Keeping the Fires Stoked with Antoinette Portis

August 18th, 2015 by jules

August 18th, 2015 by jules

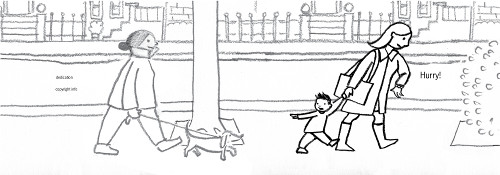

(Click to enlarge spread)

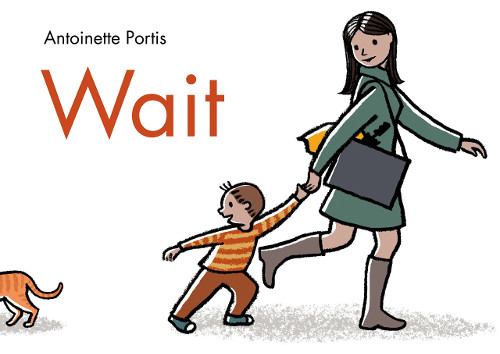

Author-illustrator Antoinette Portis joins me this morning for a lovely, long chat before breakfast. Last month over at BookPage, I reviewed Antoinette’s newest picture book, Wait (Neal Porter Books/Roaring Brook Press, July 2015). That review is here.

Today, Antoinette talks all about the book and its evolution; her experience as a Sendak Fellow; the fine art of being content with discontent; her upcoming picture books (with art from each to share!); and much more. I thank her for visiting, and let’s get right to it.

[Please note that the colors in the larger versions of each image, should you choose to click on them, are slightly brighter than they appear in the book.]

Jules: Hi, Antoinette! I’m not going to ask you about how the story of Wait came to you, since you covered that in the Horn Book Q&A and the Q&A at Publishers Weekly. I do want to ask about this, which you typed to me in an email when we were chatting earlier:

I don’t think of myself as an illustrator per se, but a visual communicator or a visual storyteller. I generally don’t use drawing as a way to come up with ideas. I get ideas, and then I sketch them out to communicate them. I think my idea machine is on the language side of my brain. Then the drawing side kicks in and fleshes things out. It’s taken me a while to figure out that this is my particular process.

Is this something you discovered during the Sendak Fellowship, by chance? Or earlier?

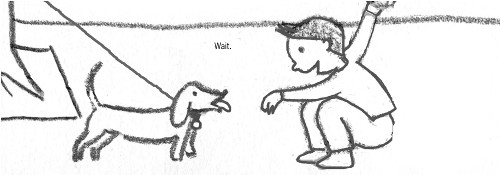

(Click to enlarge spread)

Antoinette: When I was in art school, my best friend always carried around a sketchbook and drew everywhere she went. In high school, I used to carry around a sketchbook everywhere I went, but I wrote in it. Anyway, my friend’s dedicated drawing practice was a rebuke to me. I wasn’t going to be a poet. I was heading toward being a visual artist, so why didn’t I draw all time? I started carrying a sketchbook and drawing regularly. But mostly, I drew to learn how to see. It was more often a turning outward, not inward.

At the Sendak Fellowship, it seemed like my friend Rowboat Watkins, like my college friend, also used drawing to bring forth ideas. His hand told him stuff about his interior life. It looked like drawing was his connection to inspiration, to his internal idea factory.

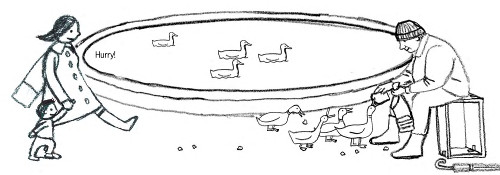

(Click to enlarge spread)

That has always seemed like the way artistic process is supposed to work. It’s taken me a while to accept that there are different ways of getting ideas out and onto paper. So, I have gradually come to make peace with, and maybe even relish, my own process. (Judging it and rebelling against it did not prove to be helpful.)

So, I mostly use writing to generate ideas. It doesn’t matter which comes first, words or image, because my books are going to have both. The two strands, at the finish, are going to synthesize into a whole.

Once I immerse myself in the drawing phase, the writing part of me shuts up and I get into that flow where visual ideas just seem to show up of their own accord. Working on Wait, the pictures start thickening up: visual motifs, subtext, foreshadowing, color all started to add little tiles of meaning, like building a mosaic.

