Keeping the City Going: An Interview with Brian Floca

June 15th, 2021 by jules

June 15th, 2021 by jules

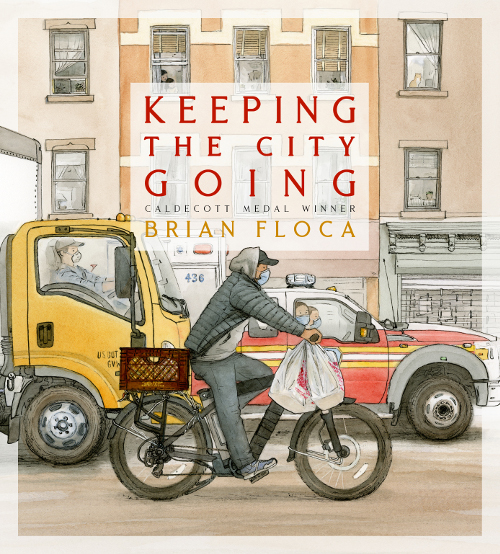

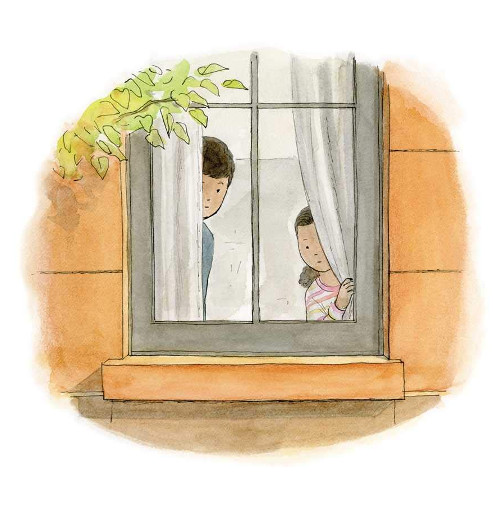

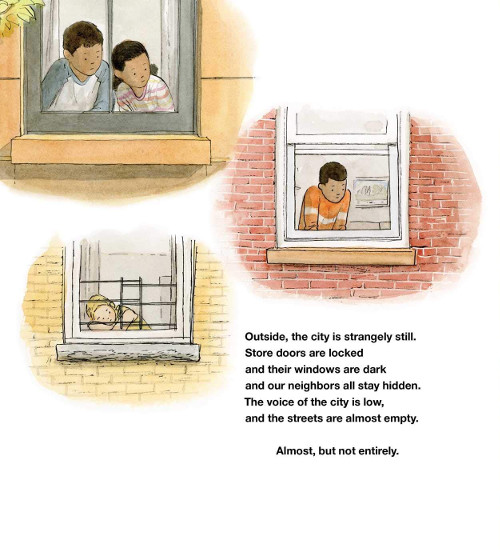

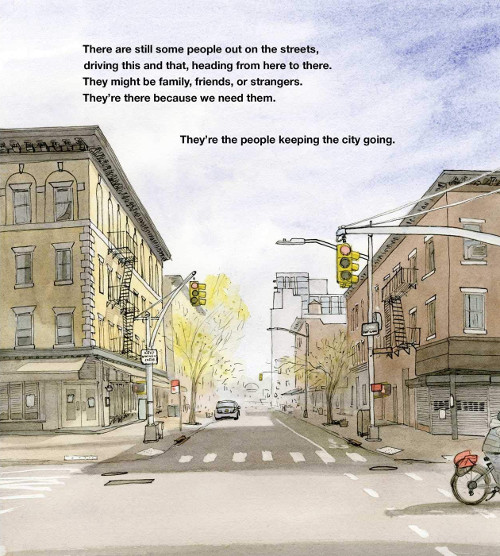

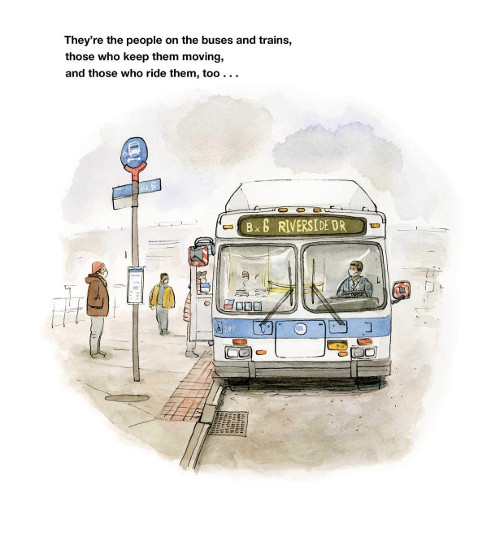

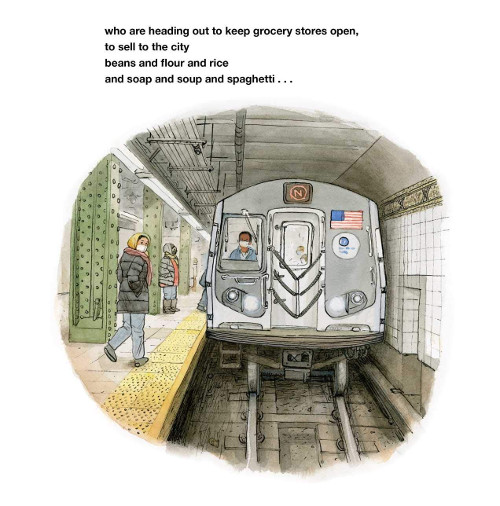

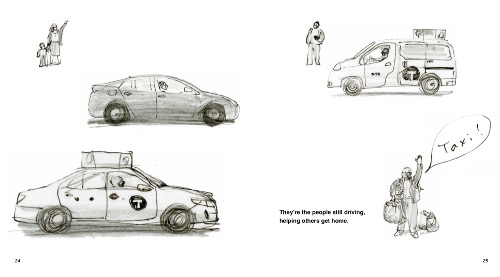

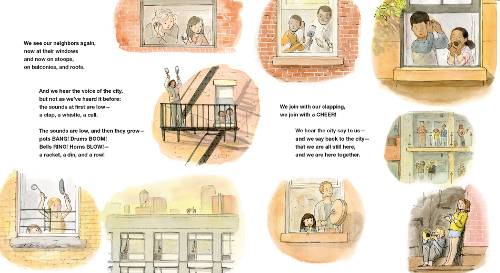

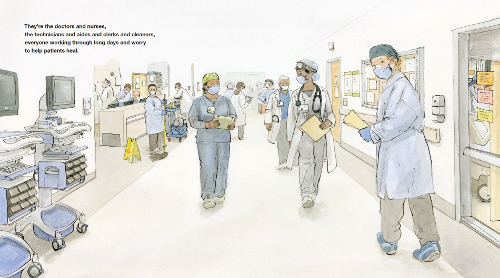

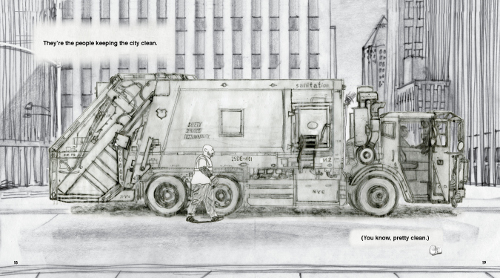

It’s a pleasure to talk to author-illustrator Brian Floca today about Keeping the City Going (Caitlyn Dlouhy/Atheneum, April 2021), what the Horn Book review called a “love letter” to New York City — and to the essential workers that kept cities going during the COVID-19 pandemic. Detailed paintings — in vignettes and expansive, full-bleed spreads — capture New York City last year, a time when it was “strangely still. Yet “[t]here are still some people out on the streets, driving this and that, heading from here to there. They might be family, friends, or strangers. They’re there because we need them. They’re the people keeping the city going.”

For Brian, as he discussses below, the project could be described in many ways. The end result, I think, is thoughtful and reverent, all his gratitude tenderly conveyed. In turn, the book can be a proxy for readers’ gratitude, and it serves as an exquisite time capsule of a sort for last year. I thank him for discussing it with me and, especially, for sharing all the art here. Let’s get right to it.

Jules: You mention in the closing author’s note that it feels both meaningful and “fraught” to make a book about this difficult time. Can you talk about the ways in which it was fraught?

