Speaking the Unspeakable

January 5th, 2021 by jules

January 5th, 2021 by jules

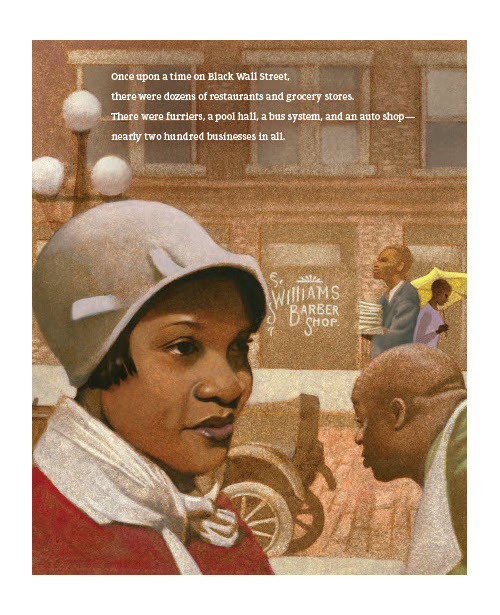

nearly two hundred businesses in all.”

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre represents one of the most heinous occurrences of racial violence in American history, yet students won’t read about it in most history textbooks. Acclaimed poet and author Carole Boston Weatherford addresses the story of the massacre and what spawned it in her newest picture book, illustrated by Floyd Cooper and on shelves early next month — Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre (Carolrhoda Books). It’s a tour de force, this one.

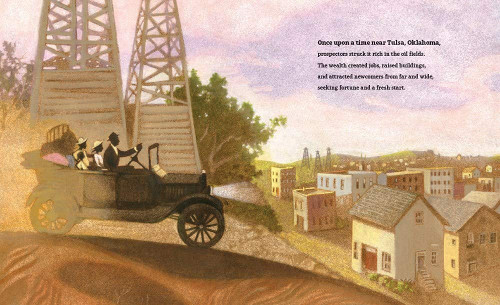

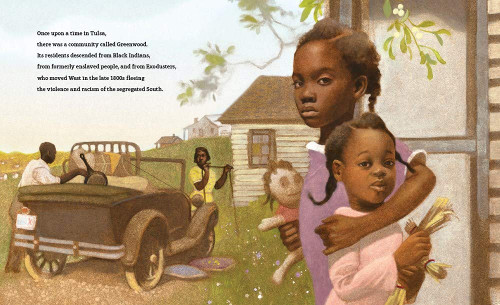

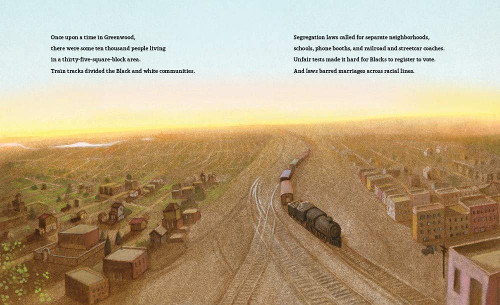

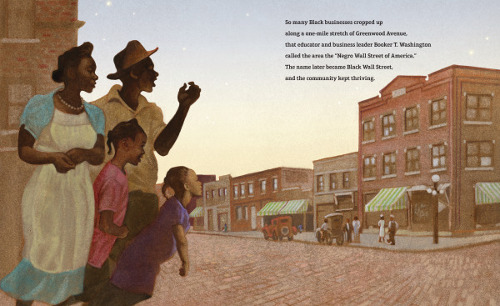

Weatherford uses, as you can see in the spreads featured here today, “once upon a time” repeatedly to establish mood in the book’s opening. It’s as if the stock phrase emphasizes the idyllic nature of the community that African Americans had created in Tulsa at this time — thriving, successful, and hopeful. “Once upon a time,” however, also has a way of indicating that change is coming. And history tells us (even if we have spoken little of it in textbooks) that change does, indeed, come to this community — in the form of white supremacy and unspeakable violence.