(Click to enlarge spread)

Each small detail serves the overarching theme, and the whole adds up, one hopes, to a piece of visual literature.

That’s what I’m striving for anyway. It’s a frigging thrilling goal. What picture books are capable of—the endless possibilities—lights my brain on fire.

Jules: Yes, it’s that “seamlessness” of text and art that Sendak once spoke of. Such a unique art form, these picture books.

I am not going to pry into your time with Sendak at the Fellowship, but may I ask about a piece of advice that he gave you that really sticks with you?

(Click either image to see spread in its entirety)

Antoinette: Maurice talked a lot about making books that had depth and meaning. He thought every book that gets published should matter, should say something children need to hear. He charged us with carrying on his mission — making books that authentically reflect the experience of being human.

So, no pressure. No pressure at all.

I guess what struck me the most about Maurice is that he was the living embodiment of what was great about his books. He was openhearted, deep, funny, honest, poetic, iconoclastic. When you met him in person, you saw that you had already met him in his books.

He wanted us, with him, to fan the flames of rebellion against blandness. He expressed his despair over the growing tendency among publishers—as more and more houses become divisions of giant, publicly traded media conglomerates—to regard books as mere consumer products that exist only to help the bottom line and increase shareholder value.

(Click to enlarge)

I’m certainly glad this isn’t universally true. I’m glad there are true believers out there, passionate about making great books.

It was an amazing experience to have Maurice as a friend. He was someone you could laugh and cry with, usually both in the same conversation.

Another thing I learned, something that Maurice wasn’t consciously trying to teach us, was that all artists have to deal with their own sense of failing to meet their internal artistic standards. I may wish I could make a book as great as Where the Wild Things Are, but Maurice wished he could etch like Rembrandt, write a symphony like Mozart or a novel like Herman Melville. The man had seriously high standards. It made me realize that having goals far beyond what you can achieve is useful. Those goals lay out plenty of road ahead to travel.

(Click to enlarge)

With these thoughts on my mind, the day after I left the Fellowship I was in New York at the big Matisse retrospective at MoMA. There I saw a famous conceptual artist whose own retrospective I’d seen in L.A. before I left for the Fellowship. I went up to tell the artist how much I loved his work. He was standing in front of a quintessential Matisse etching—just a few casual, perfectly-placed black lines on cream paper—and there was a luscious plate of fruit. He tipped his head toward the etching and said, “Doesn’t it make you want to kill yourself?” I said, “I saw your show in L.A. and it made me want to kill myself!”

(Click to enlarge)

So, there you go. What hope was there for me, lowly struggler, if my idols aren’t satisfied with their work?

We all think: If only I were Maurice Sendak or Mr. World Famous Conceptual Artist, then I’d be content.

But, no, you wouldn’t be.

You’d be wishing, always, to be more, to do more.

So, I am learning to be content with discontent. It keeps the fires stoked. There’s so much still to learn.

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: That makes a lot of sense to me. I feel like I push myself in that way—I often think in my head of the person I’d like most to impress when I’m working on a project—but I figured I was being too hard on myself with my high standards. This is a good way to look at it.

I always like to hear stories about how generous and open Sendak was, because I think right before he died he got a bad rap sometimes in the press. He was portrayed as a grouch. Now, I never met him, and he was sometimes publicly grumbly about publishing trends, but in his career, he helped open doors for so many young, up-and-coming artists. And he had so much respect for children and their emotional lives. I see these things as very generous.