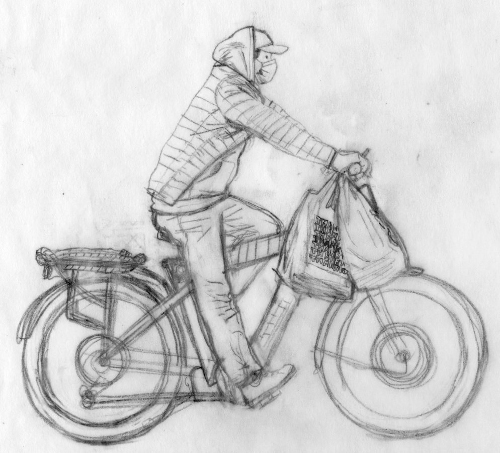

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Brian: First, to state the obvious, there was simply the seriousness of the subject; no matter how gently or indirectly one is trying to engage with the COVID-19 pandemic, one is still dealing with something that has been a source for so many of fear, isolation, stress, and grief. Then there was the awareness that, although we have all been through an ordeal this past year, we have not all been through exactly the same ordeal: Some of us have been able to make the best of it, and some of us have had to endure the worst of it, and the reasons for those disparities are often troubling and sensitive in their own rights. Finally, there was the fact that the nature of the pandemic was evolving, often unpredictably, as the book was being made, and could be expected to continue to evolve even after the book was finished; thus, my notion of what book I ought to be making felt at times like something of a moving target. So, there was a great deal in, and connected with, the subject that wanted to be treated with a high level of care and respect; a great deal in motion; and a tight schedule — and all of that would come and and sit with me at the drafting table quite often.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

That said, it was the things that made the book feel challenging that also made it feel worth trying, and there’s the “meaningful” at the intersection of meaningful and fraught. And I did grant myself some breathing room, I suppose, by never imagining I was trying to tell the story of the whole pandemic, as if any book could. I hoped only that I might be able to do something useful for readers with what I was seeing and experiencing around me. I hope readers will feel I did right by the material I did try to address, and I’ve been glad to see other authors and artists addressing other aspects of our pandemic year, too. We have already seen beautiful and moving books like LeUyen Pham’s Outside, Inside and Stephen Savage’s And Then Came Hope, among others, and there will be more to come. We will want many voices and perspectives on this topic.

and wondering what will happen next. Outside, we see the city we know,

but not as we’ve seen it before.”

(Click illustration to enlarge and see spread in its entirety)

Jules: You mention in this Publishers Weekly piece from December 2020 that this is your “most personal” project thus far in your career. How did it feel? Was that uncomfortable? Do you suddenly want to step way back and do something less personal in scope? Or does it feel validating to see this out in the world now?

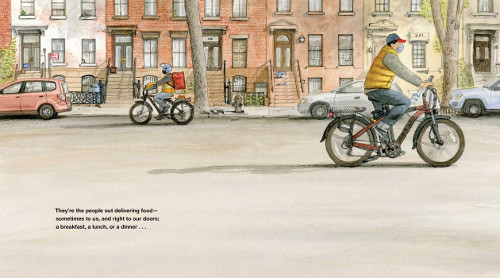

right to our doors; a breakfast, a lunch, or a dinner …

(Click spread to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Brian: Making the book was a way for me to frame and process what I was seeing around me last year — the uncomfortable, yes, but the hopeful, too. The work gave me a sense of purpose and agency, however illusory that agency might have been, and for that alone I’m grateful. And now? I’m glad to be done, thank you, and happy to see the book out and in the world. And seeing it in the world is made happier for me, too, by the hope that here in the United States at least we might finally be moving beyond this crisis, into spring, into summer, into seeing people and going places again. The more the book reads like a memory piece, as opposed to current events, the better!

