Nonfiction Monday: American Icons

May 5th, 2008 by jules

May 5th, 2008 by jules

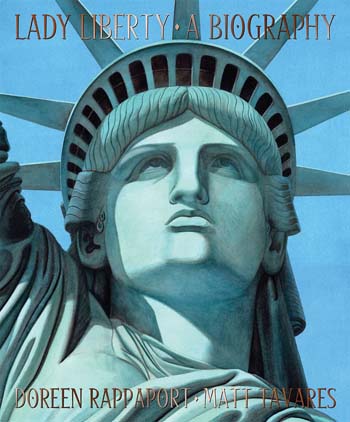

If there were any doubt to the reader that this was a biography of Lady Liberty, illustrator Matt Tavares makes it clear on the title page spread with an impressive view of Manhattan from the Statue’s eyes—a very nice touch, I must say. Yes, Doreen Rappaport brings us Lady Liberty: A Biography (Candlewick; May 13, 2008), as told from the perspective of everyone from the engineers to the sculptor to those who wrote poetry in her honor to those who gathered nickels and pennies—and farm fowl—to help fund her.

If there were any doubt to the reader that this was a biography of Lady Liberty, illustrator Matt Tavares makes it clear on the title page spread with an impressive view of Manhattan from the Statue’s eyes—a very nice touch, I must say. Yes, Doreen Rappaport brings us Lady Liberty: A Biography (Candlewick; May 13, 2008), as told from the perspective of everyone from the engineers to the sculptor to those who wrote poetry in her honor to those who gathered nickels and pennies—and farm fowl—to help fund her.

In the opening spread—the author’s own musings on her grandfather’s journey one hundred and twenty years ago from Latvia to the United States and what it must have felt like for him to see Lady Liberty in the harbor—Tavares brings to life the boat of Rappaport’s grandfather, “a ship packed with people from many different countries . . . and there was Lady Liberty greeting them all . . . People lifted babies so they could see her. Tears ran down my grandfather’s face. People around him were crying, too. And then a wave of cheering and hugging swept over the ship.” And, in another nice touch, Tavares paints the present-day Rappaport in the picture as well, standing above the immigrants and also looking reverently at the statue. Such a lovely, affecting spread, knowing she is standing above her own grandfather, perhaps even the one lifting his arms out toward the statue.

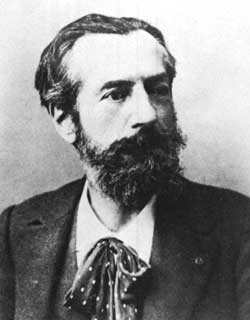

Rappaport then delves into the history of the creation of Lady Liberty, alternating the points-of-view of all those involved — from Édouard René Lefebvre de Laboulaye, professor of law, who first suggested “a monument from our people to {America’s} to celebrate their one hundred years of independence and to honor one hundred years of friendship between our countries”; to Auguste Bartholdi {pictured here}, Lady Liberty’s sculptor; to Marie Simon, his assistant; to Gustave Eiffel, the structural engineer. But Rappaport delves deeper, giving us, arguably, the most impressive spread — Emma Lazarus’ perspective on the monument (“Soon when people arrive in the New World, they will be welcomed by a caring, powerful woman”). We also see the construction of Lady Liberty from the eyes of a construction supervisor (speaking of the workers, he says,

Rappaport then delves into the history of the creation of Lady Liberty, alternating the points-of-view of all those involved — from Édouard René Lefebvre de Laboulaye, professor of law, who first suggested “a monument from our people to {America’s} to celebrate their one hundred years of independence and to honor one hundred years of friendship between our countries”; to Auguste Bartholdi {pictured here}, Lady Liberty’s sculptor; to Marie Simon, his assistant; to Gustave Eiffel, the structural engineer. But Rappaport delves deeper, giving us, arguably, the most impressive spread — Emma Lazarus’ perspective on the monument (“Soon when people arrive in the New World, they will be welcomed by a caring, powerful woman”). We also see the construction of Lady Liberty from the eyes of a construction supervisor (speaking of the workers, he says,

