My Conversation With Brian Selznick:

On Wonderstruck, Hugo, and the

Terror and Joy of Creating Books

October 27th, 2011 by jules

October 27th, 2011 by jules

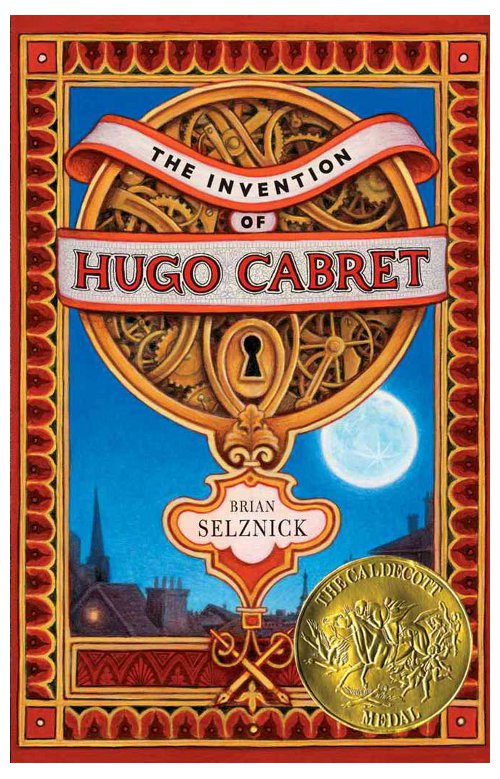

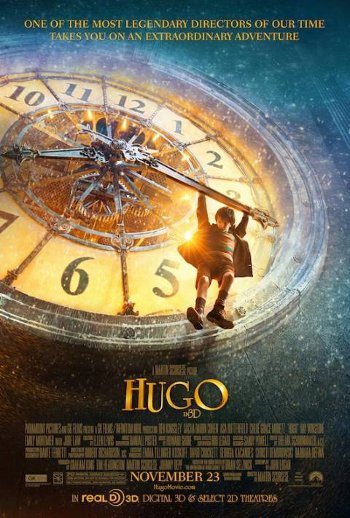

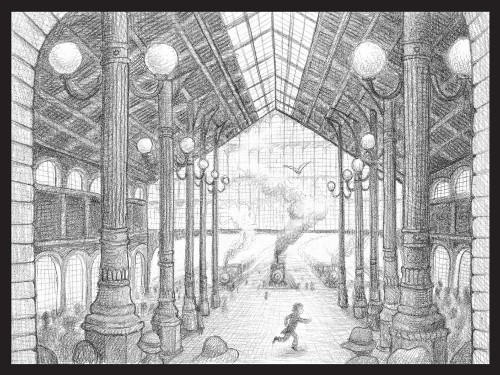

I had the pleasure in early September of talking via phone with author/illustrator Brian Selznick about his latest title, Wonderstruck (Scholastic, September 2011), as well as a bit about the 2008 Caldecott winner The Invention of Hugo Cabret (Scholastic, 2007); his hybrid style, if you will, of picture book, novel, and graphic novel; and the upcoming film adaptation of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, titled simply Hugo, by Martin Scorsese.

I had the pleasure in early September of talking via phone with author/illustrator Brian Selznick about his latest title, Wonderstruck (Scholastic, September 2011), as well as a bit about the 2008 Caldecott winner The Invention of Hugo Cabret (Scholastic, 2007); his hybrid style, if you will, of picture book, novel, and graphic novel; and the upcoming film adaptation of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, titled simply Hugo, by Martin Scorsese.

7-Imp readers know that my interviews, particularly with illustrators, tend to consist of the same set of questions I send to everyone — and interviews I can conduct via email, too. If, in Bizarro World, 7-Imp’ing were a full-time venture, everyone would get questions customized specifically to them, but having a standard set of questions for all the folks with whom I conduct Q&As is the only way I can find time to post any interviews at all, since blogging comes after things like children and work.

However, with Selznick I had the opportunity to do a phone interview right at the release of Wonderstruck and didn’t want to pass it up. But it took a while to post, since after the interview’s completion, I had to find a transcriber to make it so that I could post it online for my readers. Finally, nearly two months later, here it is.

In a former professional life, I was a sign language interpreter. My Bachelor’s degree is actually in that very subject, and I spent years studying American Sign Language and Deaf Studies and worked in the field for a good while in East Tennessee. For that reason, several of the questions below—and a good deal of my conversation with Brian—is about his research into Wonderstruck and the deafness aspect of the novel, which I wrote about over in a September Kirkus column. That link is here.

