The Velveteen Rabbit: A Visit with Erin Stead

May 12th, 2022 by jules

May 12th, 2022 by jules

(Click image to enlarge)

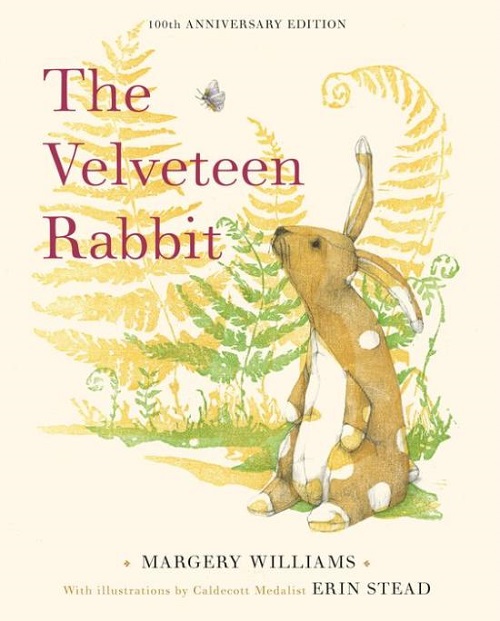

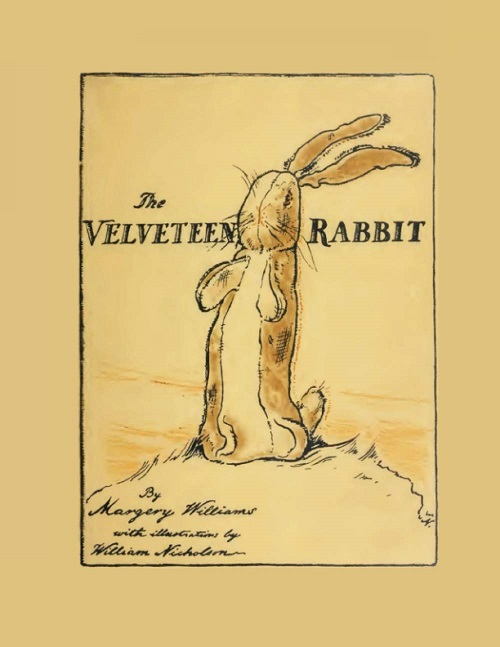

When I was a child, I read Margery Williams’s The Velveteen Rabbit (or How Toys Become Real), originally published in 1922, over and over again — so often that I can still recite the book’s first paragraph by memory. I remember feeling chilled by the description of Nana, who “ruled the nursery.” I remember her “swooping about like a great wind” and being short-tempered and careless with the toys. It was my first lesson in how an author can depict so much about a character via their actions alone. I remember the Skin Horse’s words. And I was mesmerized by the fairy.

A reader can certainly have a nostalgic longing for a book they read as a child, but is the book good? I am all the time talking to my picture book grad students about this — about not letting that kind of thing get in the way of evaluating a book on its merits. For me, this book endures. This is why I was excited to see that Erin Stead has illustrated the 100th anniversary edition of the book, released in April by Doubleday. Erin put it well in this NPR piece: “The part that we all remember about talking about what’s real – that really carries with you for the rest of your life with all of the relationships you have, all the friendships that you’ll make, and all the times that people aren’t necessarily kind to you. There’s a lot of insecurities. There’s a lot of figuring out how you belong. It’s hard to shake a story that’s that honest.”

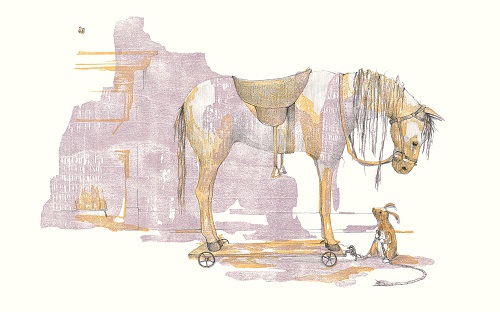

Stead’s illustrations bring much to this century-old tale. Case in point: The spread right after the Rabbit meets some real rabbits, who tell him he isn’t real. It’s a moment for readers to take a moment, take a breath. But then Erin talks about that a bit below, because she visits today to talk about creating the artwork for this book. So, let’s get right to it so that she can tell you about it. I thank her for sharing.