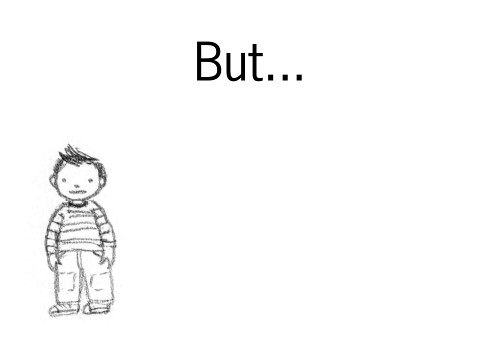

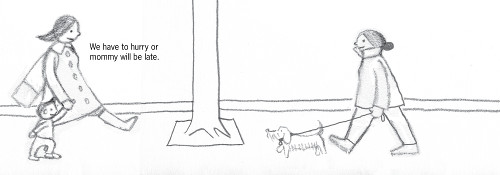

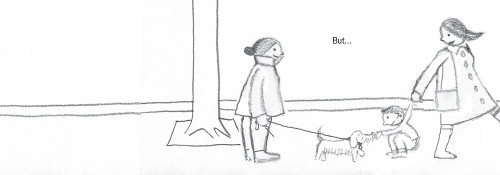

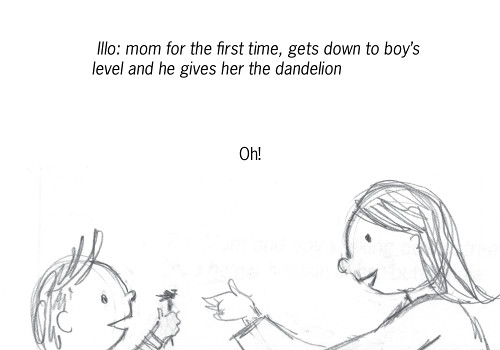

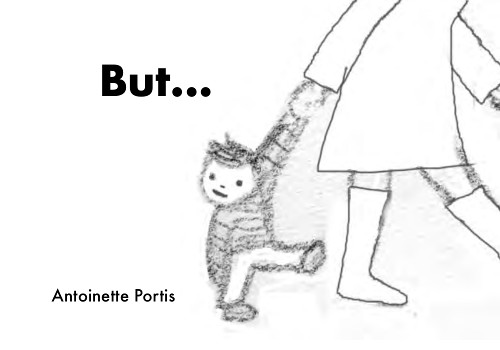

Okay, to the book, specifically! Can you talk about the drafts you went through? We can see here in the images you’ve sent that the story began back in 2010 and was once called But …, right? Can you talk about the story’s evolution?

(Click to enlarge)

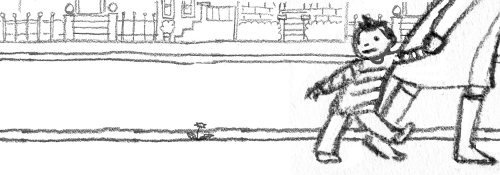

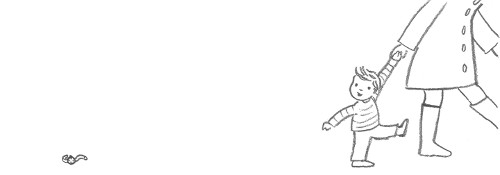

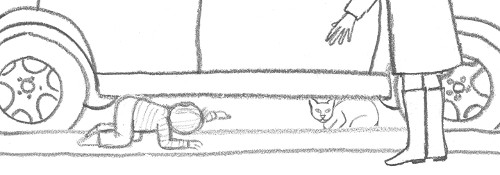

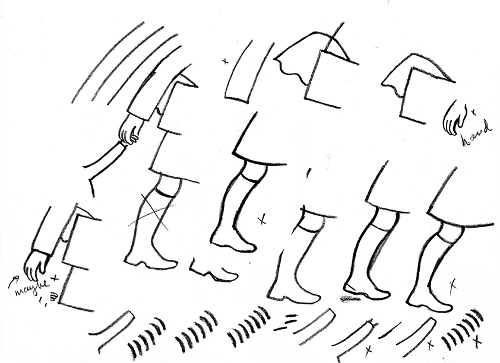

Antoinette: Wait kind of wobbled into existence, as most of my books do. I’d seen this moment happen — a little boy pulling away from his rushing mom to look at something interesting and being kind of yanked back on course. And I knew it had the makings of a picture book.

But the idea didn’t come with a built-in ending. Some ideas come with an arc, like Froodle. I knew what the crisis point was, so I knew where the story was headed.

(Click middle images to enlarge)

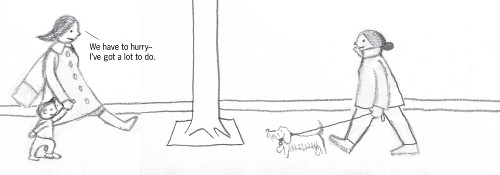

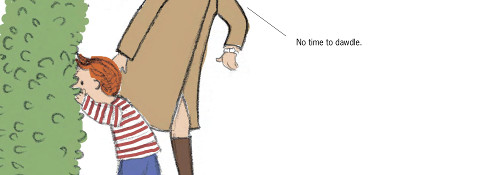

But Wait felt more like Not A Box — episodic, more like a straight line than an arc. They’re both about the perpetual back and forth between adult and child.