Also, I should quickly note two things: First, my landline phone, during our conversation, decided it’d had enough of me, and when I called Brian back on my cell, he and his editor ever-so kindly recorded the latter part of the conversation on their end. This meant that my final questions and comments were not recorded, but as you can see below, I was able to piece together what I had asked him. Secondly, the transcriber did edit out things like “um”s—my own and Brian’s—but we generally left intact the casual, conversational tone that was this phone interview.

I thank Brian for his time. Fellow illustration junkies will note that I’ve laced the interview with a bit of art, with thanks to Brian and Scholastic. Enjoy.

Jules: You wrote in the close of Wonderstruck, in your acknowledgements, that you knew at a really early date that you wanted your protagonist to be deaf, and you talk about your research. But I wondered what made you decide, to begin with, that you wanted the character to be deaf.

Brian: It actually grew out of a couple of things, including the fact that I, for the first time, came up with the structure for my book before I came up with the content. Usually, the content leads the structure — you know, I was writing the story of Hugo about a boy in the movies, and I decided to try to tell the story like a movie and took out words and came up with the idea of the picture narratives. But when it was time to start working on my next book after Hugo, I was thinking about what I could do to sort of adapt what I had learned about making a book from Hugo. I didn’t want to repeat myself exactly, but I really loved what I learned in terms of telling a story with pictures and going back and forth with the text.

Brian: It actually grew out of a couple of things, including the fact that I, for the first time, came up with the structure for my book before I came up with the content. Usually, the content leads the structure — you know, I was writing the story of Hugo about a boy in the movies, and I decided to try to tell the story like a movie and took out words and came up with the idea of the picture narratives. But when it was time to start working on my next book after Hugo, I was thinking about what I could do to sort of adapt what I had learned about making a book from Hugo. I didn’t want to repeat myself exactly, but I really loved what I learned in terms of telling a story with pictures and going back and forth with the text.

And I happened to see a puppet show that a friend of mine did. My friend, Dan Hurlin, is a puppet artist and a theatre director, and he did a show called Hiroshima Maiden, which told two different stories. One was the story of a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima, and her story was told with no words, and it was entirely done with bunraku puppetry, which is a Japanese style of puppetry that takes three people to perform. That story was interspersed with a narrative that was told completely in text—about a boy growing up in New Hampshire—that seemed completely unrelated to the other story. And that narrative was told by a Japanese storyteller sitting on the opposite side of the stage. And these two narratives went back and forth until they came together in the end in a very surprising way.

And so, I thought, well, maybe that’s what I should do with the words and the pictures from Hugo. Maybe I can separate the picture story and the word story and try to tell two different narratives and have them weave together and then come together at the end. But I didn’t know what story would justify that structure, because I always feel like the structure of the book has to illuminate the story that it is telling in some way.

I remembered a documentary that I saw on TV, while making The Invention of Hugo Cabaret, called Through Deaf Eyes, which you might be familiar with. It’s about the history of Deaf culture—it was narrated by Stockard Channing—and there were a couple of things in it that, when I watched it, really caught my attention. One was an interview with a young deaf man who grew up with hearing parents, and his parents were great. They learned sign language, they taught him sign language, but it wasn’t until he went to college and met other D/deaf people that he realized that he was actually part of a culture that has a history and [that] there is a community with this unique language. And that was something that really stuck with me, because I think so many of us grow up and then find that it is people outside of our biological family who, in a way, create a community that we feel at home in.

I remembered a documentary that I saw on TV, while making The Invention of Hugo Cabaret, called Through Deaf Eyes, which you might be familiar with. It’s about the history of Deaf culture—it was narrated by Stockard Channing—and there were a couple of things in it that, when I watched it, really caught my attention. One was an interview with a young deaf man who grew up with hearing parents, and his parents were great. They learned sign language, they taught him sign language, but it wasn’t until he went to college and met other D/deaf people that he realized that he was actually part of a culture that has a history and [that] there is a community with this unique language. And that was something that really stuck with me, because I think so many of us grow up and then find that it is people outside of our biological family who, in a way, create a community that we feel at home in.

