The Great Stink:

A Conversation with Colleen Paeff and Nancy Carpenter

November 9th, 2021 by jules

November 9th, 2021 by jules

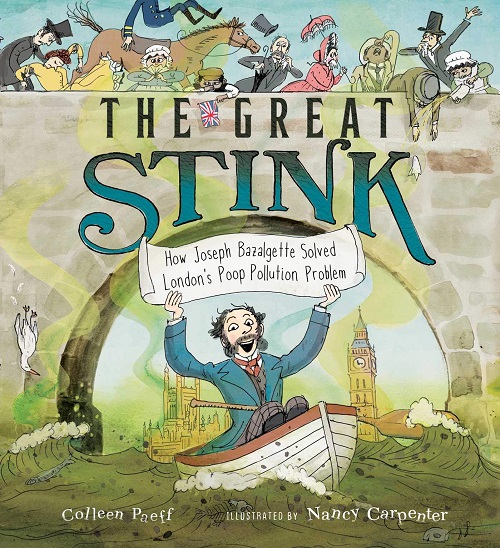

In the art-filled chat I bring you today with author Colleen Paeff and illustrator Nancy Carpenter, Colleen says of Nancy’s illustrations for The Great Stink: How Joseph Bazalgette Solved London’s Poop Pollution Problem (Margaret K. McElderry Books, August 2021): “The way she combines humor and historical detail with a dash of irreverence just feels so right for this story.” That comment stands out to me, because it’s how I’d describe this book as whole, one whose humor, historical detail, and dashes of irreverence — in both art and text — work together to tell an informative and entertaining story of just what the title tells you, what history calls “the Great Stink.”

It’s the summer of 1858 when Londoners give their problem this name. The River Thames in London is marked by a horrible smell, and everyone fears more cholera outbreaks will occur. (As Paeff lays out so clearly in the book’s opening, London has already suffered more than one bout of cholera, given the city’s issues with sewage disposal.)

But what Paeff also includes in the book’s opening is the birth, in 1819, of Joseph Bazalgette, who as an adult becomes an engineer with “dreams of making London a better, cleaner, healthier place to live.” And one of his jobs it to map the sewers of London. He eventually devises a plan for a new sewer system to clean the Thames, a marvel of engineering that saves lives. And by 1874, the “Great Stink is nothing but a smelly memory.”

I thank Colleen and Nancy for joining me today to talk about this superb piece of nonfiction. Let’s get to it. …

Jules: Colleen, let’s start with you. What made you decide to do a book about London’s “poop pollution problem?”

Colleen: Any event called “The Great Stink” seems tailor-made for kids. And that’s what Londoners called it when, in the summer of 1858, their inadequate sewer system (which funnelled the city’s waste into the River Thames) met with a historic heat wave. So first, the name piqued my interest. Then, when I discovered it was an engineer who saved the day and stopped the stink, I knew this was a story I wanted to tell.

Jules: Nancy, what was your first response to Colleen’s text?

Nancy: Honestly, my first response to the idea of a book about poop pollution was to scoff and say this is not for me. I wasn’t scoffing for long after reading the first few paragraphs. The story delves into such a serious subject — solving the problem of multiple cholera outbreaks that plagued London throughout the 19th century. However, Colleen’s playful, dry wit had me giggling right away, and I started to imagine what sort of deliciously gross illustrations the book would allow for.