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

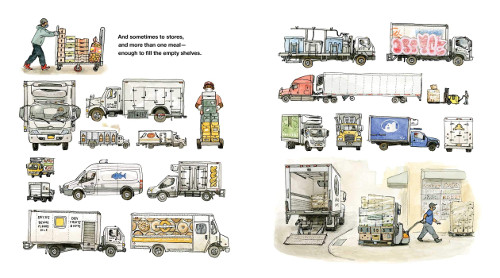

enough to fill the empty shelves.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

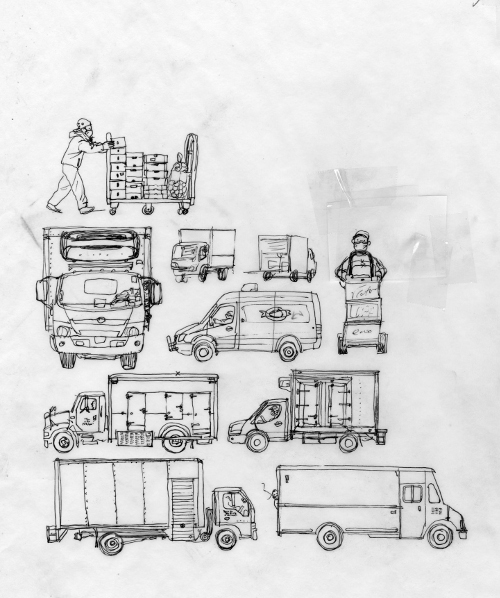

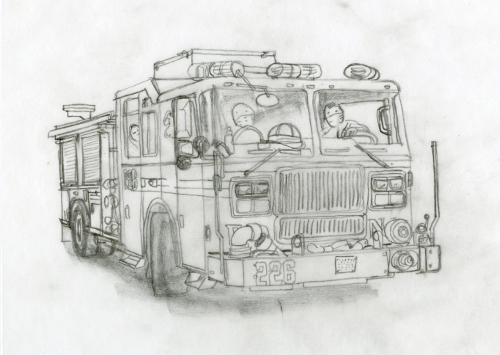

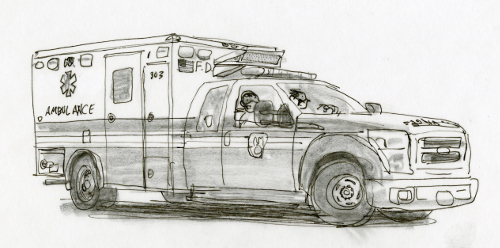

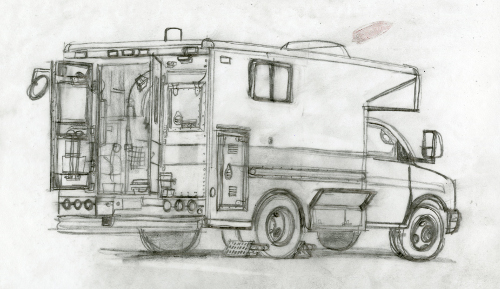

Jules: You also mention there and in the book’s author’s note that drawing vehicles became a coping mechanism. What else got you through the social isolation of last year?

Brian: What really saved me last year were the friends with whom I share studio space in Brooklyn — Sophie Blackall, Doug Salati, and Rowboat Watkins. (We see Sophie when we’re lucky, that is. We’re obliged to share her with the green and rolling fields of upstate New York, where she is establishing Milkwood Farm, a retreat for authors and artists, and where, for some reason, she seems to like to spend time.) After the initial lockdown in New York in March of last year, we took stock of our desk spacing and square footage and felt we could, with precautions, keep the studio running: We all traveled to and from in the open air, on foot or by bicycle; we kept doors ajar and windows open; we stayed out of each other’s faces; and we limited our non-studio activities and interactions. We were, in the new parlance, a pod, and I don’t know what I would have done without it. (It? Them? I’m still figuring out the nuances of the new lingo.)

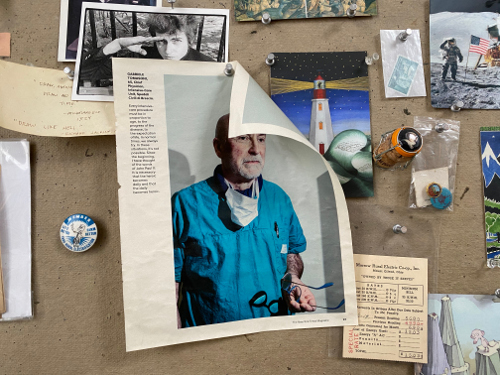

Second, FaceTime and Zoom, for all their limits, have helped so much in maintaining a sense of connection with people I cannot see or visit — in particular, my parents. I think they won’t mind if I say they are not bleeding-edge technophiles, but they have gotten on board with video calls.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: One of the book’s reviews (Kirkus) notes that a “community spirit shines in the use of we.” Did you know immediately that you wanted to take that first-person plural approach? Or did you experiment with other choices?