So with Wait, the tricky part was coming up with an ending. I wanted to end on a moment of connection. I wanted to honor those moments as a parent when you slow down and let your child show you how to just be.

I first dummied it up as But…. Grammar provided a perfect analogy — a child’s agenda is a subordinate clause. I worked on various iterations in my writing group. The But… version showed the mom rushing, but only the boy spoke. Another version had the mom saying, “Let’s keep moving,” “Mommy’s in a hurry,” etc.

I played around with different variations until it was clear to me that the mom should say only “hurry” and the boy should say “wait.” The counterpoint of the two verbs emphasized the tug of war between them.

(Click all but first image to enlarge)

Back to the issue of the ending: The funny thing is, as a writer, I had thoroughly put myself inside the head of the child. Kids take it for granted that they are tugged around the world without rhyme or reason. That’s just the way life is. So, I had two versions of an ending, both from inside that context. In one, the mom, in her rushing, drops her watch and the boy is the one who notices it and saves the day. In the other, the boy picks a dandelion out of a sidewalk crack and gives it to his mom and she stops for a moment before rushing on. Neither of those versions got a go-ahead.

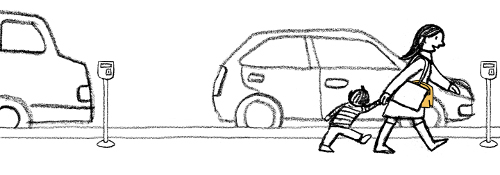

But I took good advice from smart people who spurred me to come up with a more dramatic ending. They asked questions that are important for a storyteller to ask: Where is the mom rushing off to? Why is she in such a hurry?

So, duh, I needed to show the immediate goal the mom was rushing toward, so that her stopping had more impact. When I knew where she was going, I could build clues into the illustrations that hint at what the “ticking clock” of the story is: catching the train. And then I knew that the last thing the boy notices had to be something worth missing a train for. A double rainbow, something rare and remarkable.

(Click first seven images to enlarge)

Figuring this all out was a lesson in story-building.

Maybe it will be easier next time.

p.s. I feel like I earned the right to use a double rainbow — after a storm, one arched over my house. Nature gave it to me. And a gift like that, you gotta use.

I just saw on Facebook that you teach a class on picture books. Can I ask where? It seems like one could learn a lot from teaching.

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: Oh, I teach one course for the The University of Tennessee’s Information Sciences program (library school), and it’s a grad course on picture books. My official title is Lecturer. I don’t have a doctorate (yet?), and I am not even a part-time teacher. I just teach this one course for now. Needless to say, I love it. It looks at picture books in a curricular light (meaning, one week we’ll talk about good poetry picture books; then, nonfiction; then, folktales; then, international books, etc.), and it’s not, say, all about the art of the picture book. But I do open the course by talking about how we define picture books and how they work. I enjoy it.

And, yes, I learn a lot from teaching.

Have you ever taught?

As for the shape your story ended up taking, all I can say is that it’s just right. Also, every time I hear picture book authors talk about their craft, it amazes me anyone can ever get a picture book written. That sounds so goofy and over-earnest, and I guess I’m being hyperbolic. But I had to write one for a grad course once (fiction), and it was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. It’s such a difficult thing to shape a story right and then craft the words. (This makes it all the more frustrating when you hear the average person on the street talk about how easy it must be.) I doubt many picture books arrive fully-formed in any author’s mind. And I think it’s fascinating to see the path to how an author or author-illustrator got there (like you’re sharing here today), even if what matters in the end is the final product, of course.

(Click to enlarge)

Antoinette: Are you thinking of getting or in the process of getting a PhD? That sounds intense. A lot more intense than making a picture book.

I was just at the SCBWI conference, and there was a lot of talk about people who don’t write picture books thinking they’re simplistic and easy to write. It definitely takes more time to write a novel than a picture book, but it doesn’t mean picture books are a breeze. They can be as deep, complex, and nuanced as any form of art. Just in an extremely economical way. There’s a quote that seems apropos (it’s been attributed to many writers, but apparently originated with Blaise Pascal): “I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.”

