If You Come to Earth:

A Conversation with Sophie Blackall

October 5th, 2020 by jules

October 5th, 2020 by jules

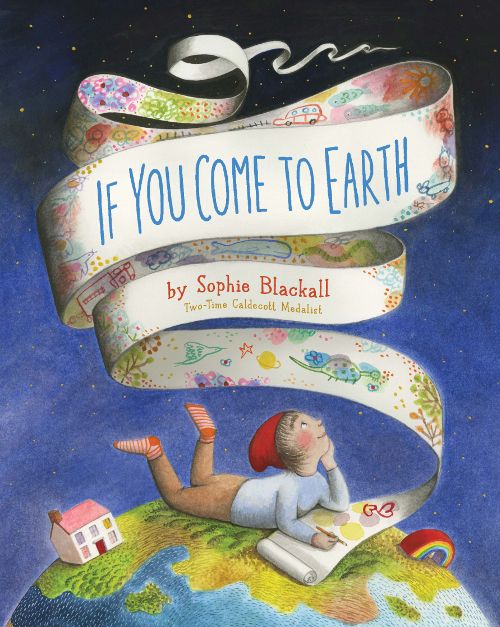

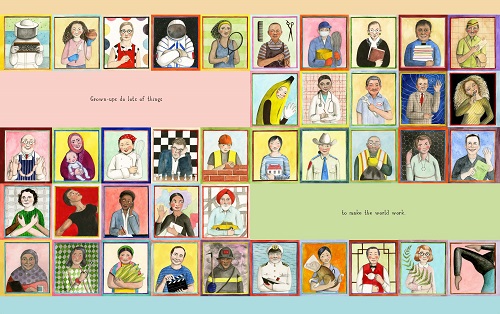

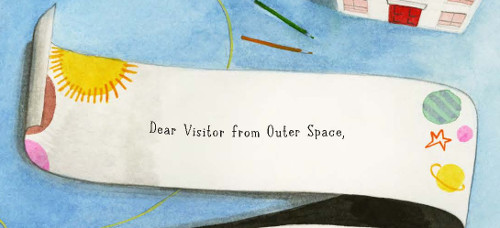

Author-illustrator Sophie Blackall and I have been chatting back and forth via email about her new picture book, If You Come to Earth (Chronicle), which arrived on shelves last month. It’s an ambitious picture book that asks big questions about life, and it’s funny and poignant and thought-provoking all at once. Our narrator, Quinn, writes a letter via scroll to any aliens who are perhaps considering visiting Earth. What is Earth like anyway? That’s the question Quinn poses. Not a small task, but over the course of 80 pages, they manage to cover a lot of ground.

I asked Sophie about the book’s genesis, and she also talks to me about the challenges of creating a book with such a wide scope—and why the tiny details in such a story matter and matter a lot. A transcription of our chat is below. There’s also lots of the book’s dynamic, exquisite art in our chat, and I thank her for sharing. Let’s get to it!

Jules: Hi, Sophie. So, you were just telling me this book has been seven years in the making? Do tell me more.

Sophie: Hi, Jules. Yes! It was a very long gestation.

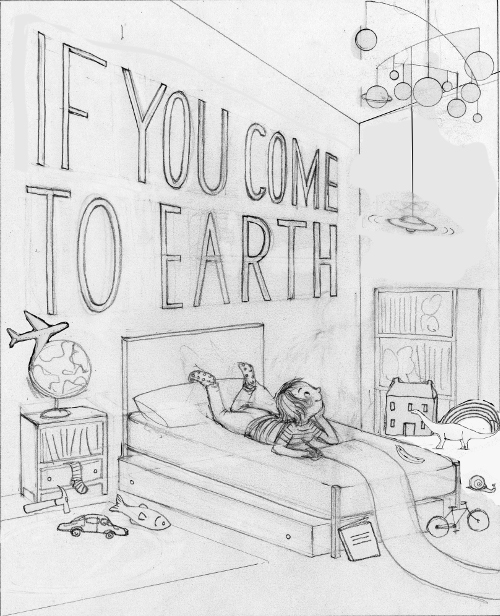

Out of curiosity, I just went back to look at the first draft for If You Come to Earth. Most of my manuscripts go through significant metamorphoses and are almost unrecognizable from initial to final drafts, but the funny thing is: This first draft is almost identical to the finished book. A couple of paragraphs switched order and the title was originally Dear Alien, but that book already exists. Other than that, the manuscript came out almost fully formed.