“{w}hen the sun goes down, they eat, then stumble off to sleep in makeshift tents on the island. But I believe they are content, for they are building new lives in this country”) and from the perspective of New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer, who asked his readers to help fund the monument’s completion, once it became clear that more money was needed to build her pedestal, yet “{t}he mayor of New York City does not want her. Congress has refused to give money for her pedestal. I cannot understand why politicians do not understand her power as a symbol of freedom.” And, rounding out the impact of Lady Liberty’s birth on various socioeconomic classes of people in the States, Rappaport includes a spread devoted to a young farm girl, who sends two pet roosters in Pulitzer’s campaign to raise money for the pedestal. Rappaport’s Author’s Note, all about her research for the writing of this biography, explains how she found a letter—while searching in the New York World—written by this girl, Florence de Foreest: “After reading these accounts, I felt as if I knew these people. I decided that they should tell the life story of the Statue of Liberty. Their comments, experiences, and feelings are woven into my text.” And it’s very effective, indeed, showing the impact this symbol of freedom had on, not just those who sweated to create her, but those who were inspired by her and contributed to her creation.

One of the final spreads—which folds out vertically on one side into a breathtaking (even if you’re not terrified of huge stone monuments, as I am) view of Lady Liberty on the rainy day of her unveiling on October 28, 1886—is told from the perspective of Bartholdi, the sculptor. This excerpt (though you’ll note some ellipses) gives a taste of the poetic prose (“poetic vignettes,” the publisher calls it) Rappaport puts to use to tell the statue’s story, prose spun in a sparse and uncluttered manner:

Liberty’s face is hidden beneath our tricolors.

I see easily through to her magnificence . . .I crouch to look through her windows.

I wave to the boy below who will signal me

at just the right moment . . .

Cannons fire deafening salutes.Finally quiet. A blessing.

One speech. A second speech.

I cannot hear anything over the shrieking tugboats.The boy waves his hand.

At last, it is time.

I loosen the cord holding the tricolors

over Liberty’s face.

The final spread brings us full-circle to the author—present-day once again—staring up at the statue. A page listing the statue’s dimensions, a page listing Important Events, and Selected Sources for more information are also included.

As for Tavare’s stunning illustrations—rendered in watercolor, ink, and pencil—Rappaport puts it best in her Author’s Note: “I am grateful to my illustrator, Matt Tavares, for his exceptional commitment to detail, along with his striking artistic conception.” As already mentioned, several of these spreads will take your breath away; there is great intensity, reverence, and detail in these images, and Tavares clearly did his homework, bringing to vivid life the world of the statue’s birth — on both sides of the pond.

An impressive biography, showing how the visions and hopes and sweat of many—including many immigrants to the States—gave birth to one of the world’s most iconic statues.

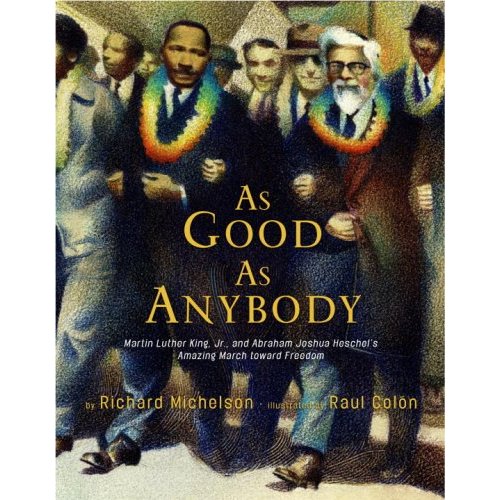

Raise your hand if you love Raúl Colón’s work as an illustrator? Wait, I can’t see you all, so I’m going to have to trust someone else out there ooooh! ooooh!s a lot, as I do whenever I see he has a new book out. This one, Richard Michelson’s and Colón’s As Good As Anybody: Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Amazing March Toward Freedom—also to be released next week on the 13th (Alfred A. Knopf)—is a beautiful tribute to the determination and passion of these two men and how they joined forces with the same message of equality for the American people—despite having different upbringings.

Raise your hand if you love Raúl Colón’s work as an illustrator? Wait, I can’t see you all, so I’m going to have to trust someone else out there ooooh! ooooh!s a lot, as I do whenever I see he has a new book out. This one, Richard Michelson’s and Colón’s As Good As Anybody: Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Amazing March Toward Freedom—also to be released next week on the 13th (Alfred A. Knopf)—is a beautiful tribute to the determination and passion of these two men and how they joined forces with the same message of equality for the American people—despite having different upbringings.

