Seven Questions Over Breakfast with Klaas Verplancke

March 24th, 2014 by jules

March 24th, 2014 by jules

Klaas Verplancke simply doesn’t have breakfast without a single or double espresso. If he has his way, he also has a glass of champagne to kick off his day.

I’m down with both espressos and champagne, so we’ll pretend to have some here, as we chat today.

Now, all my illustrator interviews are pretend. Someone once asked me how I manage to do these interviews when folks live all over the globe; they truly thought I was meeting them for  breakfast in person. I WISH. I’d be game for a children’s-lit version of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Oh, would I!

breakfast in person. I WISH. I’d be game for a children’s-lit version of Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Oh, would I!

But, even if these weren’t cyber-interviews, I’d still have to have a pretend breakfast with Klaas, because he’s in Bologna this week for the Bologna Children’s Book Fair. And if I can’t be there (which I can’t — I’m very much sitting in my home in middle Tennessee), I can at least bring my readers some art from over the pond, as they say — in honor of the fair. Verplancke himself lives and works in Belgium.

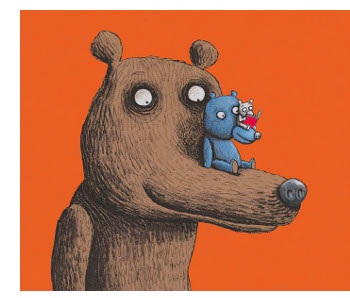

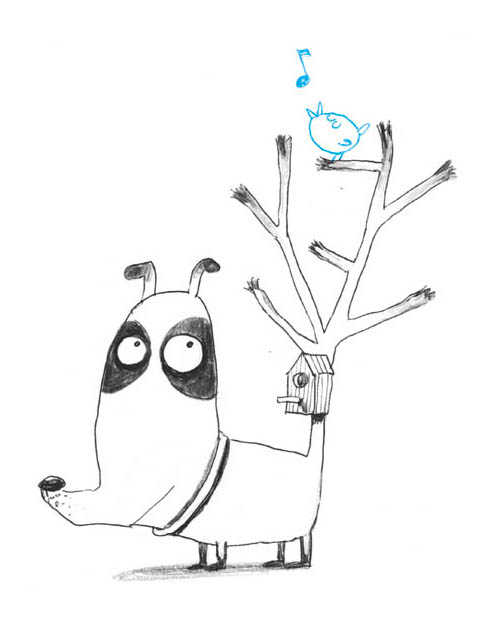

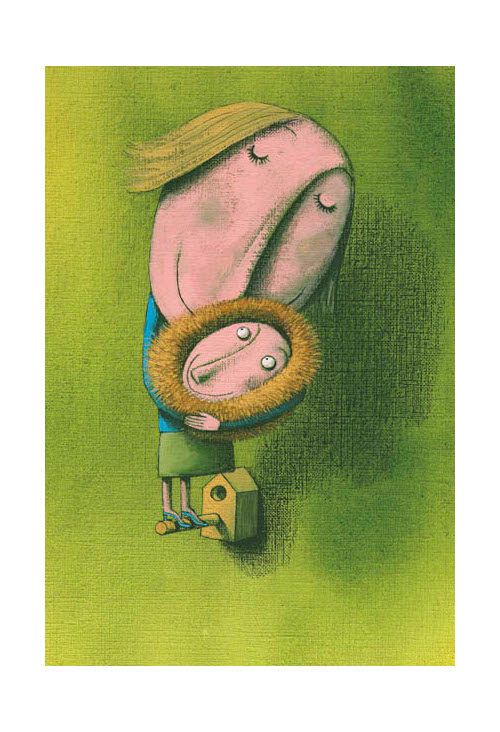

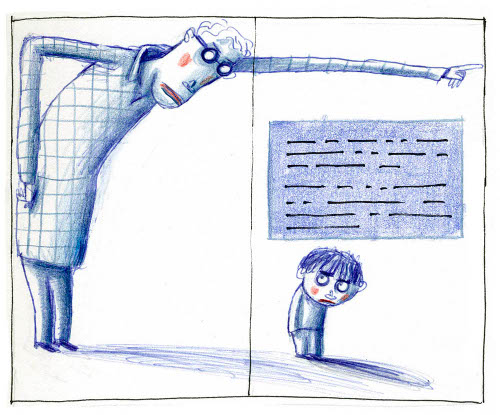

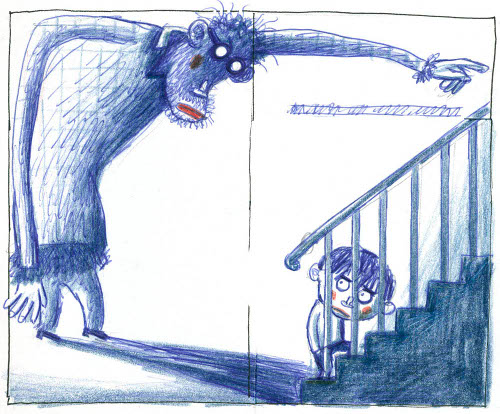

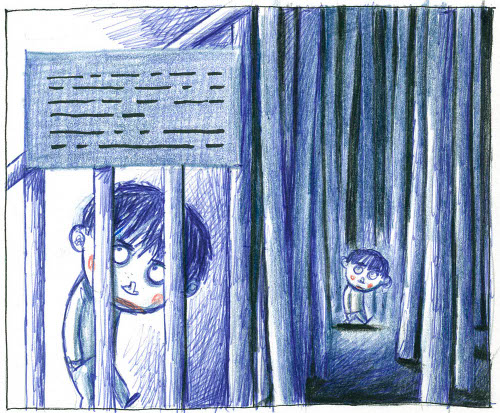

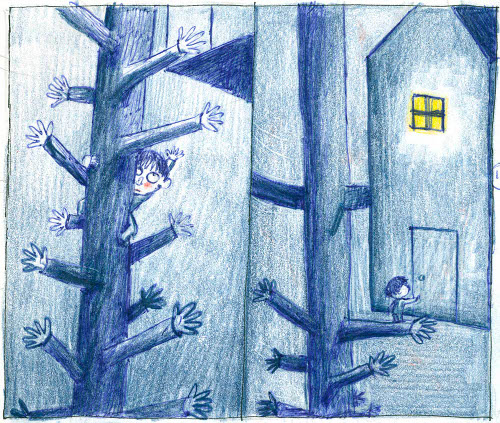

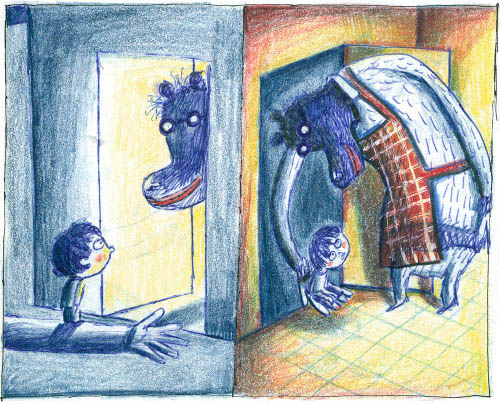

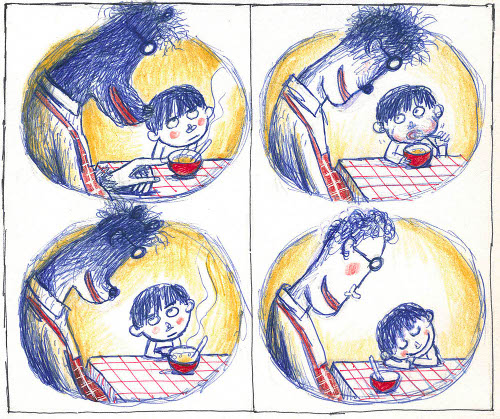

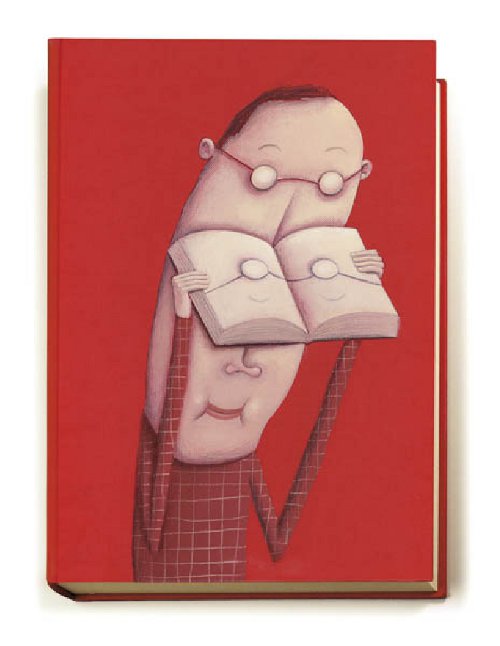

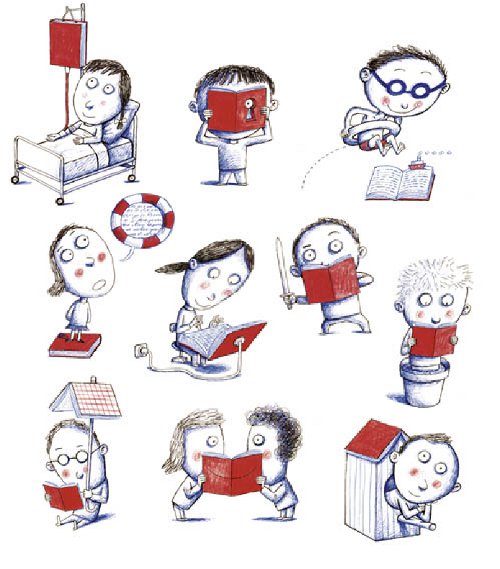

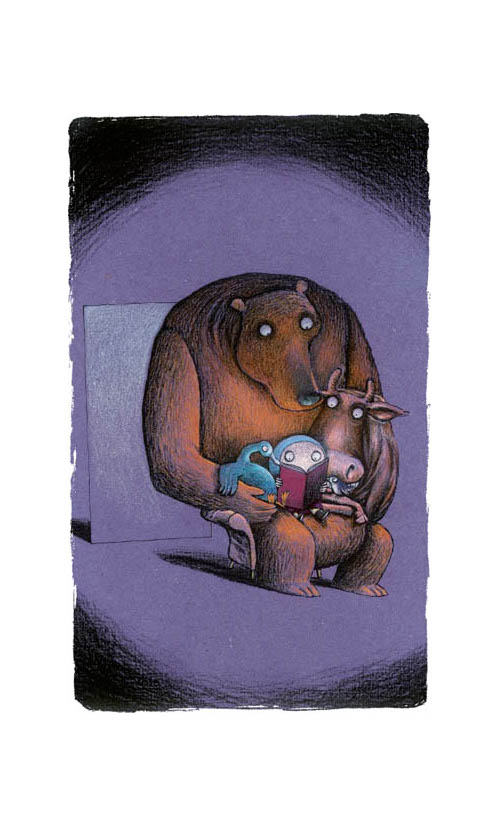

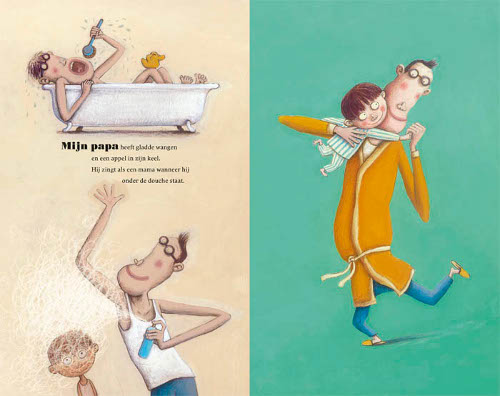

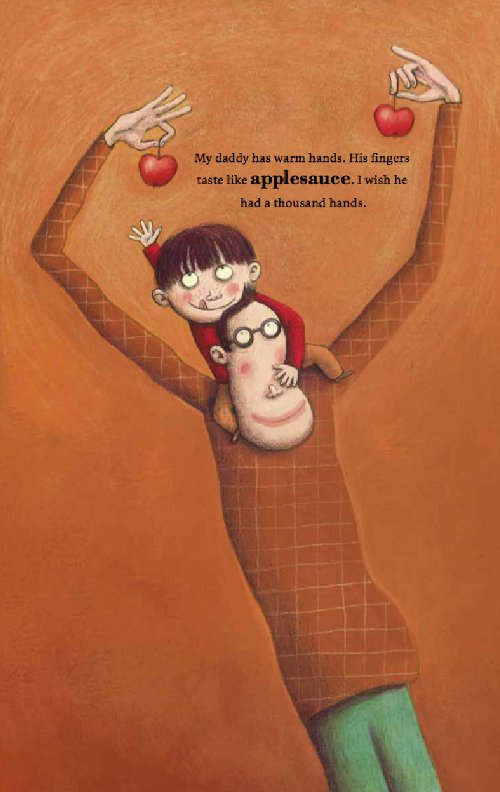

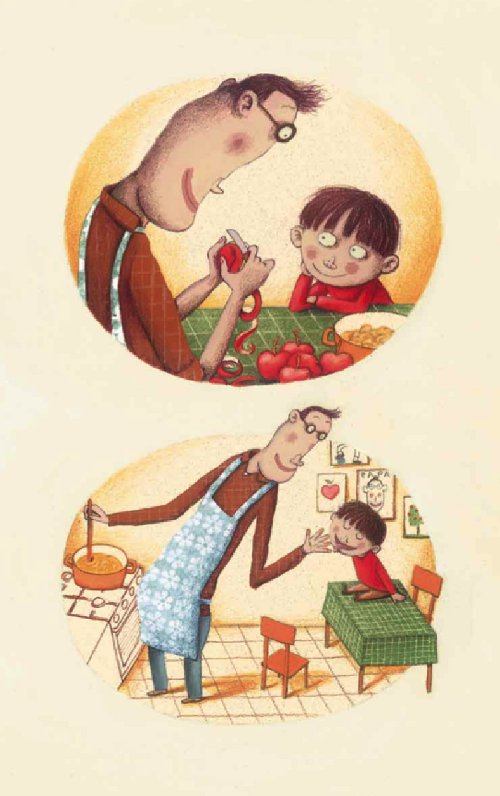

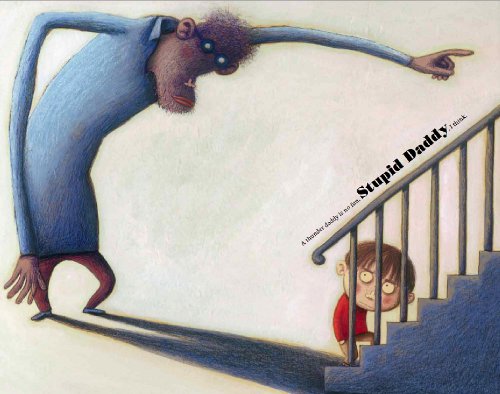

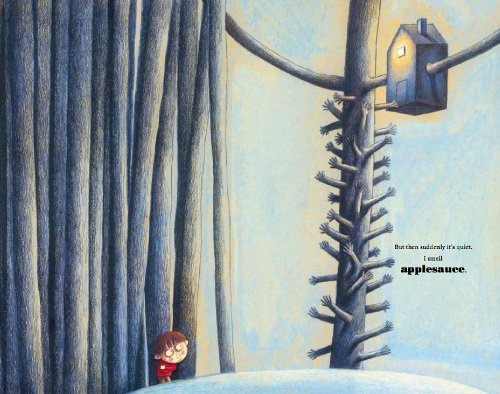

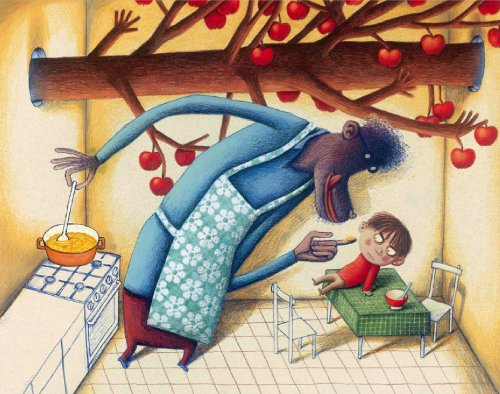

As you’ll read below, Klaas has been illustrating for years, yet only a couple of his children’s books have been brought here to the U.S. In 2012, we got to see Applesauce (which I wrote about here at Kirkus), originally published in Belgium in 2010 and released here by Groundwood. I like that book, but I won’t go on about it here; you can read why at that link. Applesauce was included in the Society of Illustrators’ Original Art exhibit in 2013, and it received a bronze medal at the No. 10 Picture Book Show at 3×3.