But heavens to Betsy, those drawings took years. Victoria Rock is one patient editor.

It was a rather ambitious idea—to try to explain the world in a picture book. And I quickly realized, even with eighty pages (EIGHTY!), it would be impossible to include everything. So, I decided that this is one kid’s description of life on Earth. They will leave things out. And maybe the omissions will inspire other kids to think about what they would include in a letter to a visitor from another planet, explaining the world.

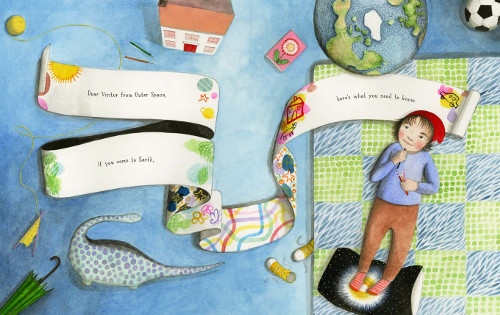

If you come to Earth, here’s what you need to know.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: I suspect authors hate being asked about inspiration, but what was the genesis for the story? And don’t you say in the closing note that nearly everyone in the book is based on a real person you’ve seen in your travels over the years?

Sophie: No, I love that question, because for once I have a good answer!

The idea for If You Come to Earth came to me on top of a Himalayan mountain in Bhutan. I was working with Save the Children, and we had climbed a zig-zagging path to reach a tiny, two-room school with ten students. We couldn’t understand a word each other said, but the children drew pictures for me and shared their lunch. And I showed them some books. These kids had maybe only seen one or two books in their lives, limp-paged, worn text books with dated drawings. Over the years I have made books about friends and babies and bears and lighthouses, but what I needed in that moment was a book that would connect us. A book about their home and mine. Traveling with Save the Children and again with UNICEF, I met more children in Rwanda and Congo and India and promised I would try to make a book about all of us and the planet we share.

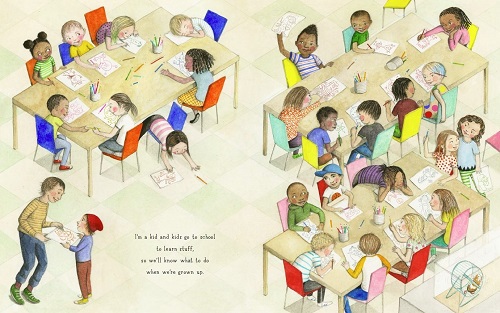

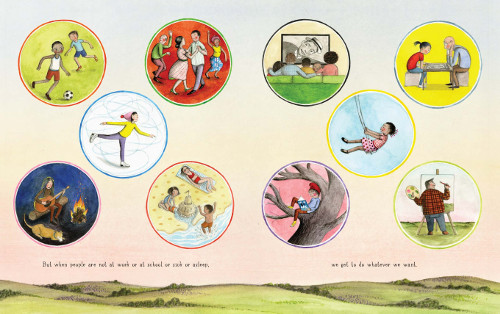

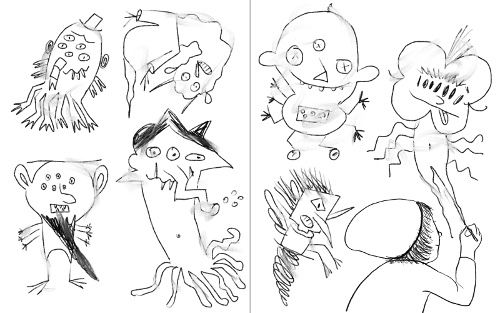

Back in New York, I invited myself into a second-grade classroom at the Brooklyn New School, and over six weeks my 23 new best friends and I talked about the existence of life outside this galaxy, what makes us human, what we love the best about our planet, and the things we most need to fix. Those kids are all there in If You Come to Earth, even though they are now far-flung in middle school. The drawings they are making on those pages are actually some of the pictures that kids across the country helped me make in school visits over the past few years, when together we imagined what life on other planets might look like.