There was also a section about the transition to sound from silent movies, and because I was working on Hugo at the time, that caught my attention. And they talked about how before sound, deaf people were able to enjoy movies, which was the main form of popular entertainment, along with hearing audiences. But, when sound came in, it separated out the deaf audience, and it was described in the documentary as a tragedy for the deaf community. And, as a hearing person, that was something that had never crossed my mind. And then there was a quote from an educator, who said that the “deaf are a people of the eye,” and I took that to mean that because sign language is a visual language, it’s a language that you watch, that you look at to communicate, that much of the way D/deaf people communicate is through what they see.

And suddenly, all of these ideas were rolling around in my head, and I realized that that might be the perfect reason to tell a story entirely with pictures. And the idea of trying to tell the story of a deaf character in a way that might somehow echo her experience, as she moves through her world, seemed like a really exciting thing to experiment with.

Jules: I guess I wondered if you had met a D/deaf person and heard about these things personally through him or her. I know for your research, which you described in the acknowledgements, you talked to a lot of members of the Deaf community.

Brian: My first experience with anything having to do with Deaf culture was Remy Charlip’s book Handtalk, which I had when I was a kid. From that book I learned to fingerspell the alphabet and always loved to fingerspell my name, and you know, as a hearing kid it feels like you’re learning a secret code. And so that always stuck with me, and Remy Charlip made a lot of my favorite books when I was a kid. I went to camp with someone who was deaf, and I remember communicating with Mike, but he was able to read lips, and we did a lot of gestural work to get our ideas and activities across.

Brian: My first experience with anything having to do with Deaf culture was Remy Charlip’s book Handtalk, which I had when I was a kid. From that book I learned to fingerspell the alphabet and always loved to fingerspell my name, and you know, as a hearing kid it feels like you’re learning a secret code. And so that always stuck with me, and Remy Charlip made a lot of my favorite books when I was a kid. I went to camp with someone who was deaf, and I remember communicating with Mike, but he was able to read lips, and we did a lot of gestural work to get our ideas and activities across.

Jules: As a child, I didn’t know any people who were deaf, but I used to see deaf people sign while out and about and thought it was the most eloquent, beautiful language. I also thought that there must be some sort of secret code to it, as you put it, and I remember following them in, say, stores and trying to mimic their signs. I look back now and hope I didn’t look disrespectful …. I mean, at a very young age, it struck me what a gorgeous language it is.

One thing I was curious about: Did you decide to learn the language at all? As I learned American Sign Language and studied ASL and Deaf Studies [as the socio-linguistic study it is] in college, I was struck by how complicated it is. It’s a very difficult language, and what’s ironic is that I think the average person on the street thinks that, you know, you’re just signing word-for-word what the English language says, that it’s simple. And that probably stems from, like, in [hearing] elementary schools you’ll have teachers who teach things, like “A is for apple, and B is for ball,” and that is where they tend to stop. I think that there’s this perception that it’s easy. And, I swear, it has to be one of the most complicated languages to learn!

Brian: I know. Most hearing people don’t know that it has its own grammar…and there are things that are in common with English, but it is definitely its own distinct language. And I think also many hearing people are surprised to discover that sign language isn’t universal, because there are not any spoken words, so people think that everybody must be able to understand it, who speak it all over the world. But there are different dialects. You know, within American Sign Language there are different dialects and slang words … and one of the keys to me understanding anything about the Deaf community comes from the fact that my boyfriend, David Serlin, is a professor at The University of California at San Diego, and two of his colleagues happen to be two of the world’s leading scholars of Deaf history and linguistics, Carol Padden and Tom Humphries.

So, we’ve been friends with Carol and Tom, and I’ve known them, and when I started working on this, I approached them about possibly helping me a bit with this book — to make sure that what I’m writing about is accurate, because there are all different kinds of accuracies. There is historical accuracy, but there is also emotional and experiential accuracy — to make sure that what’s happening to my characters feels authentic to someone who actually is D/deaf … [M]yself, not being deaf, the best I can do is read extensively. You know, I read so many books about people who are deaf, people whose children became deaf, people whose parents were deaf—any situation—the history of Deaf culture. I read many of Carol and Tom’s books, and I did interview several people who are deaf. And it was really Carol and Tom’s close reading of everything that I did and the incredible conversations that we had about the world that I was creating, the people that I was trying to make up, and the things that I was having happen to them that really helped me make this story. I always feel like if there is anything in the book that seems accurate, it’s because of Carol and Tom.