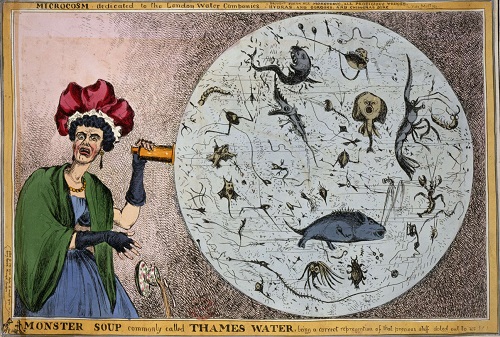

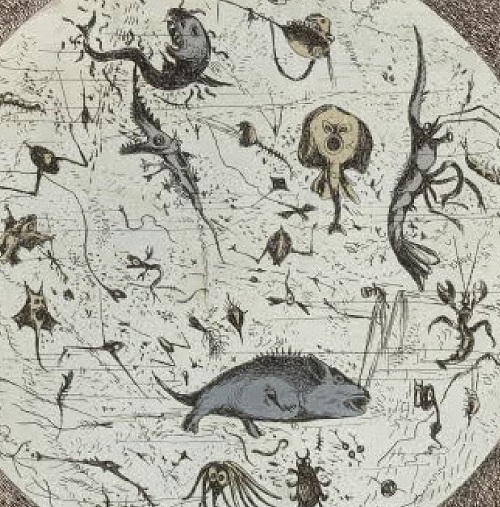

My early research guided me to William Heath’s engraving Monster Soup, which is about the contaminated water in the Thames. I loved the grotesque (yet still refined) character in the drawing. (I also hoped the monstrous microscopic creatures would find a way into the art but didn’t know how.) This was my launching point.

Jules: Wow. Look at those little creatures.

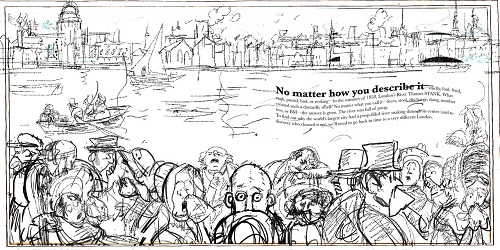

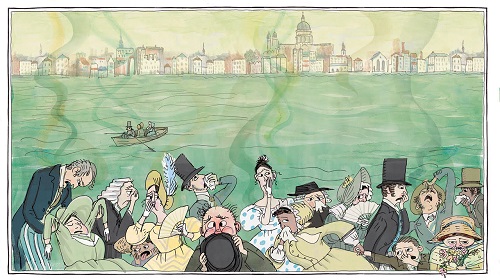

Nancy: My first sketch was for the introductory spread of London, circa 1858, where the stink problem begins. It’s pure stinky fun before the introduction of why the stench was so deadly.

What created such a revolting smell? No matter what you call it — feces, stool, discharge, dung, number two, or excrement — the answer is gross. The river was full of poop.

To find out why the world’s largest city had a poop-filled river snaking through its center, and to discover who cleaned it up, we’ll need to go back in time

to a very different London.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: Colleen, Nancy mentioned research. What was yours like for this book? Where’d you begin?

Colleen: I happened to be arriving in London for a two-month stay, just a few days after first reading about the Great Stink, and my arrival coincided with one of the days when the Crossness Pumping Station was open to the public. So my research began at a wastewater treatment plant! Seeing the huge beam engines really gave me a sense of the scope of the project Joseph Bazalgette had undertaken, and it quickly eliminated any squeamishness I had about doing a book featuring sewage. I was way too fascinated to be squeamish.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

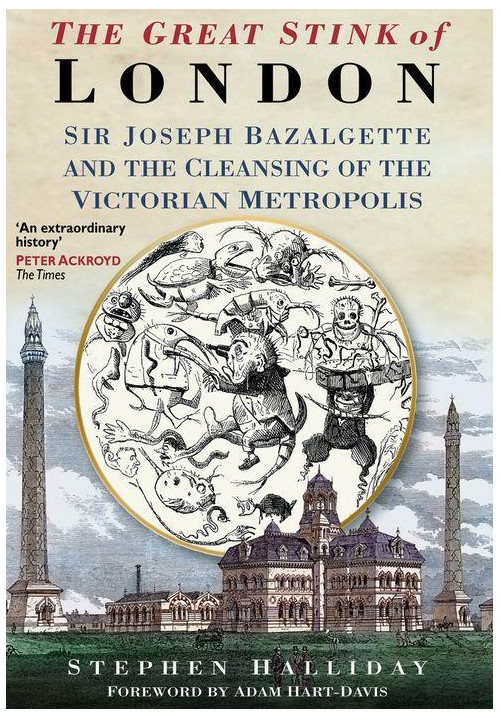

From there, I did lots of reading. Victorian newspaper articles and comics were a terrific resource and so much fun to read. And while I didn’t find any books for young children about the Great Stink, I was very lucky to find a meticulously researched book for adults called The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis, written by Stephen Halliday. That book was my most valuable resource.