so we’ll know what to do when we’re grown up.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

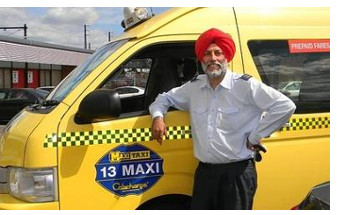

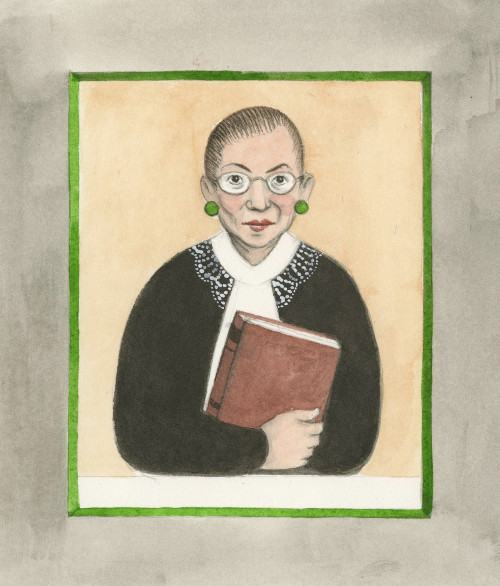

As for the people in this book being real, that’s true! Or almost true. Just about everyone in If You Come to Earth is someone I know or met or saw—in airports and on subway trains, in markets and picnicking in parks. Or they are public figures (like Ruth Bader Ginsburg or Carla Hayden or Beyoncé) or real people I found on the internet in various professions, like Lakhwinder Singh Dillon [pictured here], the honest taxi driver in Australia who returned $110,000 Australian dollars to a man who’d left it behind. One person who is not real, but will be recognized by many, is little Peter from Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day, one of my favorite books.

As for the people in this book being real, that’s true! Or almost true. Just about everyone in If You Come to Earth is someone I know or met or saw—in airports and on subway trains, in markets and picnicking in parks. Or they are public figures (like Ruth Bader Ginsburg or Carla Hayden or Beyoncé) or real people I found on the internet in various professions, like Lakhwinder Singh Dillon [pictured here], the honest taxi driver in Australia who returned $110,000 Australian dollars to a man who’d left it behind. One person who is not real, but will be recognized by many, is little Peter from Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day, one of my favorite books.

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: Oh, I see him! (Just grabbed the book again). I missed that the first time.

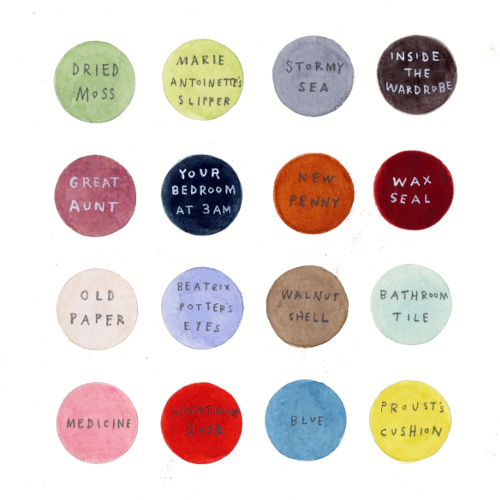

It’s so easy to get lost in the details in this book (a good thing). I love the names on the paints page. (I’m going to pretend there is really a color called “Waffle Day.”) There’s so much detail, yet the book doesn’t get lost in them. Was it hard for you to pull yourself out of the details as you wrote and painted in order to focus on the book’s through line? Does this question even make sense?