One of the challenges … You know, in a way, it was easy to get the historical stuff accurate, because those are facts, and so certain things happened at a certain date, people were treated a certain way at a certain time, schools were a certain way, jobs for deaf people, there were certain jobs at certain times … But in a way it was much harder to try to get into the head of my characters and to figure out what they were experiencing, because … There is Rose, who is born deaf, but because her story is told in pictures, the reader, who doesn’t know anything about the book, won’t even know that she is deaf for the first third of the entire novel. So, there were certain things that I had to figure out that happened to her that are actions. Because when you are drawing, you can really only draw actions. There is some text that we read within her story, where she writes notes, she reads books, she reads newspapers that we also read, but most of her story is told through action.

But Ben is a character who becomes deaf during the course of the story. So, he identifies as a hearing person, even though he was born deaf in one ear. I had originally wanted him to have hearing in both ears, and I knew I wanted him to become deaf from a lightning strike, because the other thing I had before the plot was the title of my book. I wanted to write a book called Wonderstruck, and I didn’t know what it was going to be about. I just had this idea that it was a really good title, and it was a word that I used in my very first book, The Houdini Box, in 1991. And so I thought that it would be a good title. I just didn’t have a plot or characters. As I was developing it, I thought, well, if you’re going to have a book called Wonderstruck, you have to strike someone with something, and so I really wanted to hit this kid with lightning. And I wanted him to be on the phone and the lightning to come through the phone. And I wanted him to go deaf in both ears.

But Ben is a character who becomes deaf during the course of the story. So, he identifies as a hearing person, even though he was born deaf in one ear. I had originally wanted him to have hearing in both ears, and I knew I wanted him to become deaf from a lightning strike, because the other thing I had before the plot was the title of my book. I wanted to write a book called Wonderstruck, and I didn’t know what it was going to be about. I just had this idea that it was a really good title, and it was a word that I used in my very first book, The Houdini Box, in 1991. And so I thought that it would be a good title. I just didn’t have a plot or characters. As I was developing it, I thought, well, if you’re going to have a book called Wonderstruck, you have to strike someone with something, and so I really wanted to hit this kid with lightning. And I wanted him to be on the phone and the lightning to come through the phone. And I wanted him to go deaf in both ears.

I got into contact with Dr. Marilyn Cooper, who is one of the country’s leading lightning strike injury experts …

Jules: Oh! There is such a thing?

Brian: Yes. And she was also very generous with her time. And she said that there was no way that someone could become deaf in both ears from a lightning strike through the phone. You would go deaf in the ear that you are holding the phone to, but the only way you could go deaf in both ears is if you’re already deaf in the other ear.

My brother was born deaf in one ear, and he does not identify as D/deaf in any way. He had a hearing aid for a little while, as a kid, but they quickly realized that there were no bones or anything in his inner ear, so it wasn’t actually doing anything, so he just learned to sit on the right side of the class room and to turn his head and to, you know, completely identify as a hearing person. It’s funny, because my boyfriend has a friend who grew up also deaf in one ear, and she completely identifies as part of the Deaf community and she knows sign language. So, it was really fascinating to me how these two people with the same condition sort of created their own identities as they grew up.

Ben became deaf in one ear, and I interviewed my brother and asked him a little bit about what it was like, because my memory as his older brother was really just making fun of him about it. I would say, all the time, just like Ben’s mean cousin Robby says, “What are you, deaf?” whenever he didn’t hear me. He laughed, because he had a very good sense of humor and we really liked each other, so I wasn’t being mean the way Robby is in the book. … But Lee gave me some really interesting insights about how he could put his hand over his good ear in class to block out the sound, or he could sleep on his good ear so that it was very quiet. Those were things that I hadn’t known about or thought of, and so I gave those qualities to Ben. I also asked Lee if he ever worried about losing the hearing in his other ear, and he said, in fact, he did — which is, again, something I didn’t know about, so I was able to give all of those qualities to Ben.

So, yes, it was really fascinating learning about all of this, and the most difficult part was figuring out what is true to the “Deaf experience.” Like, what is something that a deaf person would read about and say, “Oh that’s what my life is like, or that’s how I feel,” and what is something that’s specific to the characters that I’m making up in this plot that I’m making up — in a sense and a way that’s something that’s never happened before? So, I had to make sure that it both felt true to the experience of someone who really was D/deaf, but I also wanted to make sure that I was serving the narrative and my specific characters, as much as possible.

