Always Leaving: A Photo Essay by Zahra Marwan

March 15th, 2022 by jules

March 15th, 2022 by jules

(Click image to enlarge)

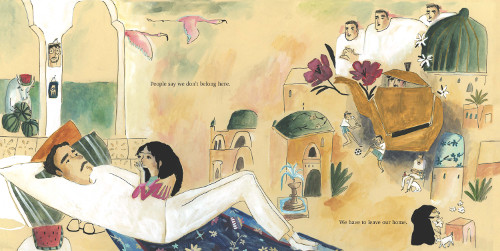

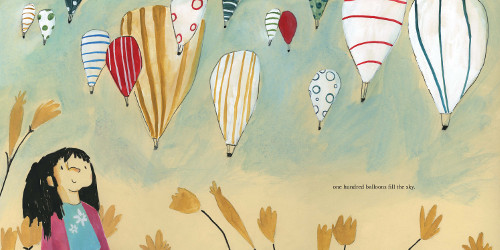

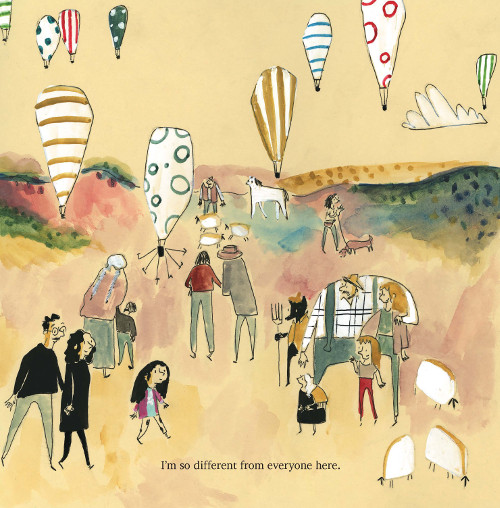

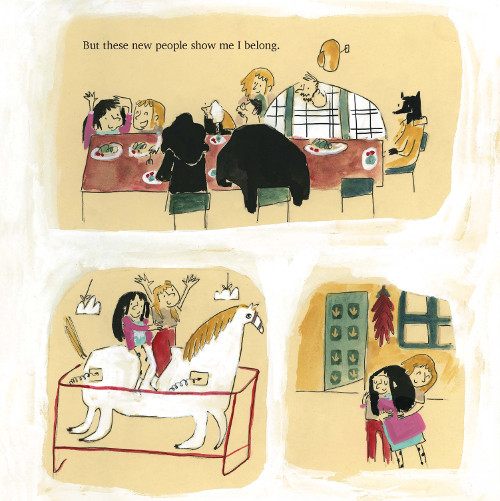

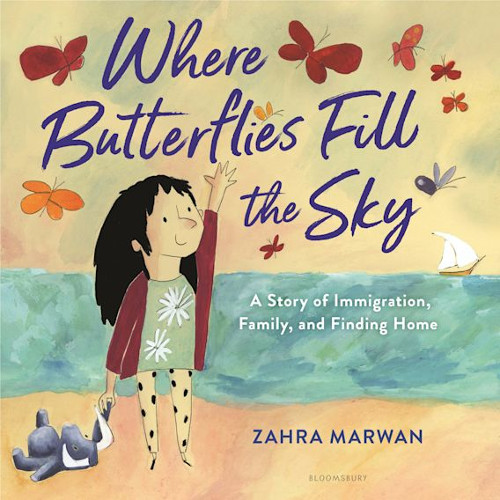

Zahra Marwan is a fine artist who, this month, sees the publication of her debut children’s book, Where Butterflies Fill the Sky: A Story of Immigration, Family, and Finding Home (Bloomsbury, March 2022). The book captures her family’s story of immigration from Kuwait, in which they were considered stateless, to New Mexico. The art in this deeply felt story is filled with motifs that represent her memories of home — and the city in the U.S. that she and her family made home. (In fact, a closing note about the art provides even more details about what readers see.)

Today at 7-Imp, Zahra contributes a photo essay about her immigration experience. Below that are some spreads from the book. I thank her for sharing.

1) I left Kuwait with my family when I was a child. I was born without nationality, and my parents wanted to make sure me and my brothers had a chance to live fulfilling lives. I was so young, but I could feel the pain of leaving. When we came to New Mexico, my identity card had written on it: “Place of birth: Kuwait. Nationality: Undefined.”

Here I am, the smaller of the two, before immigrating:

2) The first time I saw Jesus bleeding on a cross at my friend’s house in New Mexico, I was afraid I was at the home of violent people and thought I should leave. I learned to understand that we speak Arabic at home and English in public. I didn’t understand why my friend was speaking English at home.