(Click spread to enlarge)

Sophie: This question does make sense, and I love you for asking it.

I think you have put your finger on the very thing that was not only my main goal, making the book, but also describes the way a curious human being exists on Earth. It is through details that we come to understand the big picture, but we need to constantly zoom in and out to make sense of both. We can’t properly understand a beach without studying a handful of sand. But if we only looked at the sand, we wouldn’t see the beach. When we learn the details of our friends’ experiences, we can more fully appreciate the urgent need for social justice and equality. When we know the diversity of life on Earth, from a platypus to our second-grade teacher to a fiddlehead fern, we are more likely to care for the environment and for our fellow human beings. When we know that our planet is one grain of sand and that there are as many planets in the universe, as there are grains of sand on all the beaches in the world, then we can begin to grasp our place in that universe—and consider the unlikelihood that we are the only sentient beings among all those gazillions of planets.

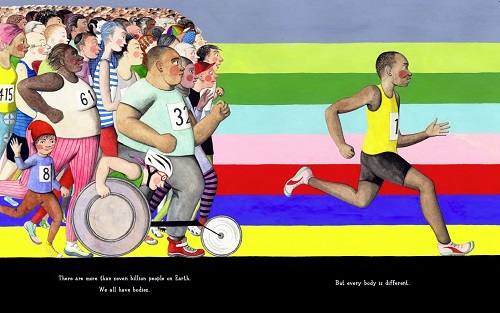

But every body is different.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

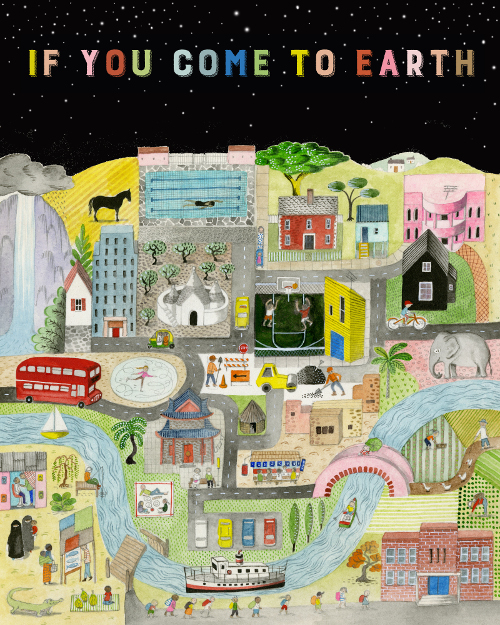

There was always the worry, making a book about the whole world, that by choosing to include some details, I must, by necessity, exclude others. But whenever I read a story, it is the details that draw me in, that give it substance, that make me believe in it—and the more specific, the better.

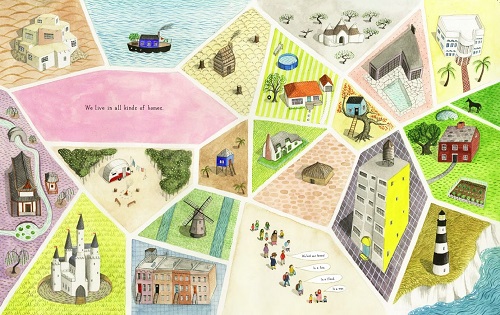

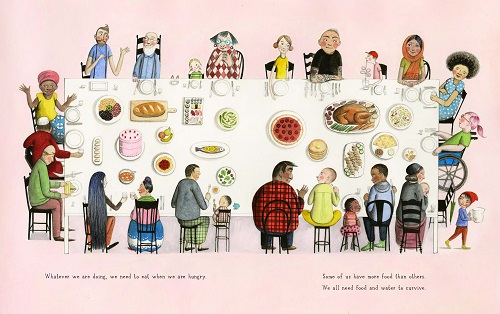

So, I tried to make every detail in If You Come to Earth count. To make those details particular and idiosyncratic and surprising and familiar. To draw a crowded bus that every Congolese person will recognize. To draw my family’s old station wagon with a Christmas tree tied on top. To show a North American roast turkey dinner and also ema datshi [pictured below], the Bhutanese dish of stewed peppers and yak cheese.