Brian: I was happy to read that and, no, I can’t remember trying anything else. As discussed earlier, although we have all felt the impact of this year in different ways, we have indeed all felt it. (It turns out I can’t even answer this question without using the word “we.”)

Jules: Did you also know right away that you wanted to close with the making-noise moment, in which everyone is on their stoops and cheering essential workers? (I find that very moving, as someone who doesn’t live in a big city and didn’t get to experience that. You capture it well.)

the sounds at first are low …”

(Click to enlarge spread and read text in its entirety)

Brian: First, let me say this: I have never met a pep rally I didn’t want to skip, and I grew up in Texas, and there were a lot of pep rallies. And I know, too, that the mere act of clapping in a window is not sufficient thanks for what healthcare and other essential workers did for us this past year. And yet, yes, that moment was always going to be in the book. There were evenings last spring when the day was closing, the sun was setting, cases were spiking, stores were closed, streets were empty, none of us knew where this thing was going or how long would it last, and then — just when the light hit a certain angle — the sound of chimes and horns and drums and applause and cheers would come drifting through the air from over and around the block, softly at first and then gaining strength, and I found it very moving to hear it and to join in, too. It was a means of expressing gratitude to the people getting us through this thing; a means of acknowledging to each other our debt to those workers; and, finally, it was a communal activity, a counterpoint to the heavy sense of isolation that so many of us were feeling — an affirmation that this was, as discussed, a “we” event.

Jules: I like how so many essential workers in this book turn and look at the reader. Or is it that they’re turning to look at you, as the author-illustrator chronicling things? How did you think of that? Why that choice?

(Click to enlarge)

Brian: Down with the fourth wall! It’s a favorite little crutch of mine, I suppose — an attempt to create opportunities for a reader to feel engaged with the book.

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: Nerdy design question: Who decided on these beautiful solid- and rust-colored endpapers? And did you get to weigh in on design?

Brian: I’m glad you asked! I’m fortunate to have worked on this book not only with editor Caitlyn Dlouhy but also art director Michael McCartney. Michael and I first worked together on my book Lightship; then The Hinky-Pink by Megan McDonald; then my books Moonshot and Locomotive; and then Old Wolf by Avi — and Michael’s work has been essential to whatever works well in each those titles. I’m especially grateful for his design treatment for the cover of Keeping the City Going, which I think elevates the whole book.

But back to the endpapers: When we settled on the idea of solid color endpapers, Michael suggested we use one of the two colors he had chosen for the type on the cover. And that’s what we did.

(Click to enlarge)

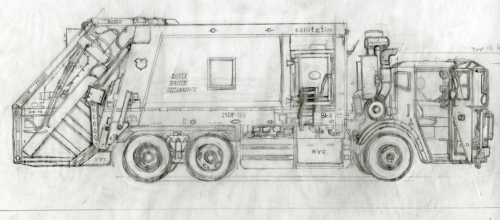

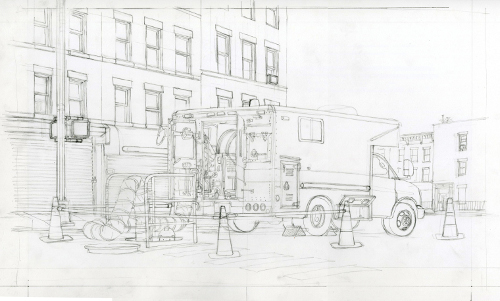

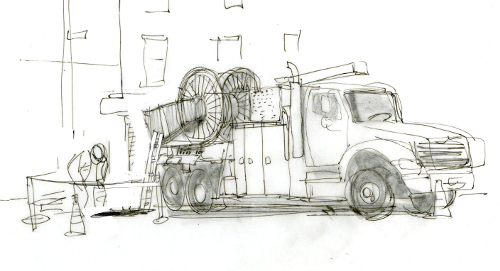

A note about the images above (the sanitation truck): One of the benefits of having a studio in a semi-industrial neighborhood is that you’re near places like NYC Department of Sanitation depots. You don’t appreciate a thing like that until you’re trying to draw all the greebles on a garbage truck and need to double-check a bumper or a knob! Step out the door, walk two blocks, and you’ve got everything you need!