Jules: When this project came to you, were you already a fan of the book? Was it a story you loved as a child?

Erin: I guess the first thing I should admit is that Phil and I were the ones who brought the idea to illustrate the 100th anniversary of the story to the editor, Frances Gilbert. We were sitting around one night at the beginning of the pandemic with a toddler, alone and fretting about the future, just like everyone else. We talked about things we’d like to do — the type of books we’d like to make as long as people let us. Illustrating a classic was a part of my list, and The Velveteen Rabbit was the one I was hoping to do. So, as we were sitting there talking it all over, I drew a little rabbit meeting real rabbits, and we sent the idea off to Frances of Doubleday Books for Young Readers.

Frances was our editor for the Twain book we did together, and she was wonderful to work with. She was also the editor a few years ago of a clothbound version of the original edition, and she was careful to restore the original illustrations in that printing. Since we knew she cared for the story so much and we had duped her into working with us previously, we came to her with the idea.

The story of The Velveteen Rabbit has always followed me around, I think. I did love it as a kid, but I think grown-ups tend to remember it as being a story for a little kid. I don’t think it is one. I think it’s a story for when you are just graduating from little kid, that age when you are old enough to know that there is a chink in the armor of your belief in magic. You can tie your shoes and get your own snack, and you know that there are good things about being bigger — but sad things, too. I also think it’s a story for grown-ups. (A lot of the best things for kids are.) I was hoping to make an edition that an adult would read and give to their friends, particularly after the last few years we’ve all had. I hoped this edition would look grown-up enough to be taken seriously — that it looked like it respected the reader, whether they are eight or 80 years old.

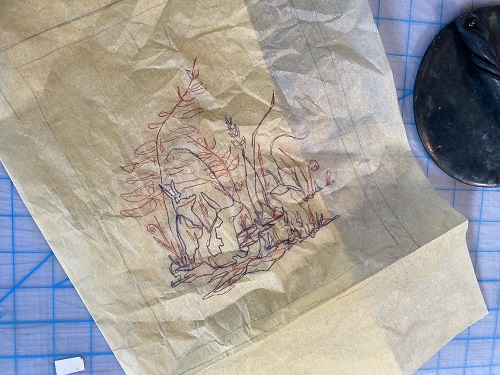

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

This is a long-winded way of saying, I do love this story. It was a part of my Caldecott speech, my AP art history exam in the high school where I met Phil, and my collection of books on tape I’d listen to on the carpet of my childhood bedroom. The story has held the hands of children who have their own members of their Real world and has taught parents to respect Real, even if they can no longer remember that time themselves. That’s why it’s 100 years old and in countless editions.

in all the pictures of the book as an underpainting.”

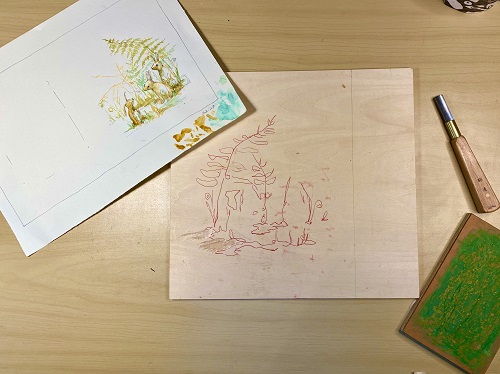

(Click image to enlarge)

Jules: What’s your favorite thing about Williams’s writing in this story?