One of the most interesting moments in my conversations with Carol and Tom came around the moment at the end of the book, where there are characters that have to communicate, who are deaf, but one doesn’t sign but can still speak. One can’t speak but can sign, and then another character who can speak and sign. And I was writing these scenes where all of these characters have to figure out how to communicate. So, of course, for me as a hearing person, it just seemed like writing would be the most logical way for everyone to communicate, and of course writing is something that people who are deaf will use to communicate with people who are hearing. Bu I just decided that that was going to be the only way that everybody communicated — that as soon as everyone found out about everyone else’s communication issues, that for the rest of the book, everyone is just going to write. …

And early on, Carol and Tom said to me that, in fact, that is not the way anybody would really communicate — that if one character can still talk but he is deaf, he would talk to the hearing person, and then the hearing person, if they are answering in a simple way, could have their lips read by the person who isn’t trained to read lips, but then if they want to say something more, they could use some gestures, they could do some lip reading, and they could do a little bit of writing.

So, all of the sudden, I had to go back and in one conversation have a character talk, a character lip read, a character speak, and a character gesture — all to get across a single conversation. And then at the very end, there is a part where one character has to communicate a lot of information to another character, and they don’t have sign language in common, and they can’t speak to each other. And so I decided that the character would write a very, very long entry in a notebook, and the other character would read it. And when Carol read this, she said, “Brian, this is very unrealistic. A deaf person would never write for twenty pages. That’s just too much.”

So, I got that email, and I panicked, because I thought, how else is she going to get across all of this information, because it’s a lot of information that has to be communicated. I had a little bit of a panic, and a couple of days later I got another email from Carol, and she said that she had been thinking about this, and she remembered a time when she was younger, when a hearing uncle came to her house. Carol grew up in a deaf household with deaf parents and deaf grandparents on the campus of Gallaudet. She grew up where deafness was completely normalized.

Jules: She’s hearing, right?

Brian: She is not hearing—she is deaf herself—but she is really great at lip reading, and she can speak. It’s very easy for a hearing person to communicate directly with her in person, as well.

So, she said that she remembered when she was young that a hearing uncle came to her house. And her mother, who was deaf, wanted to tell him a very long family story, and they sat at the kitchen table all afternoon, and the mother wrote and wrote and wrote all afternoon. In a way, that gave me a kind of psychic permission to keep the end of the book the way I wanted it to be. But it was a really scary moment, because if I hadn’t gotten that email, I might have had to keep it anyway, but I would have felt much worse not knowing — or being afraid that it might not come off as realistic.

And, of course, there are lots of other people who might read it and have had different experiences and feel like something is realistic that Carol doesn’t [feel is realistic] or vice versa. It’s not like any one person speaks for the entire community, but it was really helpful to know that for Carol, who had been a really helpful voice in this project, it was something that rang as true.

Jules: I think it’s well-handled, given the fact that, like you just said, there is not one person that speaks for everyone and the fact that your brother grew up deaf in one ear and totally felt part of the hearing community, and then you have your boyfriend’s friend, who in the same boat, who felt a part of the Deaf community. So, it all comes down to the individual.

I’m curious: Given all the research, how many years total did you work on this book?

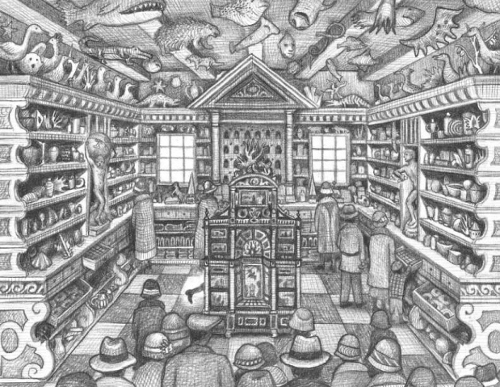

Brian: I worked on it for about three years, but there were some elements of the book that started a long time before that. A friend of mine worked at the Museum of Natural History back in the early 1990s, and he brought me to the museum to go backstage and to see the workshops where he makes the displays and paints. And it was back then that I thought it would be interesting to set a story behind the scenes at the Museum of Natural History. So, there are elements that, you know, go back much, much further, including Remy Charlip’s Handtalk, to when I was a kid.

Jules: So, I love the drawings in the book. They are really, really gorgeous …

Brian: Thank you.