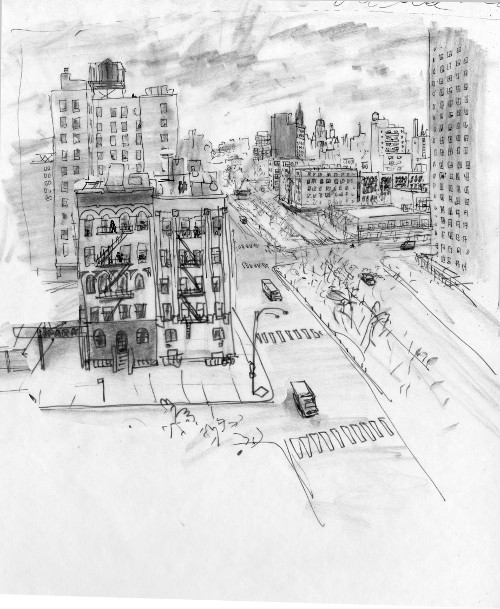

Location trivia: the setting for the sanitation truck spread is the view one sees upon stepping out onto 6th Avenue from the offices of Simon & Schuster. Much else in the book is in debt to the mile-and-a-half corridor between my apartment and studio; I was, in a sense, conducting research on every trip to work and on every trip home while making this book. The view of the New York City skyline [pictured above] is from the roof of my studio in Brooklyn. I roused myself in the predawn hours one morning — not my usual habit — to get down to the studio in time to take sunrise reference pictures for this image, only to decide later that the light looked better at around 10:30 a.m. than it did at 6:30 a.m. (But you don’t know until you try.)

Jules: When I see the police car in the fire truck/police spread, I wonder if you lingered over the wording (“the people whose job is to keep everyone safe”) when we have all these high-profile cases of police violence. Was that spread fraught?

Brian: Absolutely. And more laboring than lingering. I wanted to acknowledge those police officers who, in the middle of a global pandemic, went out to do a difficult and sometimes thankless job, and who did their jobs well and with respect for the communities they serve. But I also did not want to be oblivious to or to deny the violence we all saw last year or the realities of some family’s interactions with the police. A paragraph would have been easier to write than a line, but a line was what I felt the book would allow, and I struggled with it.

(Click to enlarge)

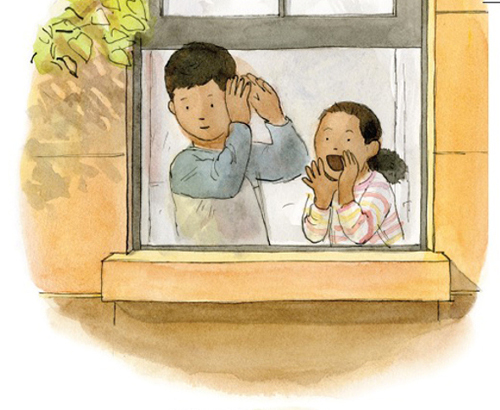

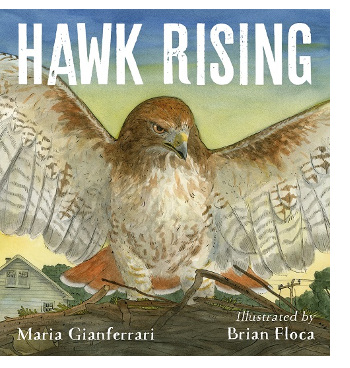

Jules: The children peering through the window on the first spread bring to my mind Hawk Rising, which makes me wonder: What books are in the works for you now? Any you are allowed to talk about?