Jules: What was it like for you to see Nancy’s art for the first time? Did you get to see early sketches?

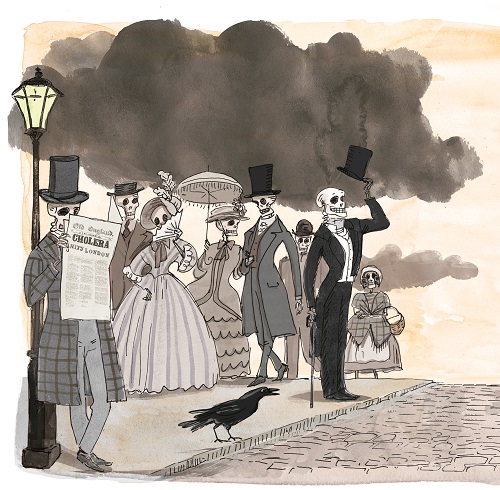

Colleen: I saw some early sketches in January of 2020, and I was over the moon! I had no idea how an illustrator might handle recurring cholera epidemics in a picture book; it’s such a dark subject. So when I saw how Nancy had incorporated skeletons into everyday scenes throughout the book, I was thrilled. What a clever way to represent the cholera victims. And the first time I saw the cover — how the letters of our names are floating in the poopy water and there’s a bird (Fainted? Dead? Who knows?!) falling from the sky — I literally leapt with joy. The way she combines humor and historical detail with a dash of irreverence just feels so right for this story.

Jules: I love those skeletons too. At what point, Nancy, did it occur to you that that incorporating them into the artwork would be a good way to emphasize all the loss?

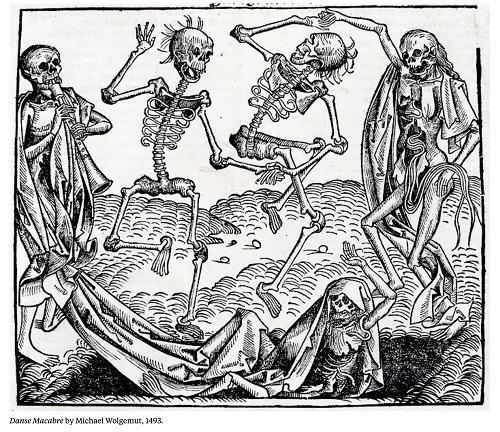

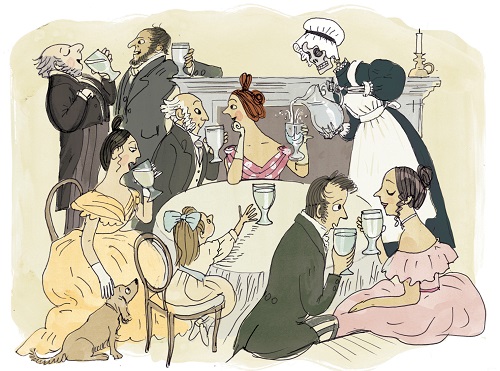

Nancy: At first, I attempted to represent cholera deaths by drawing graveyards and people gathering around gravestones. Ultimately, I felt that imagery put too much emphasis on the tragedy of the cholera epidemics. I wanted to keep the focus on Bazalgette’s ingenuity in the face of catastrophe.

If you Google “The Great Stink,” the first image you come across is “The Silent Highwayman”:

This haunting image helped me realize that a more conceptual solution to showing loss with skeletons might be more palatable for young readers, with the added bonus of being great fun to draw.

Yet much of the art showing skeletons among the living still seemed too dark and scary for a children’s book. …

(Click to enlarge)

from the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel

(Click to enlarge)

The drawing “The Aresenic Waltz” and the many Edward Gorey drawings of dressed skeletons insinuating themselves into daily life inspired me to, likewise, add skeletons to represent the looming fear of untimely death the Victorians must have felt, particularly in a time when no one knew what was actually causing cholera.