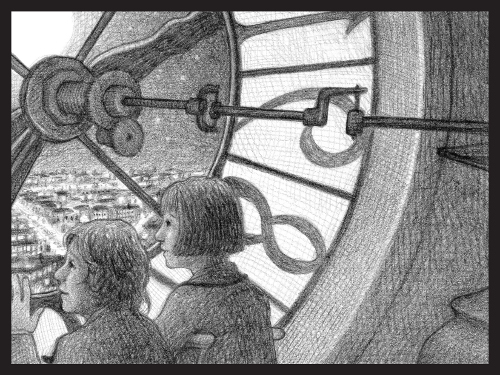

Jules: …and I found myself wondering if you use models for your work — for this and for Hugo, as well.

Brian: Yes. I start all of my drawings as little tiny thumbnail sketches with little one-inch by one-inch pictures. And I make up everybody from my head, and I start looking in the world for people who look like the characters whom I’ve made up, and then I ask them to pose for me. You know, there are real versions of everybody in Wonderstruck, and after I ask everybody to pose for me, I bring them the drawings that I’ve done and have them pose in the positions that I have sketched for the characters.

A lot of times I actually draw positions that human beings can’t really get into, and so I have to take, like, three or four different pictures to approximate the pose, because in the drawings they look like they are poses that a human being can do, but you might notice, if you try to do some of them, that your feet might not work that way or your arm might go a different way. But I need them to be in that position for the drawing, so I take lots and lots of photographs.

The girl who posed for Rose is named Sophia, and she lives in San Diego with her family, and I met her one evening with her folks at the theatre. The two boys, who play Ben and Jamie, were two boys who interviewed me after a Los Angeles school visit that I did, and I contacted the librarian and asked her if she could track down the kids and their parents and put us in touch. It’s always an interesting moment when you can first introduce yourself and say, you know, hi, I’d like to draw your kids and see if they look like characters I’ve made up. Luckily, for Wonderstruck, by coincidence, everyone had already read The Invention of Hugo Cabret, so they knew who I was, they liked my books, and they were excited about being part of the next one.

Jules: I wondered, as I read, how challenging it was—if at all—to construct the words and the art in such a way that the puzzle of the story isn’t revealed until the end — and the connection between them.

Brian: Yeah, it was very, very difficult, and I didn’t even know really how everything was going to work together when I started out, but I began by writing an outline of both stories. So, even though I knew that Rose’s story was going to be pictures, I still started it as a written outline. Once I had the basic outline of the two stories, I began making Ben’s story more complex and filling it out in prose. And I started trying to figure out how to tell Rose’s story with pictures exactly.

Then, as I was developing both of the stories, it would change what was happening in the other story. So, for instance, I knew that I wanted to have Ben get struck by lightning, as I said, and I really wanted to draw lightning. But, because Ben’s story is told entirely with words, I couldn’t draw anything from his story. I couldn’t draw lightning, but then I thought, oh, I can draw lightning in Rose’s story, and so I came up with the idea of having Rose go to a movie theater in 1927 and see a movie, where there is lightning on the screen. I liked that idea, but then I needed to have a reason for her to go to a movie theater. Then I thought, well, maybe there is an actress in this movie whom she really likes. I made up the actress Lillian Mayhew, and then I began to realize that, if that was going to work, I had to have more of a reason about why she is obsessed with this actress and what she’s doing there and why she’s following her, and so suddenly her relationship with Lillian Mayhew became a central part of her narrative.

And all of that developed because I wanted to draw lightning for Ben.

Jules: What specifically made you want to work in this format again – your hybrid, if you will, of picture book, novel, and graphic novel? [And it was at this point, dear readers, that my phone told me that my story had become tiresome and went kaput, but I think I also asked him here if he felt any pressure writing Wonderstruck, given the success and similar format of Hugo.]

Brian: When I developed the structure for Hugo, I was really excited about what I learned, in terms of how to illustrate a book and thinking about what pictures can do narratively in stories for older readers…. And, before Hugo was published, I had no idea if it was going to be a success. I didn’t know if anyone was going to read it, but I was very proud of the fact that I got to a point before publication where I feel like I made the book I wanted to make. I pushed myself, I did something I’d never done before, and I made something that I thought was challenging and interesting, and so I felt satisfied in that.

Of course, the 2½ years it took me to make Hugo, I felt like I was making something that was going to be a giant failure and that it wasn’t going to work and the narrative wasn’t going to come together, and people weren’t going to be able to read it … like, it was 2½ years of terror, but I came to the point where I liked what I had done.