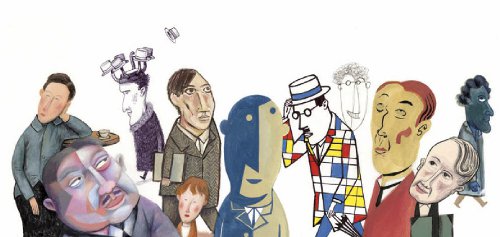

I think Verplancke’s work is best summed up by illustrator Steven Guarnaccia: “[His] work is strange, yet strangely comforting. Beautifully crafted, and beautifully bonkers.” Yep. What Guarnaccia said.

This morning, Klaas shares lots of thoughts on children’s books, lots of passion, and lots of art below, so let’s get to it. I’m curious to know what he’s up to now. I thank him for visiting 7-Imp.

(Note: Klaas may be the first interviewee—I think? There have been many interviews here over the years—to ever direct a question at other illustrators, if anyone wants to chime in. See question #7.)

Jules: Are you an illustrator or author/illustrator?

Klaas: Illustrating author. I puzzle with mostly images, sometimes with words, in function of the story. I start from the idea that everybody is born with the tools for visual reading. We have to cherish and develop this talent. But unfortunately, what usually happens when growing older is the narrowing of our imagination and a growing fear for our spontaneity and intuition to understand what we see and feel.

Jules: Can you list your books-to-date?

Klaas: Almost 150 titles — and more then 60 translations so far. Too long to list here. Only two titles are available in English: The First Klaas Book and Applesauce (Groundwood Books, 2012). Please check my bibliography on my website.

(originally published in Belgium in 2010 and released in the U.S.

by Groundwood Books in 2012)

(Click images to enlarge)

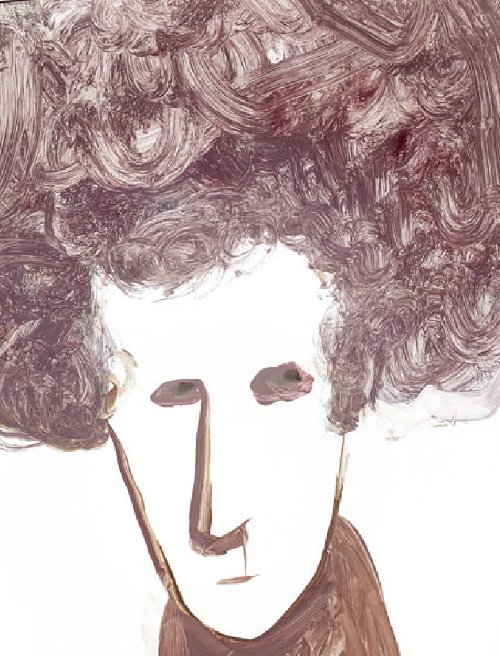

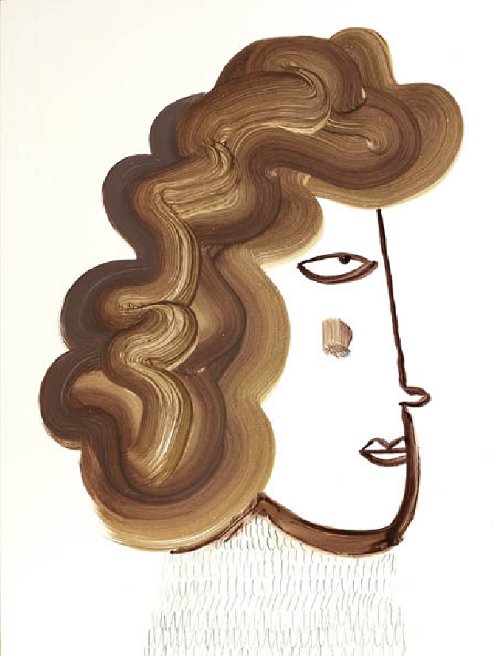

Jules: What is your usual medium?

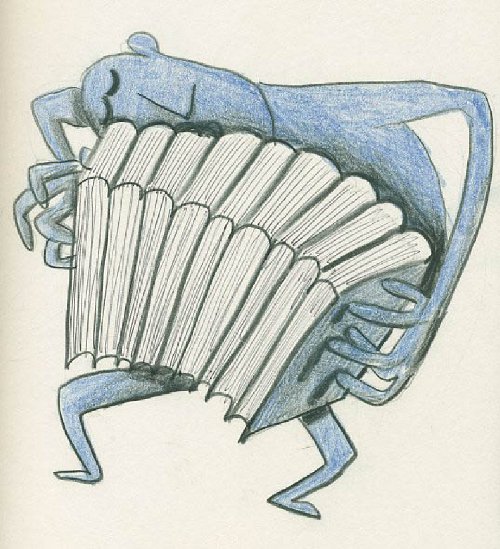

Klaas: My usual medium is my brain. My way of thinking is my style, not a specific technique. Form follows function and usually arises out of experiment.

Recently, I started exploring monotype. But I also like to work with acrylics, gouache, colored pencils, Photoshop and Pentel brushes.

Jules: If you have illustrated for various age ranges (such as, both picture books and early reader books OR, say, picture books and chapter books), can you briefly discuss the differences, if any, in illustrating for one age group to another?

Klaas: A story must find an author and readers, not vice versa. Therefore, the potential reader is never the starting point of my writing — but the angle or the viewpoint of the characters in my story, which will ultimately determine what readers my story will attract. When you tell a story about a house and you describe the value, the dimensions, and the construction, then you will attract other readers, as opposed to describing the color of the tiles or the flowers on the wallpaper.

I always get curled toes in the discussion on the suitability of books for children. One always throws all children on a pile, as if The Child exists. Like a baker would bake his bread for a particular kind of child. Let’s apply this reasoning to adults to show how absurd this argument is: Not all adults understand and read Kafka’s books. So, the books of Kafka are not suitable for adults.

In assessing books, one mistakenly starts from the perception that ‘not understanding’ is a problem. “We think we understand the rules when we become adults, but what we really experience is the narrowing of our imagination,” said David Lynch. Maybe we should assume that ‘not understanding’ creates fascination and imagination, that we should understand that there is something called mystery, and that children intuitively assume that they need to learn if they want to grow. Let me quote Guus Kuijer: “If we don’t want to learn, then everything is elitist and unintelligible, even opening a door.”

Jules: Where are your stompin’ grounds?

Klaas: Brugge, close to the Groeninge Museum. My neighbors are Bosch, Memling, and van Eyck.

Jules: Can you tell me about your road to publication?

Klaas: I produced my first illustrations when I was still in uniform. It is a career born more or less out of need: As I was liable for military service, I helped shape the military weekly, Vox, and when there was a lack of photos, I filled in any empty spaces with drawings. I studied Advertising Graphics and Photography from 1982 to 1986 in an art high school in Ghent, Belgium. After my military service, I worked for a few advertising agencies and continued to do my illustrating after office hours. In 1990, I decided to become a full-time illustrator. Advertising acted as a handy training ground for my new profession, teaching me to analyse issues and to get a story across to the public at large.