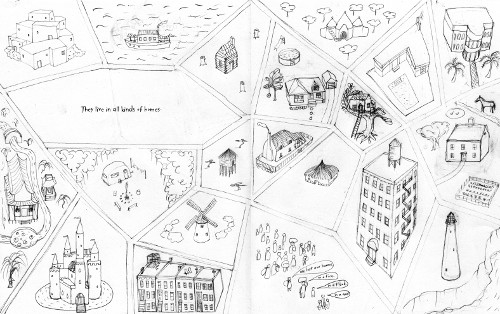

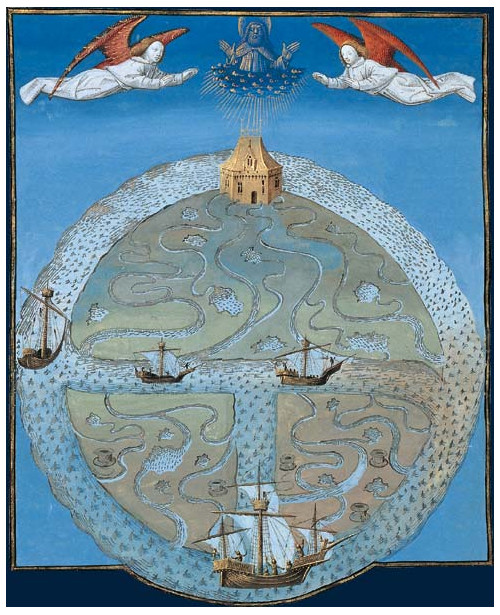

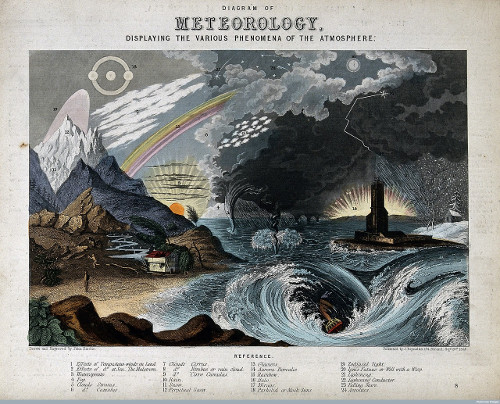

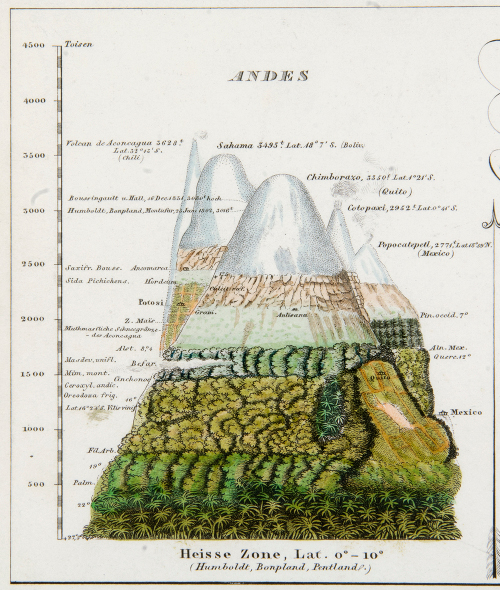

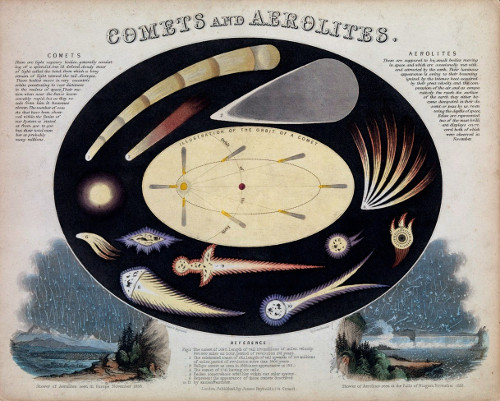

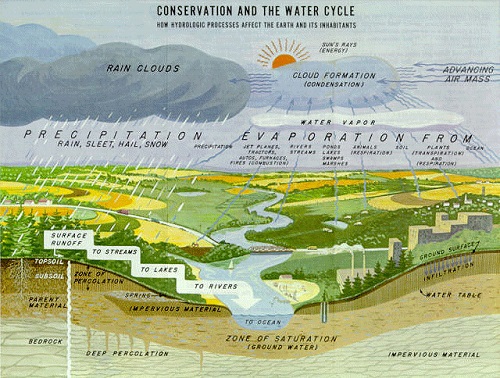

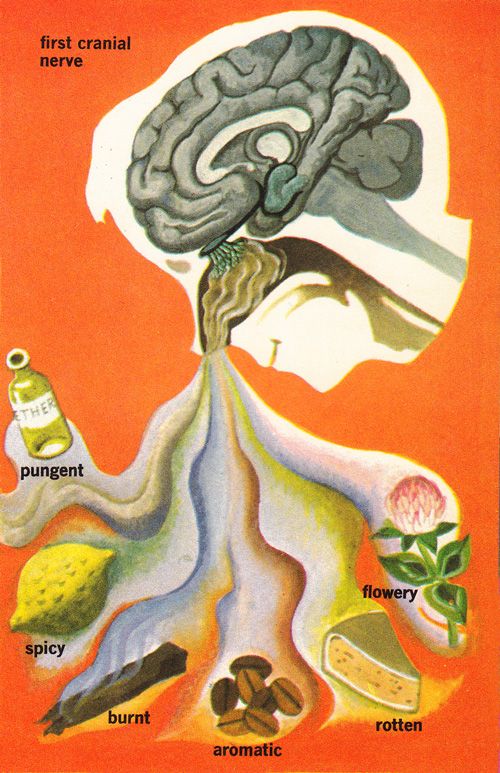

Finding a way to zoom in and out from macro to micro was challenging in the best way. I wanted kids and their grown-ups to be able to read the book in ten minutes, but also to want to spend ten minutes on each page. I have always loved information graphics, especially 19th-century diagrams and medieval maps and mid-century science charts, and I mined those materials for ideas on how to present detailed information in cohesive yet inventive ways.

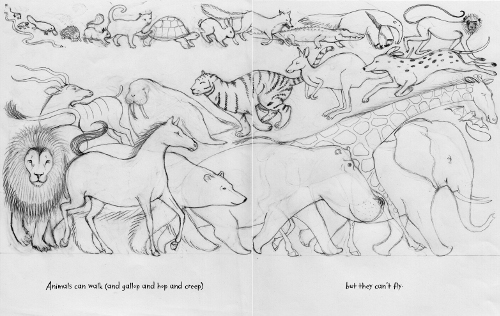

And so the spread about animals became an animated procession of beasts, arranged from smallest to biggest. And the colors you need to paint everything in the world became a page of paint tubes. And the flock of birds formed one giant bird in flight.

If You Come to Earth is framed as one child’s view of the world, but the details were contributed by hundreds of friends and strangers. The birds I chose to draw were suggested by friends far and wide, and the color names were selected from over 700 submissions on Instagram, many of which came with detailed personal anecdotes, adding another rich layer of community to the book.

And every time I got too invested in the story behind a paint color name or too focused on the markings of a peanut shell, I would step back and think of our planet rotating and revolving in space, our planet which holds everyone we know and everyone we’ve never met and all our food and all our water and all the art and books and music, and every ant and every sneeze and every comma, every atom of every living and non-living thing.

When we remember that we are all here together on Earth—and when we are inspired by, say, a passing comet and look up to the sky—then for a moment our differences can seem insignificant and our conflicts irrelevant.

we get to do whatever we want.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Some of us have more food than others. We all need food and water to survive.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: That speaks to me. If I find myself worrying incessantly about something, I sometimes imagine myself as a speck of dust in space. That zooming-out helps put things in perspective.