So, then to my great surprise, this book about French silent movies for children turned out to be a huge success, and I got to travel around the world as the book was published in many different countries and speak to kids about making the book and the words and the pictures. And one of the things that the kids always talked about was how much they loved the way the pictures told part of the story. Younger kids were excited about the fact that they could carry around a 530-page novel that they could read themselves. I loved that teachers were telling me that it was being used in both remedial classes for kids who have trouble reading and advanced readers’ classes at the same time, which I thought was fantastic.

And so, by the time my traveling for Hugo came to an end and it was time for me to start work on the next book, I was aware of the fact that the great success of Hugo was going to have an impact on the way people looked at my next book, whatever it was.

When I made Hugo, I had a very good career before it, but nobody was looking forward to Hugo. Hugo kind of built its own momentum, once people heard about it and saw what it was. But with Wonderstruck, most people, amazingly, now know Hugo, and I knew that they would want to see what it was that might come next. So, I certainly was aware that there was going to be a kind of pressure on the next book that was not there for Hugo, and I can say that there was also a certain worry that came along with that.

But when it was time for me to actually sit down at my desk with the blank piece of paper and the computer and my pencil and eraser, I can honestly say that the only thing that mattered was what this story was going to be. Again, it was three years of terror, but it was the same terror I had experienced making Hugo, and it’s the terror of trying to get everything right for the book. It’s the terror of not knowing if it’s going to come together. But the terror, of course, is made palatable by the fact that I’m doing something that I love, and I’m writing about things that I love, and I’m creating characters that I love, and I’m getting to research topics that I’m fascinated by. So, there is that love that carries you through it, but there is the real fear that it’s not going to come together.

And I think a lot of people thought that, because of the success of Hugo, I knew that my next book would of course be a big success. I can say that that could not be further from the truth. I thought, well, of course no one is going to like anything I do after Hugo, because they liked Hugo so much, and in a way that kind of freed me up to just forget about it and work on the book. I was, like, you know what, I’ve already made Hugo, I’ve had this incredible success that I’m so grateful for, I’ve been making books for a really long time, and most people never experience anything like this. And so whatever I do now, it’s, like, okay, I’m going to do it for myself. But, in fact, that’s exactly how I made Hugo. So, I spent the three years working as hard on Wonderstruck as I did on Hugo.

And, in fact, while I was working on it, I used to joke with my editor that it feels even harder than Hugo, because in a way we are making three different books at the same time. We’re making a book that has to work just as a picture narrative, so if you start at the beginning and just read the pictures from front to end, for three quarters of it, it will make perfect sense by itself. Then, I had to write a story that takes place just in words, so if you read just the word story from front to back, most of it will make sense on its own. But then, I was creating the book that happens when those two stories intersect, and that becomes a whole new element. Because of things like the lightning in both stories that are taking place for different reasons, you as the reader are constantly being asked to imagine something from one story illuminating something in the other story. So, for instance, we find out that both kids are deaf at the same moment. Ben becomes deaf at the moment that we discover in the narrative that Rose has been deaf all along. So, as we read about Ben’s feelings regarding his deafness, we can imagine that some of those feelings might also pertain to things that Rose has experienced. So, you are being asked to put things together in your mind and to make a new book, in a way, in your head, as you are reading it.

Whenever things were going really slowly, we would laugh about the fact that, well, it takes a long time to make three books.

Jules: [Again, this is the part of the conversation in which my questions weren’t recorded, so I’m not exactly sure what I said here to Brian, though surely it was erudite, witty, and sophisticated. No, seriously, I believe I commented about how Rose’s narrative is visual … Well, as I wrote in my Kirkus column, “this is a story in which Selznick’s groundbreaking format is even more fitting. Since American Sign Language is a complex visual language (and brilliant, I might add, though I’m a bit biased here), uniquely structured to meet the needs of the eyes, it is fitting that in the hands of Selznick we have someone who creates such sophisticated and eloquent wordless spreads.” Yes, I believe I made a comment here in our phone conversation about precisely that, as our conversation began to wind down.]

Brian: Because so much of the book is about how we communicate, that became not only part of the plot, but also so much in the structure and what we see. And, you know, in the end, when I finished Wonderstruck, I got to the same point I did with Hugo, which is that I looked at what I did, I felt like it was different than Hugo, but I had taken everything I’d learned from Hugo and did something new with it. And I had no idea what people would make of it, but I knew that because I felt about it the same way that I felt about Hugo that I would be okay — and that the book itself might possibly be okay in the end.