Jules: Can you please point readers to your web site and/or blog?

Klaas: http://www.klaas.be.

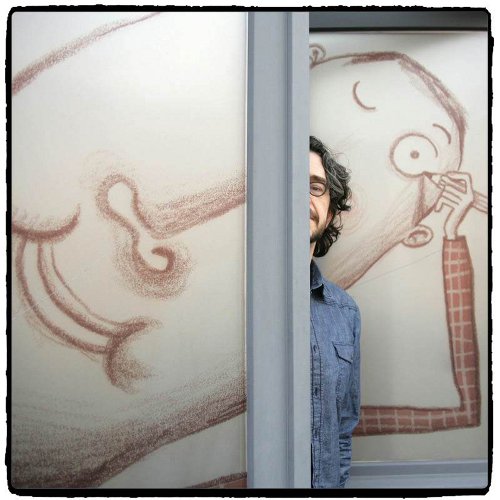

Klaas and Klassen at the opening

Jules: If you do school visits, tell me what they’re like.

Klaas: I lecture for students. I try to make them familiar with visual literacy and storytelling so that they can apply this in their future jobs — and convey an enthusiasm and love for books.

7-Imp: If you teach illustration, by chance, tell me how that influences your work as an illustrator.

Klaas: Every day I do a lot of things intuitively in my artwork. Teaching requires me to bring these actions into words. In other words, teaching is a constant self-reflection, which is so very instructive for me. I give a lot, but I get a lot back from the students themselves. Their questions, thresholds, and viewpoints broaden my way of seeing and evaluating.

Jules: Any new titles/projects you might be working on now that you can tell me about?

Klaas: A new picture book after the success of Applesauce is particularly difficult and confrontational. I have a dozen books going through my head.