(Click to enlarge)

(from Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies)

(Click to enlarge)

But most Londoners believer their water comes from a clean part of the river. So they let any visible gunk settle to the bottom of their glasses — and they drink. In spite of the government’s fight against foul odors, London suffers its second, and most devastating, cholera outbreak. 14,137 people are dead.”

(Click to enlarge)

The rest of London is safe. The evidence is too strong to ignore. Doctors and scientists gradually begin to accept that contaminated water — not air — causes cholera.

By clearing the Thames of pollution, Joseph’s sewers are saving lives.”

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: Colleen, how did you know for this book when to stop writing? It’s a lot of info to cover. Was there much scaling back on what to include?

Colleen: There was so much I had to leave out! I would have loved to include John Snow and how he narrowed down the source of one cholera epidemic to a water pump on Broad Street. And I wish I could have added some of the hilarious complaints about the river over the years — many of them from notable figures, like Charles Dickens and Michael Faraday. But like you say, it was a lot to cover. Between explaining how the river became an open sewer; why the fear of miasmas and cholera jolted Parliament into action; where Joseph Bazalgette fit into the story over all those years; and how his sewers cleaned the river and eliminated cholera from London, I knew the story would get unwieldy fast if I didn’t stay hyperfocused on those main points. I stopped writing when I felt I had woven all those threads together using as few words as possible.

Jules: Well, and I love how you left room for the backmatter (“Poop Pollution Today”), which includes tips about green infrastructure and how can we can let “nature lend a hand,” because it’s not like we’re anywhere near solving problems of overpopulation and overconsumption in today’s world. (Note for readers: The backmatter also includes a detailed timeline, selected bibliography, and a list for further reading. Lovely!)

And there’s no plan to fix it. But there’s a bright spot in all this muck. It’s a baby boy named Joseph Bazalgette. He’s small and his family worries he won’t survive.

But luckily for London, he does.”

(Click to enlarge)

Colleen: That’s so true. I was shocked to learn the amount of raw sewage that goes into waterways in the United States every year as a result of outdated sanitation infrastructure — billions of gallons in New York City alone. Billions — in just one city! And climate change will make things worse, because sewage overflows are usually the result of heavy rains. That’s why we see signs telling us to stay out of the water after rainstorms. And it’s also why we should support funding for new sanitation infrastructure. It’s easy to look at the Great Stink and think, “That could never happen nowadays.” But cities are legally allowed to dump a certain amount of raw sewage into local waterways. They can even petition the government to increase that amount — and many of them do. It’s mind-boggling.

Nancy: The first time I read Colleen’s manuscript was in 2018, and the environmental themes leapt out at me. Bazalgette’s struggles with Parliament and its obsession with expense, in the face of dreadful human suffering, is exactly what we deal with today. Then when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the history of London’s cholera epidemics and the connection to today became uniquely salient.

Jules: Nancy, what is it that you love about working in watercolors? And tell me about deciding to make these wonderful endpapers as you did. You could have put any number of things on them. I love them. (They are not pictured here, but that’s all the more reason for readers of this post to go get their hands on a copy of this book.)

Nancy: Funnily enough, I don’t like working with watercolors, but I love the spontaneous, clean, transparent effect of watercolor with pen and ink drawings. I’m not the masterful watercolorist I’d like to be, so instead I add layers of scanned watercolor washes to my drawings, using Photoshop. This gives me far more flexibility to change and undo color mistakes without ruining the pen lines.

The endpapers were inspired by the engraving Monster Soup I mentioned at the beginning of our conversation. Early on in my sketching phase, I knew I wanted to include these funny, macabre river monster microorganisms somewhere, because they go so well with the skeletons. The endpapers became the perfect solution.

THE GREAT STINK: HOW JOSEPH BAZALGETTE SOLVED LONDON’S POOP POLLUTION PROBLEM. Text © 2021 by Colleen Paeff. Illustrations © 2021 by Nancy Carpenter. Published by Margaret K. McElderry Books, New York. All artwork here reproduced by permission of Nancy Carpenter. Photographs reproduced by permission of Colleen Paeff.

Great interview and a fabulous book for all ages. A book that can be read to your children and generate discussion. Every time I look at the illustrations I see something that I missed!

Wonderful blog. I love this book! HGreat illustrations