Here is my first American friend, Bernadette:

3) Kuwait had issued us papers to leave and not return. We used those papers to return. My mom is a Kuwaiti citizen, but me and my dad weren’t. We had our papers retracted at the airport, and my mom tried to defend us. She was so strong, yelling at border officials at the airport, insisting on her rights. I stayed in Kuwait for a year in middle school.

Here are me, Mama, Baba, and Baba’s cigarettes at home:

4) At 15, I became a U.S. citizen. Finally, recognition from a sovereign nation. When people talk about sending immigrants back to where they came from, I think: “Joke’s on you! I have nowhere to go back to.”

5) When I land in Kuwait, border control asks if I’ve ever resided in Kuwait. I should ask him the same thing.

Here I am with Baba and the sea at night:

6) My dad passed away when I was 27, and I didn’t understand that he was dying from so far away. I tried to rush home but was too late. I sat outside his hospital bed crying, and a Bedouin woman stared at me. She sent her son to give me a bottle of water. Two years after his burial, there was a warrant out for my dad’s arrest, since he didn’t renew his foreigner’s visa from the grave in Kuwait. It crushed my mom. My trust in bureaucracies and systems dwindles further and further.

Here is Baba’s grave in the Jafiriya Cemetery, Sulaibukhat. He is buried near my grandparents and other relatives:

7) I love the sea in Kuwait. It reminds me of my dad’s intricate knowledge of the tidal waves and seafaring culture. It reminds me of when my family was together. I think of my uncle’s passion for the sea before being killed in the war, my ancestors, my cousins, the colors, the history, and my mortality. Every time I leave Kuwait, my heart breaks into a million pieces, fully aware of the injustice that forces me to leave in waves. Again and again and again.

Here are me and my cousin Yousef, playing on the shore after Kuwait’s liberation, my cousins newly ophaned by the war:

8) Two people recently asked me: “Aren’t you worried that you’ll be the artist who’s always talking about statelessness? Don’t you want to be at peace with it?” I’m naturally inclined to feel happy as a person and have a fulfilling life in Albuquerque, but I’m angry that this is the way it had to be. Speaking about statelessness is faced with violence. It’s shameful and taboo. While I was working on the final art for my book, two stateless children as young as 10 committed suicide at the prospect of a bleak future. People are suffocating under these arbitrary policies. And while mine is a “happy” story, I’m still suffering the consequences.

The first reactions of telling people my family is from Kuwait quickly leads to talk of wealth, war, infringement on migrant workers’ rights, or — more often than not — cliché dialogues on women. Rarely though, does it bring up statelessness.

Me and my older brothers were born stateless in Kuwait, an infringement on our human rights and against international law. Stigmatized in status, being stateless means no retirement, lower wages if you can find a job, and a permanent status of “illegal resident” from birth. Until 2005, the stateless — Bidoon, those without nationality or recognition from any sovereign nation — weren’t allowed to attend universities or colleges. It’s no surprise that 40% of the Kuwaiti army is stateless, like our uncle who was killed the first day of the Iraqi invasion.

Administratively unrecognized and systematically having our rights infringed upon, we are nonetheless Kuwaiti culturally and linguistically, our family residing along the port cities of the Persian Gulf for centuries. Living a long life of oppression, our father didn’t raise us feeling neither victimized nor inferior.

This is Mama, visiting her cousins in Abadan, Iran, in the 1970’s after marrying my dad:

Unlike the Iranian, Iraqi, or other diasporas, there isn’t a large community of stateless people outside of Kuwait — or Kuwaitis living outside of Kuwait for that matter. It feels odd to be an immigrant not classified in a large group of minorities. My university once told me that I didn’t qualify as a minority, because I didn’t fit the classified minority groups. Too minority to be a minority.

I don’t feel quite Arab or Iranian. More New Mexican than American. And a mix of all at the same time. Although I haven’t been in New Mexico my entire life, people here have treated me as their equal. Giving me opportunities to grow as anyone else. Kuwait and New Mexico are both very much my homes. An enigma like a desert truffle, I’m a Kuwaiti in New Mexico.

Here I am at Barelas by the Rio Grande:

Where Butterflies Fill the Sky

We have to leave our home.”

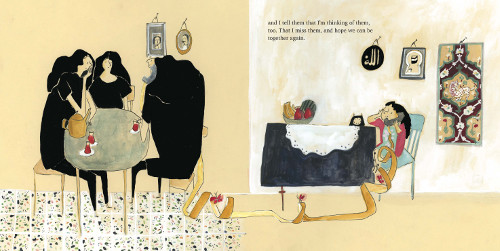

(Click spread to enlarge)

(Click spread to enlarge)

and hope we can be together again.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

WHERE BUTTERFLIES FILL THE SKY: A STORY OF IMMIGRATION, FAMILY, AND FINDING HOME. Text and illustrations copyright © 2022 by Zahra Marwan. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Children’s Books, New York.

All photos used by permission of Zahra Marwan.