I’m struck by: “I wanted kids and their grown-ups to be able to read the book in ten minutes, but also to want to spend ten minutes on each page.” I think you’ve pulled that off quite successfully here (and what a succinct way to describe the book).

Nerdy process question: What is it you love about working in Chinese inks and watercolors?

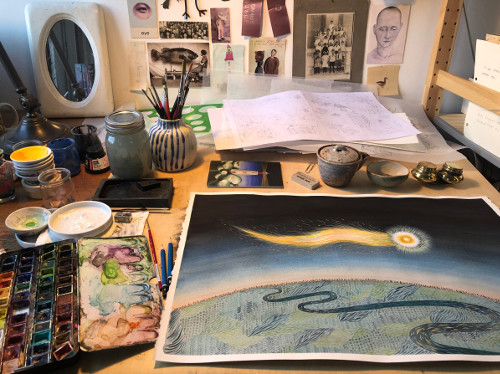

Sophie: I love nerdy process questions. I am just back in the studio after a long time quarantining in upstate New York, and I realized how much I missed the nerdy process conversations! You know I share a studio with Brian Floca, Rowboat Watkins, and Doug Salati, and we all work differently but have enormous admiration for, and interest in, each other’s process. So, to be back with the boys, talking about paper tooth and frisket and multiplying layers was heaven.

(Click to enlarge)

I have been working with Chinese ink and watercolor for a long time now. I discovered it by accident. The Chinese ink is compressed in a stick, which is dipped in water and ground on a stone. I love this part of the process, like crushing spices and mixing a paste. It’s soothing, and I think about what I’m about to paint and the layers and color choices, while I swirl the ink around the surface of the stone. I paint all the tone and shadows with the ink, and when it’s dry I go over the top, building layers of watercolor washes. This was the bit I discovered by chance—that the Chinese ink is waterproof, so when the color is laid over the top, it doesn’t smudge. Instead, it’s like tinting a black and white photograph or hand-coloring a lithograph.

When I did a book tour in China last summer (which feels like a lifetime ago), my Chinese editor presented me with a beautiful ink stone in a wooden box, carved with lotus flowers and leaves. It’s not the most practical medium for traveling—my bags are always weighed down with my ink stone—but I can’t imagine giving it up.

(Click to enlarge)

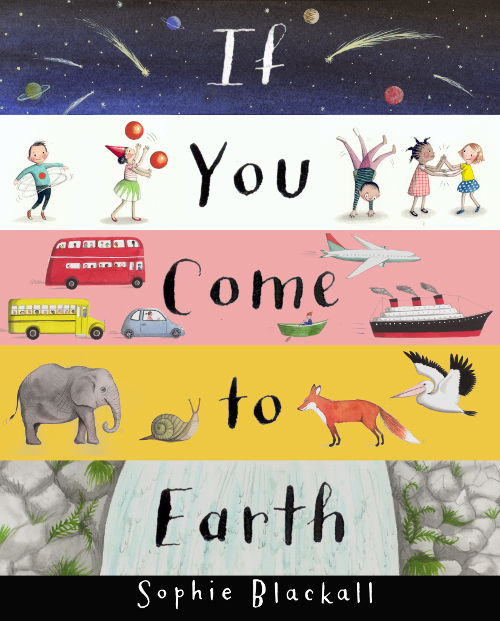

Jules: Did you have a hand in the design decisions for If You Come to Earth? I love the little design details: the hand-lettering, the cover art that differs from the jacket art, the shiny spots on the cover (which probably has a more fancy-pants name than “shiny spots”).

Sophie: If You Come to Earth was designed by Sara Gillingham, who is a genius. Sara writes and illustrates her own beautiful books, and the fact that she is willing to share her talents is indicative of the generous, wonderful person she is. We have worked together on all the Ivy and Bean books, and we also worked together with UNICEF, designing immunization campaign materials for the Measles and Rubella Initiative.