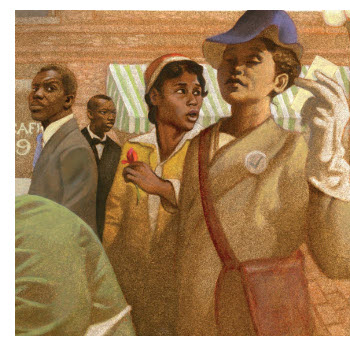

But for eight glorious spreads (approximately half of the book), Weatherford focuses primarily on the beauty of what became known as Black Wall Street (though what drove many Black people there, such as racism in the segregated South, is hardly beautiful) in the Greenwood community: the fruitful, lucrative Black-owned businesses (nearly 200 in all); the superb education Black children received; the distinguished Black luminaries who lived in the Greenwood community (including Dr. A. C. Jackson); the grand homes of the promiment leaders in town; the abandunt freedom Black people felt in the community (“Miss Mabel’s Little Rose Beauty Salon boomed on Thursdays when maids who worked for white families got coiffed on their day off and strutted in style”); and more. All that is to say: The book is about more than just the attack — and about more than the abysmal ways in which the city, and U.S. history, covered it up.

But for eight glorious spreads (approximately half of the book), Weatherford focuses primarily on the beauty of what became known as Black Wall Street (though what drove many Black people there, such as racism in the segregated South, is hardly beautiful) in the Greenwood community: the fruitful, lucrative Black-owned businesses (nearly 200 in all); the superb education Black children received; the distinguished Black luminaries who lived in the Greenwood community (including Dr. A. C. Jackson); the grand homes of the promiment leaders in town; the abandunt freedom Black people felt in the community (“Miss Mabel’s Little Rose Beauty Salon boomed on Thursdays when maids who worked for white families got coiffed on their day off and strutted in style”); and more. All that is to say: The book is about more than just the attack — and about more than the abysmal ways in which the city, and U.S. history, covered it up.

Everything changed, we read, when a 17-year-old white elevator operator accused a 19-year-old Black shoeshine man of assualt. When Black men made their way to the jail cell where the man was kept, fearing he’d be lynched, they were met by 2,000 armed white people. Violence ensued; the white mob generated rumors of a planned attack from the Black community; and then the white mob attacked Greenwood, killing up to 300 Black people, leaving more than 8,000 homeless, and burning homes and businesses to merely ashes.

In a consistently thoughtful and age-appropriate way, Weatherford writes with tenderness and reverence — “For decades, survivors did not speak of the terror” — as well as with a directness that befits a story of injustice. She notes at the book’s close when discussing Tulsa’s John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, built to remember the massacre’s victims:

It is a place to realize the responsibility we all have to reject hatred and violence and to instead choose hope.

Floyd Cooper works wonders in a book that he reveals is personal for him. (He writes in a closing note that his own grandfather grew up in Greenwood and would tell Floyd about when “the looting, shooting, and fires burned Greenwood Avenue … to the ground.”) He is a master of photo-realistic portraits, no more evident than here. Look at the cover alone — the movement, the drama, the emotion. In his closing note, he also explains to readers why this event is rightly called a massacre, not a “riot.”

Don’t miss this one. And let’s work to get it into classroom libraries. Here are some spreads so that the art and Weatherford’s eloquent words can do the talking. (And to read a Q&A about this book with Weatherford and Cooper, head to A Fuse #8 Production. As Weatherford notes in that interview: “If children of the past were—and still are—victimized by racial hatred, then today’s children can learn about it. I do not think that young readers are too tender for tough topics.”)

The wealth created jobs, raised buildings, and attracted newcomes from far and wide, seeking fortune and a fresh start.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

who moved West in the late 1800s fleeing the violence and racism

of the segregated South.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

‘Negro Wall Street of America.’ The name later became Black Wall Street,

and the community kept thriving.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

UNSPEAKABLE: THE TULSA RACE MASSACRE. Text copyright © 2021 by Carole Boston Weatherford. Illustrations copyright © 2021 by Floyd Cooper and reproduced by permission of the publisher, Carolrhoda Books, Minneapolis.