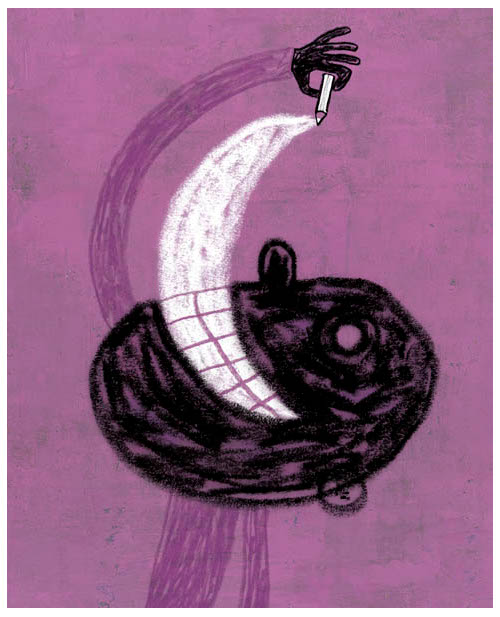

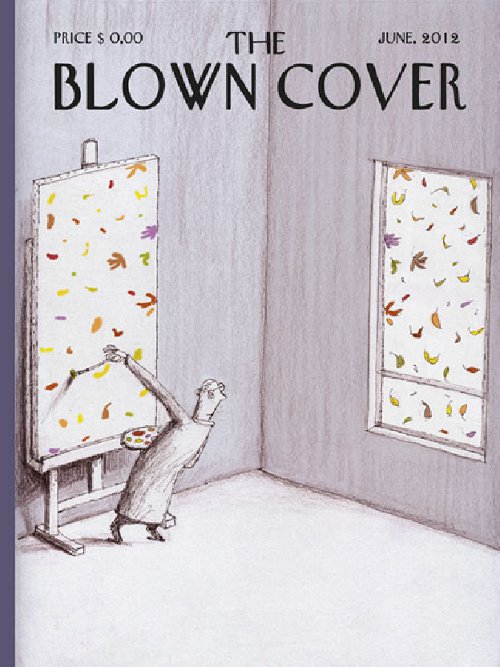

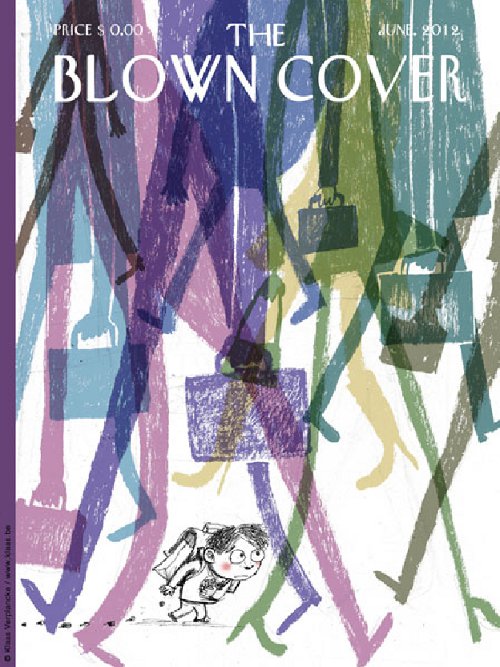

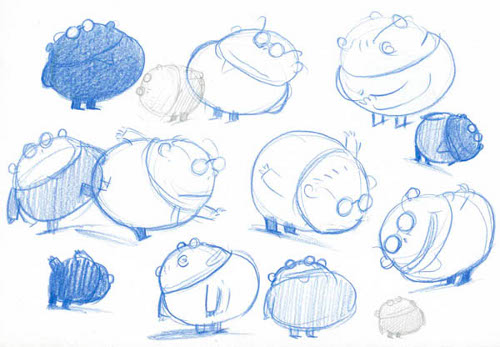

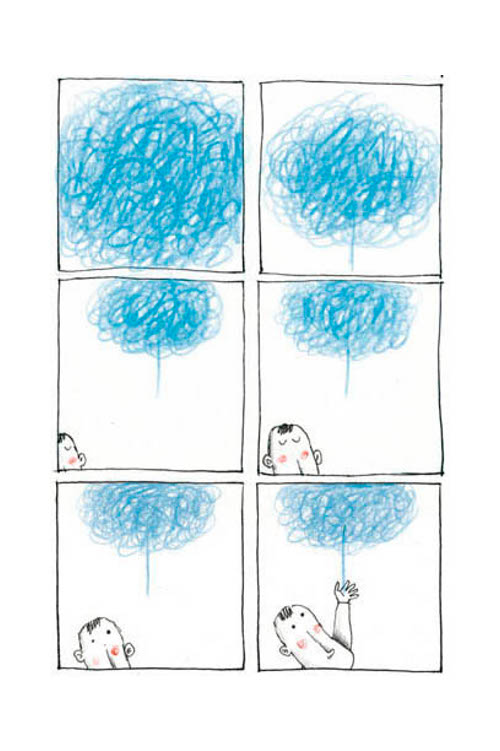

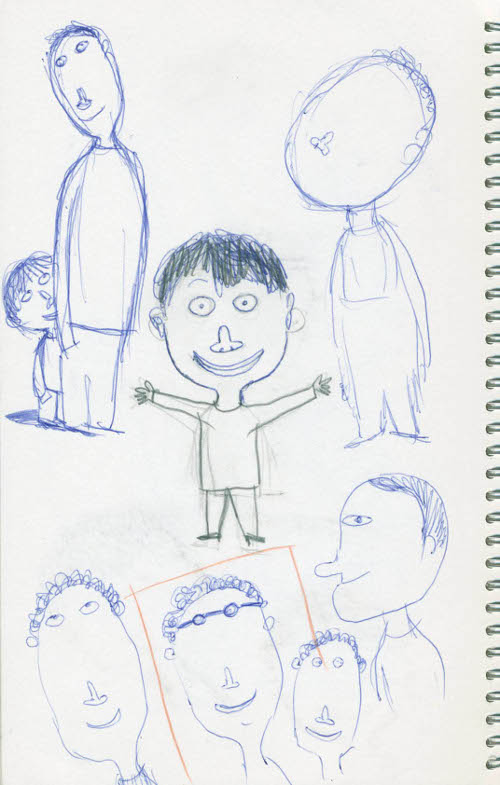

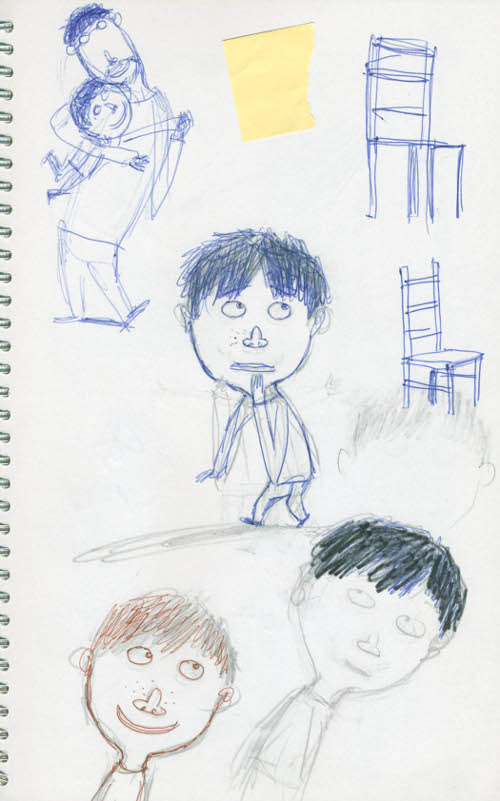

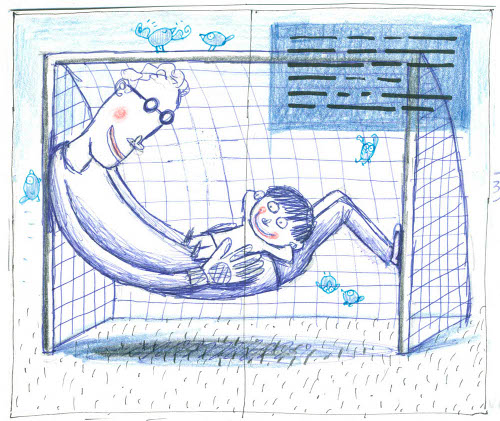

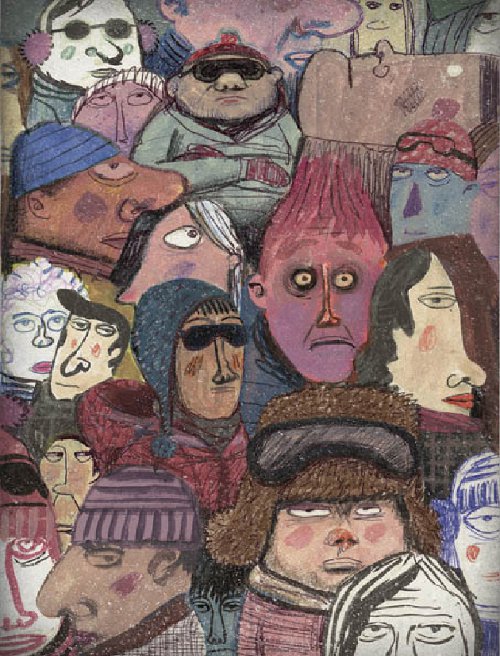

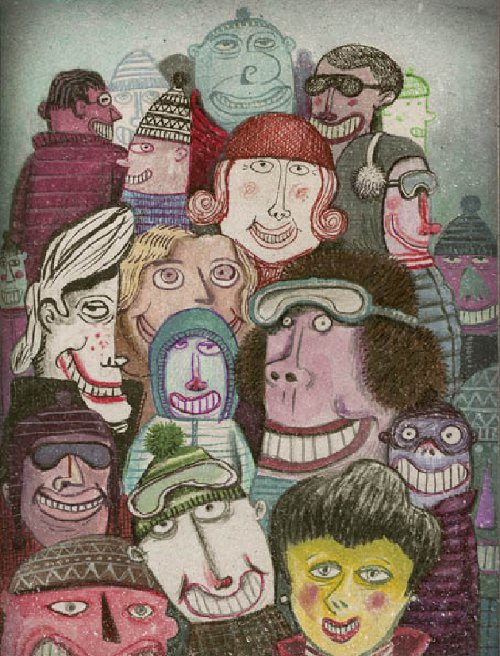

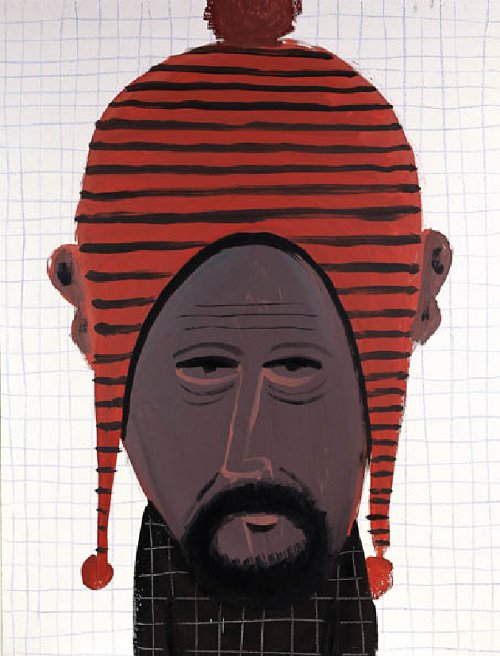

In the meantime, I’m engaged in two new animation projects as an art director, which is very exciting. Here are character designs and storyboard sheets:

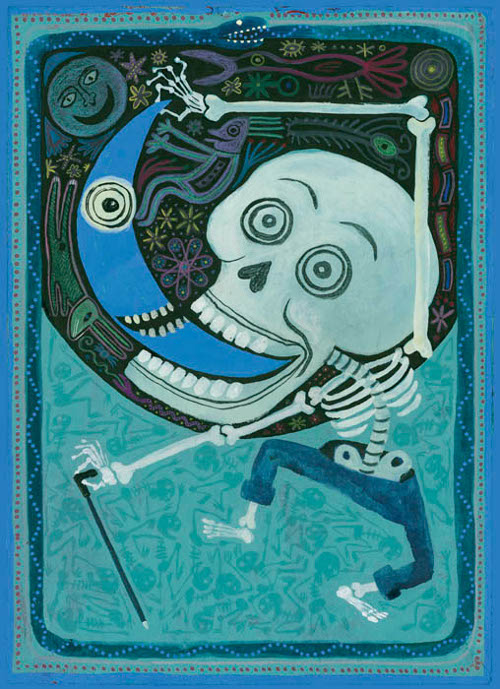

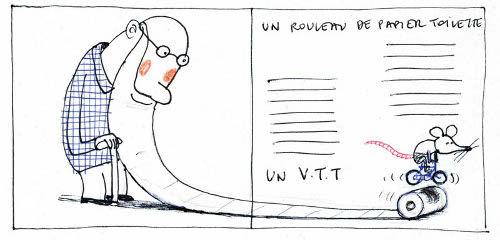

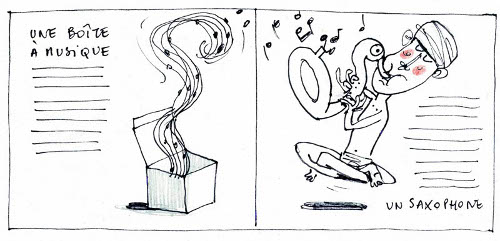

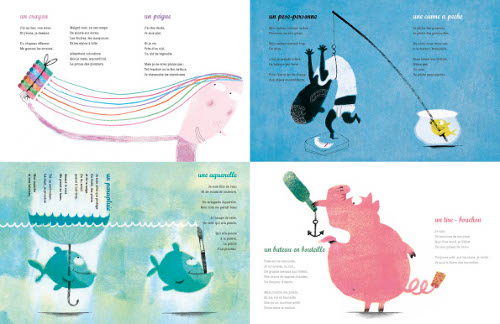

Below is a preview of another new book project, a series of humorous interviews with daily objects. The title in French (the language of the original rhyming text was written by Pierre Coran, inventor and creator of this concept and father of another famous french writer, Carl Norac) is Paroles d’une casserole & d’autres bricoles. Google translates this as Words of a Pan and Other Odds.

