the concept art from Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians—the original, animated feature—and when I shared that with my art director, Adela Pons, she completely got it. So, I brought that outside obsession into the mix as a color inspiration. I started with acrylic paint, and it snowballed into a surprisingly fun process. I printed out my drawings, taped them to a real light box, and painted onto a new sheet of paper in a really unplanned, messy way. For a couple of pages, I created solvent image transfers of the printed drawings and painted on top of those. I tightened it up as I went, and I scanned in whatever I liked and combined it all together. There are also some other paints and pencils, here and there.

(Click each image to enlarge)

The page that shows the newsboy and the line of men during the Great Depression [see below] is probably my favorite single page. It’s the first page I colored, and once I saw it finished I thought, “Okay, this can work.” It came out pretty close to what I had in my head.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click the illustration, which is sans text, to enlarge)

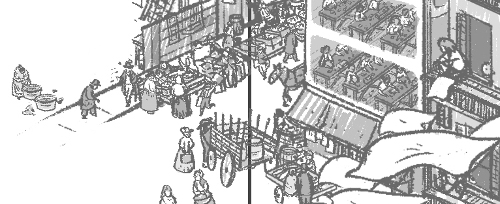

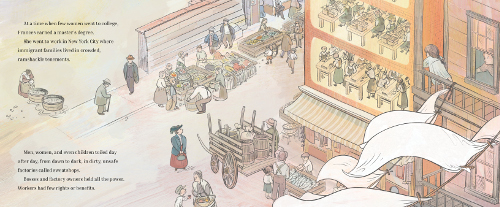

But as far as full spreads go, I like the shot of the NYC tenements, early in the story. That took a long time, and it felt like a personal victory when it was finished. My favorite detail is the little girl at the top right, leaning on her balcony.

crowded, ramshackle tenements. …”

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

Frances was a great salesman for her ideas — and funny. She could dish it out as well as anyone who tried to trip her up. When she was asked if gender held her back, she said, “Only in climbing trees.” That was right around the time of her nomination for Secretary of Labor.

she decided to join the fight for justice too. …”

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

I think Deborah did a great job of pointing out that Frances had support. She was inspired by speakers and protestors who had been there before her; she served on committees with people who were interested in the same things; and she made changes that are still in place today, thanks to the stewards who came after her. She also had family issues that made it hard to move to D.C, and, to make it work, she moved in with a friend. I think we all need to hear that even infinitely capable people aren’t doing it alone.

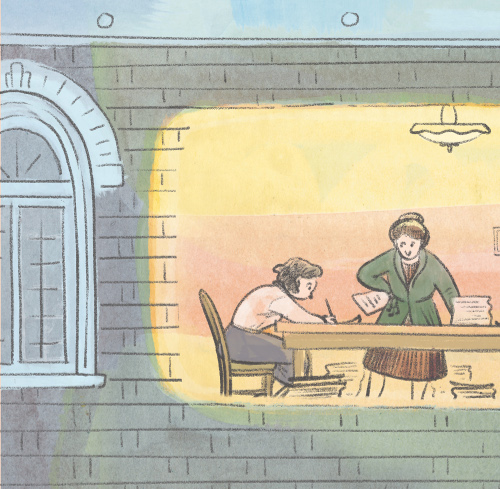

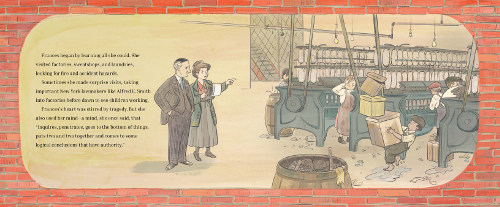

She visited factories, sweatshops, and laundries,

looking for fire and accident hazards. …”

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

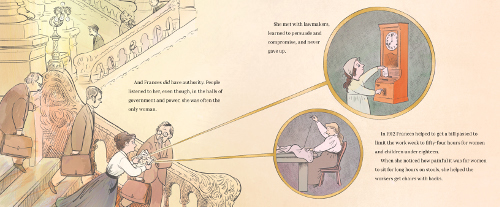

in the halls of government and power, she was often the only woman. …”

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

Many thanks to Kristy! Bonus: Below is a series of photos that shows the making of the book’s cover, including cover thumbnails, sketches, and the final cover art.

THANKS TO FRANCES PERKINS: FIGHTER FOR WORKERS’ RIGHTS. Text copyright © 2020 by Deborah Hopkinson. Illustrations © 2020 by Kristy Caldwell. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Peachtree, Atlanta. All other images reproduced by permission of Kristy Caldwell.

To read more about the book, here is the schedule for the Thanks to Frances Perkins blog tour:

- Monday, August 10: The Tiny Activist

- Tuesday, August 11: Raise Them Righteous

- Wednesday, August 12: Kidlit Frenzy

- Friday, August 14: Nerdy Book Club

A great interview on a beautiful book. I hope my book on this inspiring American hero does as well as I’m sure this one will.