Erin: I’m concerned this is one of those questions I’ll have a better answer for in a week, but here goes. I love how the human characters really aren’t that important. The boy is kind of important. We are told that time passes and they play together. The bond is described but left fairly open. All that playing they do, all the exploring — that’s theirs. She seems to know that children reading this story don’t need to hear about all that romping and pretending, because it’s already their daily life. But the highs and lows in the story tend to come when the Rabbit is without the boy. The Skin Horse moment that everyone remembers is during a quiet pause in the nursery. The meeting with the real rabbits happens when the Boy leaves the Rabbit behind. We don’t know much about the Boy. She grabs you by knowing you probably had your own version of the Velveteen Rabbit. That’s what Williams is talking to you about.

The adults are mostly useless. Exasperated, unsympathetic, and hurried. All those things can be really cutting to a kid.

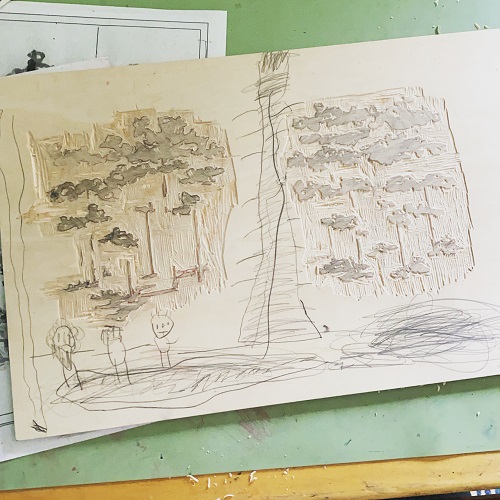

(Click image to enlarge)

Jules: What was it like to take on an older, esteemed story? What, if anything, surprised you as you created the illustrations for it?

Erin: This story has been re-illustrated a lot. I was concerned about making an edition that would be worth publishing, because there are some really good ones out there. It is nerve-racking for me to take on any book, frankly. What surprised me was how pleasantly these images came to me, because it was in the midst of some turbulent times. I was often at my desk to start my work day once everyone else was asleep, after a day of pandemic-parenting or attempting to move houses, or check on my parents because one of them was very ill and the other one was taking care of him. The last few years have been a lot for everyone. For me, it’s been hard to feel creative, so I was surprised when the images weren’t hard to find.

so she doesn’t dent the soft wood.”

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

Jules: Was it up to you which parts of the story you illustrated?

Erin: Yep! More about this in the answer to a different question below. But generally speaking, I am very possessive about layout and pacing. It’s one of my favorite parts about storytelling.

Jules: What’s your favorite part of this story and what was your favorite part to illustrate?

Erin: I’m answering this under the assumption we can all agree the following is a Great Moment in Children’s Literature:

It doesn’t happen all at once. You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t often happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all because once you are Real, you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.

So, other than that entry into the canon, my favorite part of the story … well, this is actually difficult to answer. A lot of moments stick out. What I appreciate about the story is that she doesn’t shy away from a lot of different emotional turns within a 40-page book. The reader can experience loneliness, loss, worry, enchantment, the adolescent feeling of not fitting in, and the love of a best friend.

” … once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

(Click to enlarge)

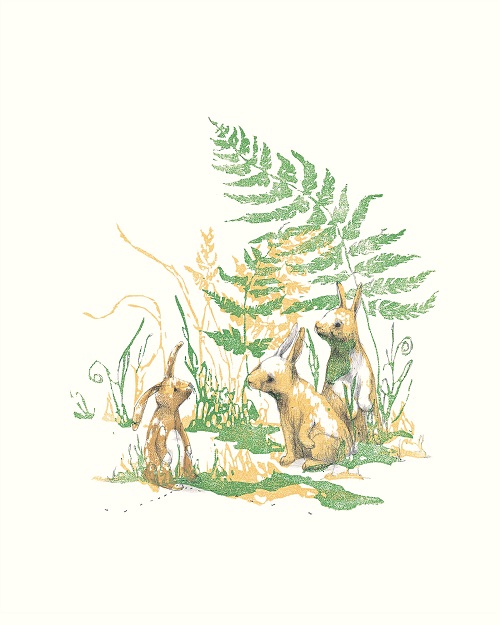

My favorite part to illustrate was either the Skin Horse in the nursery or the series where the Rabbit meets the real rabbits after being left out in the ferns.