Every spread combines two objects/interviews in one surrealistic, weird, or crazy scene. I use a special digital technique, which I cannot yet reveal completely, but it is based on a combination of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black — and inspired by vintage Polish and Russian picture books. The first book of this series will be published by the end of this year.

In addition, I am currently working on two new picture books, for which I wrote the text — but they will be illustrated by two other illustrators. Very exciting! One is a famous illustrator from Japan; the other, an author from Poland, not yet known. But, unfortunately, I cannot reveal the names yet. When writing these stories, I obviously had particular ideas in mind. Now it is extremely exciting and interesting to compare my personal vision with the imagination of another illustrator. It opens my mind, broadens my horizons, and obliges me to question certain evidences or automations.

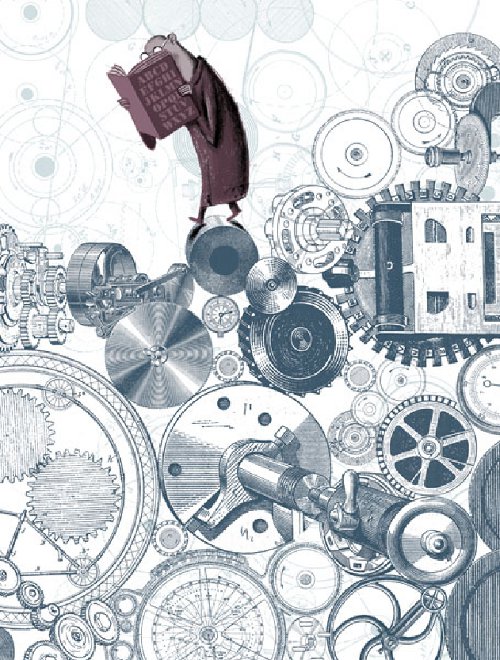

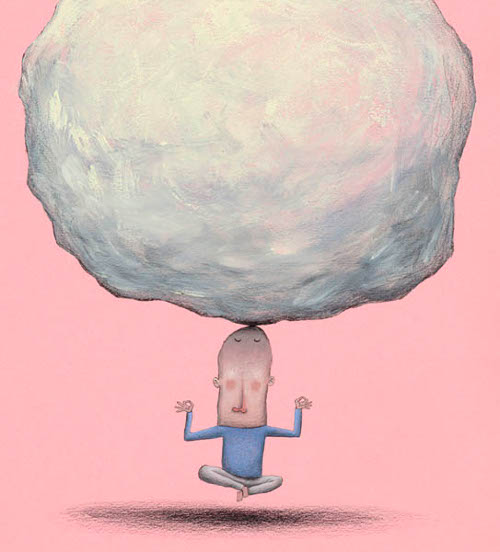

These are sketchy illustrations I made for the Dare to Dream project:

Okay, our espressos (and champagne) are ready, and it’s time to get a bit more detailed with seven questions over breakfast. I thank Klaas again for visiting 7-Imp.

Okay, our espressos (and champagne) are ready, and it’s time to get a bit more detailed with seven questions over breakfast. I thank Klaas again for visiting 7-Imp.

1. Jules: What exactly is your process when you are illustrating a book? You can start wherever you’d like when answering: getting initial ideas, starting to illustrate, or even what it’s like under deadline, etc. Do you outline a great deal of the book before you illustrate or just let your muse lead you on and see where you end up?

whose questions were the inspiration for Applesauce

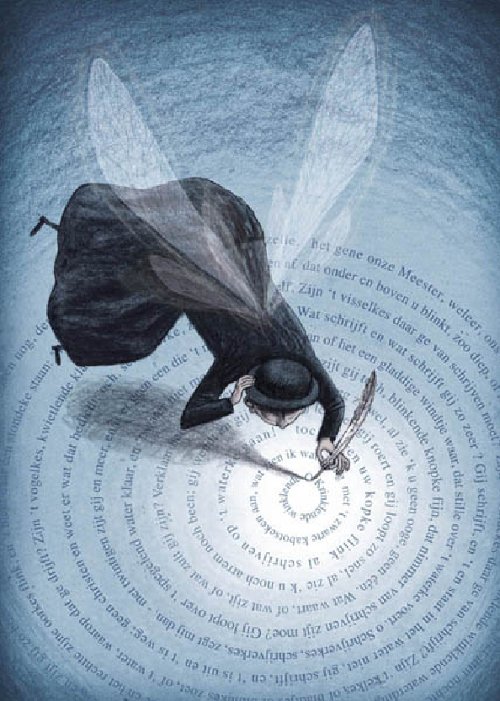

Klaas: Picasso once said, “There are artists who transform the sun into a yellow spot, but some artists transform a yellow spot into a sun.” I would like to suggest a variation on this quote: There are illustrators who transform a word into an image, but some illustrators transform an image into a feeling or a thought.

Drawing is reproducing what you see. But René Magritte was right: “Ceci n’est pas une image.” What you see is not an image but imagination, and we all look and imagine different about the same. That’s why the storyteller in The Little Prince draws a sheep in a box with two holes. What we look at is a shell. What’s really important is invisible.

We look, we understand, and we feel. That’s the process of seeing. He who understands this process understands how to imagine.

(Click to enlarge second image)

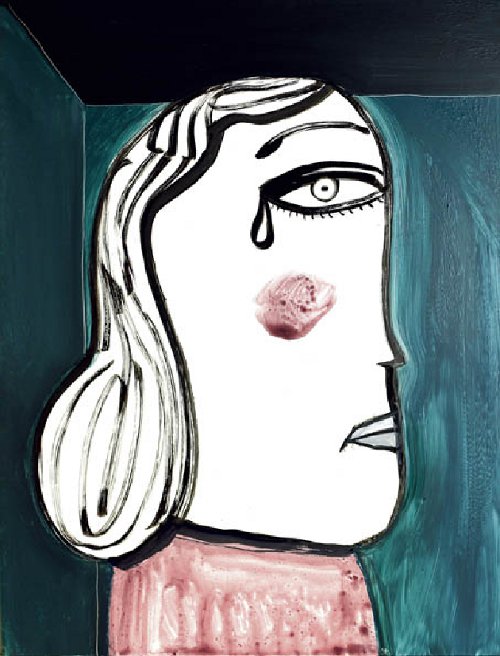

When I illustrate, I try to draw what we see when we close our eyes, to capture the invisible in images. All those feelings we all experience ourselves but we cannot represent in any way: How do you draw joy, loneliness, being in love, hope, sorrow? How do you give a face to such abstract concepts that are both surprising and immediately recognizable?

That is why I fret a great deal before I actually get down to drawing. I have to delve long into a story before I can get something out of it. Images emerge from a chaos of thoughts, impressions, and memories — and gradually take shape. It’s a long, tough, and unknown road between the image in your head and the final result on paper or in a book. It’s an adventure, because you never know which obstacles you may encounter en route. But you always come home differently than when you left, even after 22 years of making books.

The silence of an image is deafening significant. It is the secret place where reader/viewer and story meet. I like this intriguing contradiction in terms, because it’s a sort of perfect definition of the essence of a good illustration (or image, in general), namely the lack of response or the suggestion that stimulates the soundless process of thinking and searching for the meaning, the story behind the layers we see in an image. That respect for mystery, to not fill in everything, is in my opinion one of the essential differences between print and digital media. The reader of a soundless, static image has to create the third, fourth, and fifth dimension within his imagination. What happened before and after the image I see? Whereas in digital media every aspect is determined.