Jules: Perhaps you’ve discussed this in previous interviews, so feel free to skip this, but have you seen the film adaptation of Hugo Cabret yet [to be released on November 23]? How involved, if at all, were you in the creation of the screenplay, etc.?

Jules: Perhaps you’ve discussed this in previous interviews, so feel free to skip this, but have you seen the film adaptation of Hugo Cabret yet [to be released on November 23]? How involved, if at all, were you in the creation of the screenplay, etc.?

Brian: John Logan, who has worked with Scorsese before and has written some really wonderful screenplays, wrote the screenplay, and I got to read a couple of the drafts, and so that was really exciting to watch it, as it developed.

But really everybody used the book like their Bible, and so everyone really had the book as their collaborator and respected it and tried to figure out how they could best make a version of this story that exists on the screen — because the book was made to be a book, and they are all working to make a movie that has to feel like it was born to be a movie. That translation is really intriguing to me. And I think they’ve done an incredibly beautiful and accurate job with it.

Jules: Anything new you’re working on now (that you’re allowed to discuss)?

Brian: I’m about to start the tour for Wonderstruck, so that is going to go for a couple of months. And then, of course, Hugo [the Scorcese film] opens at the end of November, and so that is going to take a little while to completely celebrate and enjoy.

And then I’m really ready to start work on my next book. I have an idea. I know what I want to do. I know where it’s going to be set. I have an idea for some of the characters. And, again, I have no idea if it’s going to work. I have no idea how it’s going to come together, but it’s nice having two of these things under my belt. And I’m really looking forward to being able to get back to work.

Because I’m a book-maker, my work is making books. Traveling and talking to people and discussing how I made the books is wonderful, and I feel really, really lucky that I get to do that, and of course there is work involved in doing those sorts of things, but really those are extra bonuses that I get to do as part of my career. But, when it’s time for me to work, work for me means sitting down at a desk with a blank piece of paper and coming up with the next story.

Note: Brian notes in this interview that he’s “about to start” the tour for Wonderstruck, but remember this interview is nearly two months old now. However, the Wonderstruck author tour is still ongoing and is listed here at the book’s spot in cyberspace. Click on “tour” at the top of the site’s pages.

Credit for author photo: Jamey Mazzie.

Illustrations from The Invention of Hugo Cabret are copyright 2007 by Brian Selznick. Used with permission from Scholastic Press.

Illustrations from Wonderstruck are copyright 2011 by Brian Selznick. Used with permission from Scholastic Press.

Our PTO was gracious enough to give us money so we could do a class read of Wonderstruck with the entire third grade. The students come back to the library every third Friday (weird schedule this year) and are loving this beautiful book. We are blogging about it. I can’t wait to share this interview with them. Thank you, Jules.

Lucky you!! And lucky us to have a chance to listen in on your conversation! Thanks for sharing it all…

Jules, I don’t remember you doing a phone interview before. This was really interesting, the back-and-forth of it. Bravo to you, and Bravo to Brian for Wonderstruck. I’ve been talking with the kids at my library about it, and they’ve been excited about and enjoying it.

J. My sister-in-law sent me the Hugo book last year for my birthday. She had read it and knew I would want to too. So yesterday I mailed her Wonderstruck for her Nov 1 birthday. I didn’t read it first, but after reading your interview I’m off to get my own copy! You enrich us all. N.

You never cease to impress me – this is amazing.

Wow! Fantastic interview with an extraordinary creative mind. I love the unravelling of his process. This piece is a gem and I will spread the word widely. I have just discovered your blog, too. Gracias!

[…] Brian Selznick On Wonderstruck, Hugo, and the Joy of […]

[…] comes second and takes him a lot longer. He’s an impeccable researcher. He described working with two Deaf scholars to learn more and told us how devastating the change from silent film to sound film was for the Deaf […]

[…] graduated a decade apart. Jarrett is one of those artists, and the other two are David Wiesner and Brian Selznick. That article is linked here at Jarrett’s site. […]

[…] Brian Selznick (October 27, 2011): “When I made Hugo, I had a very good career before it, but nobody was looking forward to […]

loved all the book

Do you do school/festival visits? Please let me know. Thank you, Liz the Librarian