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

And all the time their noses twitched.”

(Click image to enlarge)

I illustrated a pause right after that devastatingly awkward moment, where we spend a full spread in the woods with the Boy taking him home. I enjoyed drawing that moment out of the text and forcing the reader to pause there.

(Click image to enlarge)

Jules: Can you talk about your decision not to illustrate the fairy, at least in a distinct or literal way? (I see there’s a butterfly on the page following the fairy’s appearance.)

Erin: Did you ever read a novel as a 10-year-old that was illustrated and you thought, oh, that’s not how I thought that character would look? When I’m illustrating for a slightly older audience, sometimes I make the decision to back out of the room and let the reader decide what this part of the story looks like. I am not a caricature-type illustrator. I tend to get too detailed in portraiture. Sometimes I think this aids the story, and sometimes I think this would get in a child’s way. For this fairy, who is a kind hero, I want them to look however the reader might imagine them. The author provides a good deal of description in the writing. I didn’t think I had to be the illustrator to force her hand.

Jules: I see on the copyright page that Phil assisted with book design. Is that right?

(Click image to enlarge)

Erin: Both Phil and Martha Rago helped me with the book design. I had some pretty specific ideas going into the book — some which made it through (the layout and design) and some that didn’t. (I wanted the trim size to be much smaller but was told this was a bad idea.)

One of the things I like best about illustrating children’s books is deciding on the pace and layout of the story within the limitations of the bound book. I think your readers already know this, but books have to be bound in signatures (a signature is if you take a bunch of paper and fold it in half), usually containing eight pages for picture books. Most picture books you see are 32 pages total. Some are 40. Then 48, etc., etc.

When Phil and I were making the Twain book, I manipulated the layout as though it were a picture book, even though the text length was quite long. I added pauses, full spreads within a chapter to try to slow the reader down or for emotional emphasis, and pages that were almost entirely blank, also to force the reader to pause. Unfortunately, for Phil and Martha (who was also the designer on the Twain book), this makes the layout somewhat difficult. I would want a page to end after a certain sentence but still fit within the design rules of the book. You have to do a lot of kerning and fiddling to get this right.

Then we did the same thing for The Velveteen Rabbit. I knew the layout I wanted in my head but wasn’t sure it would fit within the formality of the text design I was hoping for. So, once our toddler was asleep, I’d force Phil to stay up late at the computer working on line breaks while I stood over his shoulder (unhelpful), telling him how I’d like it to work. Although I am somewhat versed in book design, Phil actually went to school for it and continues to be more proficient at the nitty gritty of it all. I am more of a grumpy editor about the whole thing. Martha would then clean up our work, fine-tuning it or helping me when I couldn’t quite find the right typeface.

I really wanted this book to be read. I think a lot of people have a version of this story in their head or on their shelf but have never actually made it through the story. I was hoping by designing the type and layout the way we did, that people would sit down and read the story. It’s a storybook, not necessarily a picture book.

Jules: Anything you wanted me to ask that I didn’t?

Erin: I noticed while I was doing research for the book that Google predicts you’ll type “Why is the Velveteen rabbit so sad?” I’m assuming this is some sort of standardized test question somewhere, which is why it’s so Googled.

It is sad. It’s also joyful, worrisome, strange, and comforting. It’s okay that it’s sad. I am often sad. I know that part turns off a lot of adults as well as the children who were introduced to the book at the wrong time. But within the book is the reminder that even when you feel alone, you’re not alone. What a good human story that is, brought to you by a little toy rabbit.

THE VELVETEEN RABBIT. Jacket art and illustrations © 2022 by Erin Stead. Published by Doubleday Books for Young Readers, New York. All images reproduced by permission of Erin Stead and Doubleday Books for Young Readers.