I had become very tangled up in the design challenges of the narrator’s letter in this book being a long paper scroll. I was reluctant to give up the scroll; that is one of the ancient forms of visual storytelling. A scroll is a continuous narrative, meant to be unfurled a section at a time, and is an intimate way to view images in a progression through time and space. I loved the idea of Quinn’s letter about the world being so long that they turned it into a scroll that would wind its way through the pages and out into space. I tried so many different things, but it was a mess. Sara and my editor, Victoria Rock, helped me make sense of the mess, and we eventually limited the scroll to bookend the story. It was fun to begin on the endpapers and have it billow out the window of Quinn’s house and into space and then to show it being collected by a spaceship on the back ends.

I love drawing on long paper scrolls with a bunch of kids. It becomes a true collaboration. Everyone finds their own space to draw, and the end result is bigger than the sum of its parts.

There is so much in the natural world that seems magical, like shooting stars and fireflies and phosphorescent waters, and the gold speckles on the jacket feel like that to me. I feel happy every time I look at the book and it twinkles back at me.

(Click to enlarge)

As for the aliens on the case cover, that was just pure fun. It was one of the first paintings I did, and originally it was going to be the back endpapers, with Quinn’s drawings of aliens going in the front. But then after we wrestled the scroll onto the ends, we kept the aliens as a surprise under the jacket.

(Click each to enlarge)

Jules: Thanks for chatting with me about this book, Sophie. I’ve taken up a lot of your time.

Sophie: It is always a pleasure to chat with you, Jules, and thank you for indulging me in talking at such length about the book that is so close to my heart.

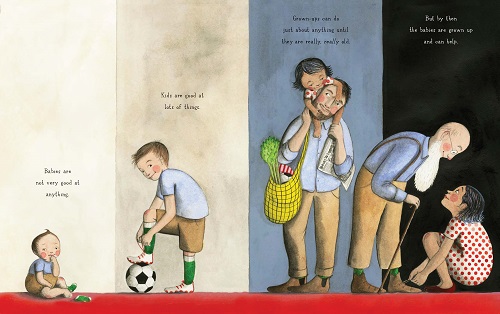

Grown-ups can do just about anything until they are really, really old.

But by then, the babies are grown up and can help.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

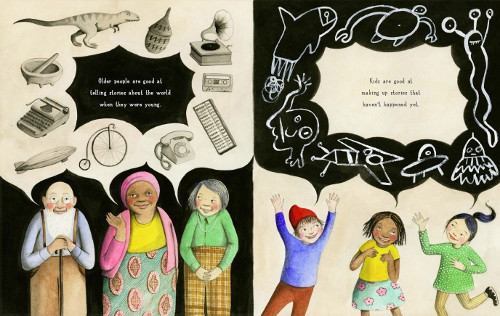

Kids are good at making up stories that haven’t happened yet.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: One last question: What’s the latest with Milkwood Farm? Is it open?

Sophie: Milkwood Farm, our conversion of a 19th-century dairy farm in upstate New York into a rural retreat for children’s book people, has kept us going during the pandemic. It has been so rewarding to see something take shape and to plan for better days ahead, when we can all gather again to eat and drink and read and write and draw and talk and listen and think. We are also keeping many workers busy, which is a good thing at the moment for our small community. Right now the bedrooms are getting their walls and floors. We are hoping to open early next summer, COVID-willing, and all will be welcome. Our website is sadly in need of updating, but you can see work in progress on Instagram @milkwoodny.

IF YOU COME TO EARTH. Copyright © 2020 by Sophie Blackall. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Chronicle Books, San Francisco. All other images reproduced by permission of Sophie Blackall.

What a lovely and joyful interview with the treasured Sophie. An intimate look at an astounding book. Thanks,Sergio, for posting the link.

Love the book … my 3yr old granddaughter and i spend ages on all sorts of things that may not be obvious to me … like the sounds the different animals make and the difference between a polar bear roar and a lions roar .. my attempt was to demonstrate was dismissed out of hand.

so THANKS … but BIG Q names of the microorganisms under the dust jacket? Or poiint me ina direction ?

Cheers Deb