The Waiting Place

May 10th, 2022 by jules

May 10th, 2022 by jules

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

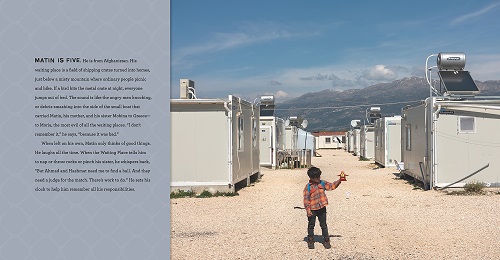

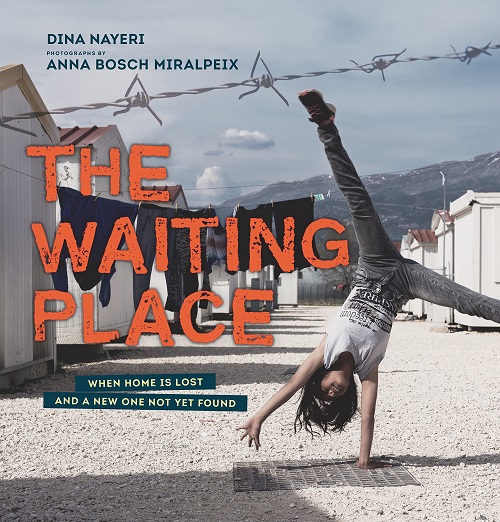

You’d be hard-pressed to find a children’s book this year as driving, urgent, passionate, and deeply felt as The Waiting Place: When Home Is Lost and a New One Not Yet Found (Candlewick, May 2022), which comes from author Dina Nayeri and photographer Anna Bosch Miralpeix. The book chronicles Nayeri’s and Miralpeix’s 2018 visit to Katsikas, a refugee camp near Ioannina, Greece.

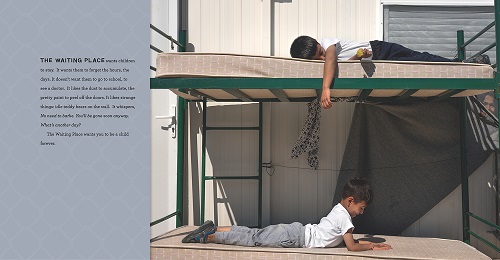

Nayeri and Miralpeix focus on the daily lives of a small group of children at this refugee camp. Compellingly, Nayeri makes the camp itself, which she calls the Waiting Place, the book’s antagonist — or, as she shares in this video, its very villain. The Waiting Place is an in-between place that welcomes you, but inside is a “dreary, lazy encampment where there is nothing to do but drift.” Nayeri does much with tone and mood here, giving an eerie motivation (what she calls in the video a “shadowy uncertainty”) to this antagonist that is “always stirring mischief” and eager to rob children of, essentially, their joy:

The Waiting Place … wants more children and mothers and fathers. It doesn’t want you to visit the nearby lake, to hike the frosted mountain, to learn your new language, or to work or build or learn. It craves your hours, weeks, years. Here is a place that always sees you, it whispers in the night. You must wait. Any day now. Tick tock. Why bother with plans? Sit, sleep, fight. Don’t be caught unpausing.

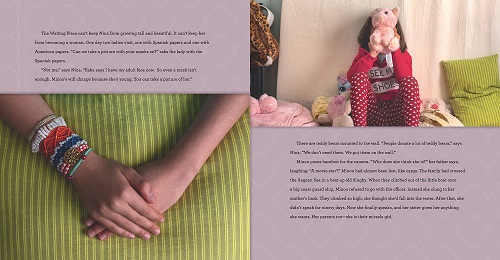

Readers meet a group of children from Iran and Afghanistan, many of them siblings. We read about their struggles, dreams, hopes. We read about their battles — sometimes with one another and, most of the time, with the malaise that the Waiting Place is so eager to instill as a part of their daily lives. Nayeri and Miralpeix bring readers the particularities of these children — Nayeri with her prose, which is at turns powerfully plainspoken and evocative, and Miralpeix with her vivid, full-color photographs — and these details make the children come to life on the page. About Matin’s older sister, Mobina, we read that she settles in front of a tablet and:

… wants to watch the satisfying video, the one that brings the calm feeling. It shows how toothpaste can remove crud from an iron, how vinegar cleans a kettle, how baking soda whitens old sneakers. She also likes things fitting into slots, things being smoothed, things being colored in. Mobina is almost eleven and very good with the computer. She misses hers, left behind in Afghanistan.

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

In the book’s creepiest, most abrupt, and most incisive note, we read about Camp A — the original camp, a “ghostly place”: “Nobody talks about it.” In another more triumphant note, we read about Shokrieh’s older sister, who has in her hair a lightning-bolt scar from when her house was bombed. She matches it with a shirt featuring a lightning bolt: “Her scar is an accessory now! It’s part of her brave new identity. The Waiting Place doesn’t like that one bit.” There are also “signs of joy” throughout the camp, such as a fence painted in bright colors, what Nayeri calls “proof that the Waiting Place is losing.” When Nina encourages her younger sister to “work, to make things, to learn,” the Waiting Place fumes. It doesn’t like “this kind of talk.”

It doesn’t want them to go to school, to see a doctor. …”

(Click spread to enlarge and read text in its entirety)

In an afterword, Nayeri shares her own personal experience as a refugee: “I am a refugee. My mother is a refugee. Every war, famine, and flood spits out survivors. Every village that sits atop oil, or finds itself in the way of someone’s ambition, sees its peaceful families robbed and cast out.” In quoting Roland Barthes, she writes about the terror of making someone wait, “the constant prerogative of all power.” She writes about feeling this power firsthand when she herself lived in a refugee camp as a child. She writes about how she and Miralpeix interacted with the children at the camp, how they played with them. And she writes about internal displacement; asylum seekers; leaders who “lie with metaphors”; the folly of refugee caps (“How can you put a cap on need, on human duty?”); the lost time and dignity and purpose of refugees who wait; and her desire for “luckier children” to read about the children at such Waiting Places. After all, no human is exempt from the possibility of being displaced at any time.

This rallying cry of a book, a pressing call to action, puts a human face on a human failing to help displaced children. Get it. Read it. Share it.

THE WAITING PLACE: WHEN HOME IS LOST AND A NEW ONE NOT YET FOUND. Text and photographs copyright © 2022 by Dina Nayeri. All images reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, Massachusetts.