Seeing is believing. Or should we say: Seeing is feeling, and feeling is believing. Really happened is not important as long as it is true. The art of illustrating is that the reader images that the image is his own imagination.

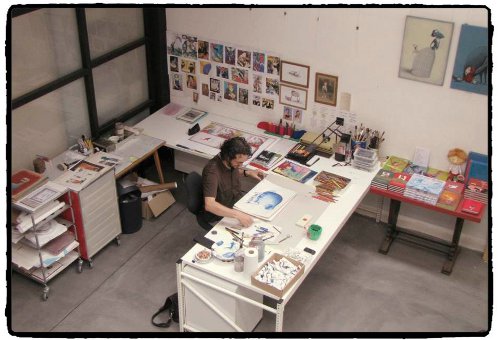

2. Jules: Describe your studio or usual work space.

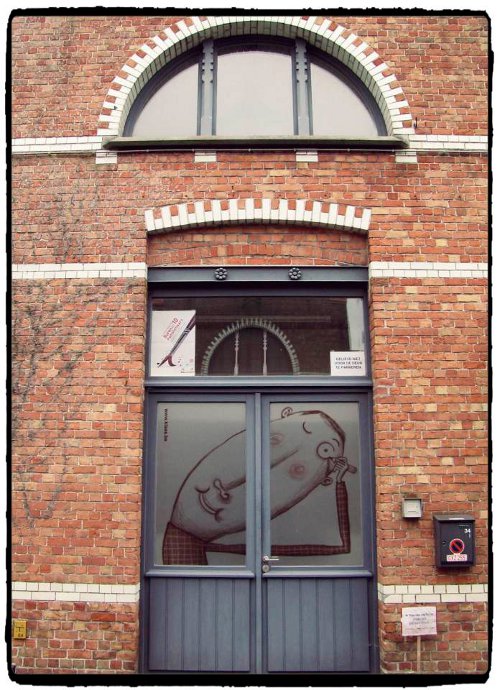

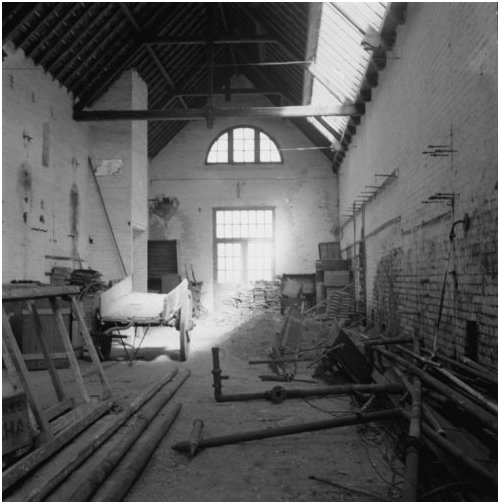

Klaas: I think the pictures speak for themselves. A long time ago, this place was a factory. It looked like this:

Now it looks like this:

3. Jules: As a book-lover, it interests me:  What books or authors and/or illustrators influenced you as an early reader?

What books or authors and/or illustrators influenced you as an early reader?

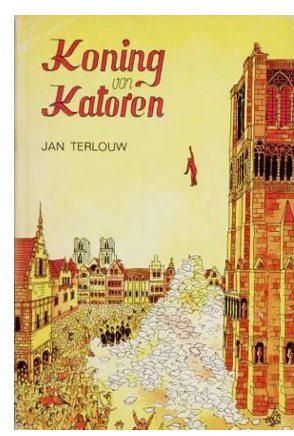

Klaas: Like every true Belgian, I was a big fan of the famous Belgian comics, such as Tintin, the Smurfs, Guust Flater, Suske & Wiske, Lucky Luke, and Jommeke. Apart from that, I was a slow reader of children’s books, but I read all the Flemish and Dutch classics. One of the most intriguing books was, no doubt, Koning van Katoren by Jan Terlouw. I loved this book, because it was an adventurous, exciting, and at once classic and modern fairy tale I did not fully understand. It continued to fascinate me, and the layering of the story and the themes became clear later.

4. Jules: If you could have three (living) authors or illustrators—whom you have not yet met—over for coffee or a glass of rich, red wine, whom would you choose? (Some people cheat and list deceased authors/illustrators. I won’t tell.)

Klaas: God, Jeroen Bosch, and myself at the age of 80.

5. Jules: What is currently in rotation on your iPod or loaded in your CD player? Do you listen to music while you create books?

Klaas: Everything between Monteverdi, Rammstein, and complete silence. It depends on the mood. Right now I’m listening to some ambient mix.

6. Jules: What’s one thing that most people don’t know about you?

Klaas: I can hold my breath for two minutes. I prefer well-baked bread, especially the crunchy tops. And I have an obsessive technique for filling the dishwasher.

7. Jules: Is there something you wish interviewers would ask you — but never do? Feel free to ask and respond here.

Klaas: In fact, this a question I would like to ask to my colleagues: When do you know an image is finished? When and why do you stop?

Honestly, it’s the deadline that decides when I finish a drawing. I use all the time I have, and still it is always different from what I imagined. Every nuance, every space, every line is a choice and means the release of other ideas and opportunities. You draw a lot to draw little. It’s a strange cocktail of excitement and frustration. Finishing a detail and then back stepping. These three, four seconds without doubts — these are the happiest moments in my work.

But I can live with the imperfection. That makes art human. A ten-year-old girl once said: “Children need to see art from time to time, so that we never forget that some things in this world are made with love and passion.”

while I was posing as a stand-in for a portrait shoot for someone else.”

Jules: What is your favorite word?

Klaas: “Yes.”

Jules: What is your least favorite word?

Klaas: “No.”

Jules: What turns you on creatively, spiritually or emotionally?

Klaas: Everything that looks or sounds seemingly common or simple, but hides conviction, sacrifice, vulnerability, sustained hard labor, and profound thinking — such as, Ella Fitzgerald singing, or Hopper’s painted light, or the reflection in van Eyck’s jewelry.

Jules: What turns you off?

Klaas: Pretension and immodesty. Heroes do not exist. You’re nobody, when nobody is watching.

7-Imp: What is your favorite curse word? (optional)

Klaas: “Miljaardenondedjubegot.” Don’t try this at home. It’s Dutch.

Jules: What sound or noise do you love?

Klaas: Crunchy bread.

Jules: What sound or noise do you hate?

Klaas: Chalk scratching on a chalkboard.

Jules: What profession other than your own would you like to attempt?

Klaas: Being Bach, Picasso, Magritte, and Santa Claus at the same time.

Jules: What profession would you not like to do?

Klaas: Painting dots on dice.

Jules: If Heaven exists, what would you like to hear God say when you arrive at the Pearly Gates?

Klaas: “Well done lad. But next time you should be drawing instead of losing time on Facebook.”

All artwork and images are used with permission of Klaas Verplancke.

APPLESAUCE. English translation copyright © 2012 by Helen Mixter. Published in 2012 by Groundwood Books, Toronto. The APPLESACUE art and sketches are re-posted here from this 2012 post.

The spiffy and slightly sinister gentleman introducing the Pivot Questionnaire is Alfred, © 2009 Matt Phelan.

Had to comment because this post just BLEW MY MIND!!!! (In a very good way.) 🙂 e

You’d need the courage accumulated in 80 yrs to hang with God and Bosch! One of your best interviews, Jules! Oh, and to answer Verplancke’s question, I don’t know, but I stop when it smells good – just as I do when baking bread.

My mind is blown too!! I LOVE Klaas Verplancke ! I love this interview and I am super inspired. Thank you for this wonderful post!!

Juicy, fun, hilarious, love it! What a cool, thoughtful person. Thanks for sharing him and so much art. I just don’t get the orange pants selfie! Although my Little, who LOVES orange will think it is fantastic. So glad he’s doing art and sharing art with the world and agreed to share with you and therefore us.