Brian: Hawk Rising, yes! With that wonderful text by Maria Gianferrari. That’s another book about what it means to be still and to pay attention to what’s going on around us, and I’m glad one of us made that connection. Thank you.

Brian: Hawk Rising, yes! With that wonderful text by Maria Gianferrari. That’s another book about what it means to be still and to pay attention to what’s going on around us, and I’m glad one of us made that connection. Thank you.

As for what I’m working on now, the drawing table today is covered with asteroids and dinosaurs; they are for a no-holds-barred extinction event of a manuscript by Jennifer Berne, Dinosaur Doomsday, which will be published by Chronicle Books. I’m finding the book to be a delightful change of pace and mood. The late Cretaceous had its problems, but those problems are not our problems. (Look up, knock wood.)

Jules: Did you do / learn / try anything new during the pandemic that surprised you?

Brian: Like many New Yorkers, laundry day for me means a trip to the laundromat, often to the crowded laundromat. And early in the pandemic, when the sense of dread was ratcheting up a little higher every passing day, and egged on by my friend Teresa, who had just bought one herself, I ordered a Costway Portable Mini Compact Twin Tub Washing Machine — $179.99 — a contraption of a machine that allows a person to do very small loads of laundry from the discomfort of home. And so one of my pandemic learning experiences was learning to operate this appliance, which was made no easier by the user’s manual, which seemed to have traveled into English by a crooked path, and arrived in phrasings that bordered on the sibylline: “When the water level achieved prearranges position, Washes the revolution.”

And then, yes, there was bread. Which was not totally new for me, I will say, except in quantity produced. There has been a lot of bread. I nod in the direction of Jim Lahey.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: Any non-essential purchases you made during the pandemic that you want to share, given the “we’ll try not to do it again” spread in Keeping the City Going?

Brian: I bought a jacket that looked like the kind of thing I might wear for just about the amount of time it took to click “Order.” Now I have my doubts. And like the girl in the book, I have some new dinosaurs, too. I’m using all mine, though, as reference for drawings, and so no regrets there.

Jules: Anything else you want to share?

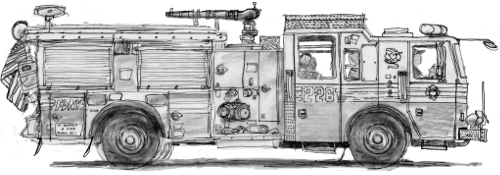

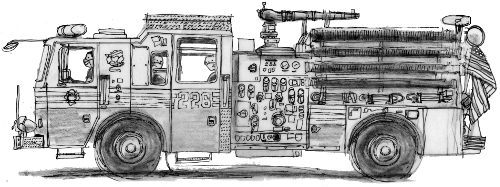

Brian: Possibly a small point, but I will say I am happy (and a little proud) that I was able to get permission from the City of New York and the U.S. Postal Service to use certain of their logos in the book. Thus, it’s an FDNY fire truck in the book, for instance, and a New York City taxi, and a USPS two-ton delivery truck, and so on. This involved not a little jumping through hoops, and maybe most readers won’t think twice about it. But it felt important to me to set these events in the city where I saw them happening, especially in the early days of making this book, when New York City was the epicenter of the pandemic here in the States, if not the world, and I’m glad I had the chance to do that. I’m grateful to the people who helped make this possible, not least everyone at Atheneum/Simon & Schuster, who displayed a strange faith that I would be able to wrangle the necessary permissions into the door before we had to go to press.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

I’d like to emphasize that I’m grateful to Caitlyn and Michael and everyone at Atheneum/Simon & Schuster for the chance to make this book, for the help in making whatever parts of it are successful work, and for all the effort and planning that went into managing a breakneck schedule (despite an illustrator with a penchant for revising until the last possible moment). How breakneck? I realized at a certain point that this is the only book I have ever made, from start to finish, between haircuts. Of course, that says something not just about the schedule, but about my pandemic grooming, too.

and that the daily become heroic.”

(Click to enlarge)

KEEPING THE CITY GOING. Copyright © 2021 by Brian Floca. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Caitlyn Dlouhy/Atheneum Books for Young Readers, New York. All other images reproduced by permission of Brian Floca.