And it has quite the memorable opening: “Martin was mad at everyone.” That sentence gets its own spread, and pictured, in Colón’s radiant, soft-focus style (the illustrations rendered in colored pencil and watercolors), is a young Martin Luther King Jr. He’s seated in front of the closed entrance to a pool: “WHITES ONLY,” the sign says. Constantly being faced with such signs, his anger grows: Colón shows us a defiant, heavy-hearted King. “He marched to his father’s church and stomped his feet. ‘What good is stepping on bugs?’ Daddy King said. ‘You’re looking down when you should be looking up.'” In one spread, his mother comforts him: “‘Some ignorant white people think they are better than colored people,’ she said, hugging Martin close. ‘But don’t you ever forget you are just as good as anybody!'” Michelson then jumps ahead many years to King’s adult years as a minister and social rights activist (and I must say that those looking for an impressive, spot-on likeness in their picture book depictions of famous protagonists will not be disappointed with Colón’s depiction of King. It’s uncanny. He nails King’s features, and he almost leaps off the page.)

In the final spread, towards the book’s middle and before we switch to Heschel’s upbringing, King is organizing his protest march from Selma to Montgomery. “A man named Abraham answered Martin’s call,” Michelson writes, thus launching us into Heschel’s childhood in Warsaw, all the while emphasizing the elements of his childhood that were similar to King’s — a rabbi for a father, a calling to the ministry himself, oppression and harrassment from another group of people (in Heschel’s case, the Nazis, of course), and his own mother’s pleas for peace: “His mother threw her arms around him. ‘Perhaps in the next world, people everywhere will live together in peace,’ she cried. Abraham held her close. He could feel how thin she had become. He didn’t want to wait for the next world. He wish he could help her now.”

After Abraham heads to the U.S. (“Abraham rejoiced to see the Statue of Liberty” in a lovely Lady of Liberty spread), his family died after Hitler invaded Poland — Michelson, fortunately, not diminishing that particular horror of the war for the child reader. Abraham then marched all over America, speaking of peace, as King was doing. The book closes with his determination to answer Martin’s call:

On March 21, 1965, in Selma, Alabama, Abraham Joshua Heschel and Martin Luther King Jr. prayed together. Then Martin stomped his feet and Abraham stomped beside him.

The time had come for action. The white man and the black man joined hands. The Jew and the Christian joined hands. Three thousand people stood behind them, cheering.

There were not enough police in the state to hold the marchers back. There were not enough mayors and governors and judges to stop them.

And, well, I’m dying to tell you about the final spread, as I found it very moving and quite beautiful—both the writing and illustration (which I guess I’ll cheat and tell you is also the cover)—but that seems somehow unfair to do. Just go pick this up yourself and see. It’s a powerful, stirring tribute to two of America’s most prominent civil rights leaders and to justice and equality. And I don’t even have to tell you of the innumerable ways this book can be used in school libraries and classrooms. Highly recommended.

And, well, I’m dying to tell you about the final spread, as I found it very moving and quite beautiful—both the writing and illustration (which I guess I’ll cheat and tell you is also the cover)—but that seems somehow unfair to do. Just go pick this up yourself and see. It’s a powerful, stirring tribute to two of America’s most prominent civil rights leaders and to justice and equality. And I don’t even have to tell you of the innumerable ways this book can be used in school libraries and classrooms. Highly recommended.

Until next Nonfiction Monday . . .

Jules,

I, too, am a big fan of Colon’s work. I really liked his illustrations for Jonah Winter’s ROBERTO CLEMENTE: PRIDE OF THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES.

Thanks for the two great reviews!

[…] Made) 5. The Well-Read Child (Surfer of the Century) 6. Julie M. Prince (As Good as Anybody) 7. Jules, 7-Imp (Lady Liberty’s biography and new PB about King and Heschel) 8. Lori Calabrese Writes (I Could Do That! Esther Morris Gets Women the Vote) 9. Becky: Dickens: […]

[…] Seven Impossible Things Before BreakfastYA and Kids Book CentralI.N.K. (Interesting Nonfiction for Kids) […]

[…] at the book’s close with subtlety. Tavares brought us Lady Liberty last year in this gorgeous book. He doesn’t disappoint and, it seems, gets better with each […]

[…] one illustrator I go to is Matt. In writing about his illustrations for Doreen Rappaport’s Lady Liberty, James McMullan wrote in The New York Times, “Tavares creates images with a pageantlike […]