I think this is my favorite 7-Imp interview ever. Gotta love an author-illustrator who quotes David Lynch. 🙂

Wow, this is a GOOD one. I’m all kinds of art envy after looking at this. And also all kinds of studio envy.

I think I need t reread that a whole bunch of times. (Too bad I’m supposed to be writing…!) Lots to think about. Love his work and musings. Thanks for this!

both Klaas and this profile/post are FANTASTIC! thank you.

Exhilarating, clever, and true….Klaas is awesome! Miljaardenondedjubegot!!

Infinite thanks for these compliments! it’s an honor and a huge pleasure to be invited for a breakfast with Jules and all of you.

Wow. This knocked my socks off!

Inspiration explosion! love love love it, especially the shot of his orange outfit.

Wow wow wow!! What a fantastic post! I am planning to feature Klaas on my blog soon, but wow do I have a lot to measure up to! Love the photographs of his studio especially!!!

[…] Picasso powiedział kiedyś: “Istnieją artyści, którzy zmieniają słońce w żółtą plamę, ale są też tacy, którzy zmieniają żółtą plamę w słońce”. Chciałbym zaproponować wariację na temat tego cytatu: Istnieją ilustratorzy, którzy zmieniają słowo w obraz, ale są też tacy, którzy zmieniają obraz w uczucie lub myśl. Rysowanie to odtwarzanie tego, co widzimy. Ale René Magritte miał rację: “To nie jest obraz”. To, co widzimy, to nie obraz, a wyobrażenie, wszyscy inaczej patrzymy na te same rzeczy i inaczej je sobie wyobrażamy. To dlatego narrator w “Małym Księciu” rysuje owieczkę w pudełku z dziurami. To, na co patrzymy, to tylko skorupa. To, co naprawdę ważne, jest niewidzialne. Patrzymy, rozumiemy i czujemy. Na tym polega proces widzenia. Ten, kto rozumie ten proces, wie, jak używać wyobraźni. Gdy ilustruję, staram się rysować to, co widzimy, gdy zamkniemy oczy, uchwycić w obrazach to, co niewidzialne. Wszystkie te uczucia, których doświadczamy, ale nie możemy ich w żaden sposób przedstawić. Jak narysować radość, samotność, zakochanie, nadzieję, żal? Jakie oblicze nadać tak abstrakcyjnym pojęciom, które są zarazem zaskakujące i natychmiastowo rozpoznawalne? Dlatego zawsze długo zmagam się ze sobą, zanim faktycznie wezmę się do rysowania. Muszę długo zagłębiać się w opowieść, zanim będę w stanie coś z niej wydobyć. Obrazy wyłaniają się z chaotycznej masy myśli, wrażeń i wspomnień – i stopniowo nabierają kształtu. Droga od obrazu w głowie do końcowego efektu na papierze lub w książce jest długa, trudna i niezbadana. Jest to rodzaj przygody, bo nigdy nie wiadomo, jakie przeszkody się napotka. Ale zawsze wraca się z tej drogi do domu już jakoś zmienionym, nawet jeśli tworzy się książki już od 22 lat. Milczenie obrazu jest ogłuszająco znaczące. To właśnie to tajemne miejsce, w którym czytelnik/patrzący i opowieść spotykają się ze sobą. Lubię ten intrygujący oksymoron, ponieważ jest on czymś w rodzaju doskonałej definicji istoty dobrej ilustracji (albo w ogóle obrazu). Mam na myśli ten brak odpowiedzi czy sugestię, która stymuluje bezgłośny proces myślenia i poszukiwania znaczeń, historii ukrytej za widocznymi warstwami obrazu. Ten szacunek dla tajemnicy, który każe nie dopowiadać wszystkiego, jest moim zdaniem jedną z kluczowych różnic pomiędzy drukiem a mediami elektronicznymi. Odbiorca bezgłośnego, statycznego obrazu musi stworzyć trzeci, czwarty i piąty wymiar we własnej wyobraźni. Co wydarzyło się przed obrazem, który widzę, i co wydarzy się po nim? W mediach elektronicznych wszystkie wymiary są już z góry określone. Patrzeć znaczy wierzyć. Albo raczej: Patrzeć znaczy czuć, a czuć znaczy wierzyć. Dopóki to jest prawdą, nie jest ważne, co wydarzyło się naprawdę. W sztuka ilustrowania chodzi o to, by odbiorca wyobraził sobie, że obraz ma swoją własną wyobraźnię. Źródła: blog blaine.org […]

[…] Picasso powiedział kiedyś: “Istnieją artyści, którzy zmieniają słońce w żółtą plamę, ale są też tacy, którzy zmieniają żółtą plamę w słońce”. Chciałbym zaproponować wariację na temat tego cytatu: Istnieją ilustratorzy, którzy zmieniają słowo w obraz, ale są też tacy, którzy zmieniają obraz w uczucie lub myśl. Rysowanie to odtwarzanie tego, co widzimy. Ale René Magritte miał rację: “To nie jest obraz”. To, co widzimy, to nie obraz, a wyobrażenie, wszyscy inaczej patrzymy na te same rzeczy i inaczej je sobie wyobrażamy. To dlatego narrator w “Małym Księciu” rysuje owieczkę w pudełku z dziurami. To, na co patrzymy, to tylko skorupa. To, co naprawdę ważne, jest niewidzialne. Patrzymy, rozumiemy i czujemy. Na tym polega proces widzenia. Ten, kto rozumie ten proces, wie, jak używać wyobraźni. Gdy ilustruję, staram się rysować to, co widzimy, gdy zamkniemy oczy, uchwycić w obrazach to, co niewidzialne. Wszystkie te uczucia, których doświadczamy, ale nie możemy ich w żaden sposób przedstawić. Jak narysować radość, samotność, zakochanie, nadzieję, żal? Jakie oblicze nadać tak abstrakcyjnym pojęciom, które są zarazem zaskakujące i natychmiastowo rozpoznawalne? Dlatego zawsze długo zmagam się ze sobą, zanim faktycznie wezmę się do rysowania. Muszę długo zagłębiać się w opowieść, zanim będę w stanie coś z niej wydobyć. Obrazy wyłaniają się z chaotycznej masy myśli, wrażeń i wspomnień – i stopniowo nabierają kształtu. Droga od obrazu w głowie do końcowego efektu na papierze lub w książce jest długa, trudna i niezbadana. Jest to rodzaj przygody, bo nigdy nie wiadomo, jakie przeszkody się napotka. Ale zawsze wraca się z tej drogi do domu już jakoś zmienionym, nawet jeśli tworzy się książki już od 22 lat. Milczenie obrazu jest ogłuszająco znaczące. To właśnie to tajemne miejsce, w którym czytelnik/patrzący i opowieść spotykają się ze sobą. Lubię ten intrygujący oksymoron, ponieważ jest on czymś w rodzaju doskonałej definicji istoty dobrej ilustracji (albo w ogóle obrazu). Mam na myśli ten brak odpowiedzi czy sugestię, która stymuluje bezgłośny proces myślenia i poszukiwania znaczeń, historii ukrytej za widocznymi warstwami obrazu. Ten szacunek dla tajemnicy, który każe nie dopowiadać wszystkiego, jest moim zdaniem jedną z kluczowych różnic pomiędzy drukiem a mediami elektronicznymi. Odbiorca bezgłośnego, statycznego obrazu musi stworzyć trzeci, czwarty i piąty wymiar we własnej wyobraźni. Co wydarzyło się przed obrazem, który widzę, i co wydarzy się po nim? W mediach elektronicznych wszystkie wymiary są już z góry określone. Patrzeć znaczy wierzyć. Albo raczej: Patrzeć znaczy czuć, a czuć znaczy wierzyć. Dopóki to jest prawdą, nie jest ważne, co wydarzyło się naprawdę. W sztuka ilustrowania chodzi o to, by odbiorca wyobraził sobie, że obraz ma swoją własną wyobraźnię. Źródła: blog blaine.org […]