Picture book-making gets intense when a project isn’t working. Or when it was working and then one little revision makes the whole thing fall apart. I’ve come to recognize that as part of the creative process. I noticed this phenomenon when I worked at Disney as well. You hit a glitch and all the work you’ve done so far seems wasted, suddenly irrelevant. But you struggle through to a solution that brings the whole thing to fruition, usually in a different way than you anticipated. Like you might have to ditch something that seemed absolutely essential at the beginning of the process.

(Click to enlarge)

Then there are the ideas that just don’t take you all the way there. The problem is, midway through the tangle, you don’t know if the idea is inherently unsuitable, or you just haven’t yet figured out how to make it work. You don’t know whether to press on or push the eject button. That’s why a writer’s group is so great. When you feel discouraged, having someone say, “Keep going, you’ve almost got it” makes the difference between a stack of abandoned, dead-end versions and a book that works.

Some ideas I have had to chuck for now, hoping I’ll be better equipped to take them on someday. I heard Neil Gaiman speak once and he said he had the idea for The Graveyard Book years before he wrote it. He felt he wasn’t a good enough writer at the time to be able to do the idea justice. But he learned and grew as a writer, and one day he was ready. And how wonderful that book is!

I’ve never taught, though managing creative people for many years sometimes felt like teaching. Doing these interviews has been a learning experience. I’ve been driven to take vague feelings, musings, and half-formed intuitions and form then into cogent thoughts. Even if no one else learns anything from what I’ve said, I did! I imagine teaching is like that. You don’t even know what you know until you start articulating it as a lesson plan. We take our own life and work experience for granted. It’s just wallpaper. But when you start really looking at that wallpaper, it comes to life. You can pluck those roses right out of there and share them with someone else.

(Click to enlarge)

Jules: I used to think I’d want to teach full-time in some sort of postsecondary setting (college or university, etc.), but now I’m not sure I’d want to do that full-time. I still have to think about that. I think that would determine if I ever got a PhD (to answer your question).

Yes, teaching forces us to articulate these thoughts wandering around our heads, and that is always good.

Can you talk a bit more about working at Disney? If I knew that, I failed to remember. What did you do there?

(Click first image to enlarge)

Antoinette: I freelanced at Disney Consumer Products (DCP) for three days, working on an ad for the Pediatric Aids Foundation for which Disney was doing a charity event. There were so many acronyms, private lingo, and meetings; I kind of thought Disney was a cult.

I’d definitely seen the power Disney movies exert over little girls. My daughter was four when The Little Mermaid came out. If we were in Target, she could spot that teal and purple packaging from 200 yards away, and then … the whining! the begging!

I ended up working there full-time on the Disney licensing business. A business I’d never heard of — I thought Disney made everything they sold. I figured I’d be at Disney maybe a year, tops, but I stayed almost nine.

My boss hired me and other designers whose tastes she trusted with the goal of elevating the design standard of licensed products. And we did that. I was able to hire such talented people, and they astonished me every day. Some days my mouth hurt from smiling so much.

It’s hard to explain what I did there, because like me when I started there, nobody knows what licensing is.

Skip this paragraph if you don’t care what licensing is (I don’t blame you): Certain product manufacturers pay a fee to intellectual property developers, like animation studios (or children’s book authors) to use that IP on their products. All the products you see outside the Disney parks and the Disney Store are designed, manufactured, and distributed by licensees, not by Disney itself. So, for every Disney movie for which there will be consumer products, Disney makes a source book, called a style guide, for all the licensees to use. The intention is that all the product out there will have a unified look and reflect the film faithfully. No more weird stuff out there like the Mickey Mouse dolls from the ’30s that looked like giant rats.

Disney provides character art, graphic design themes and elements, color palettes, etc., all approved by the filmmakers. It’s easy to understand that Disney would want the characters on tee shirts to be accurate renditions of the characters you see in the movie, but that same attention extended to graphic elements too. E.g., if Snow White was framed in flowers on a dress bodice, then the flowers had to be based on flowers from the film, drawn in the style of art in which the film was drawn. You couldn’t put Eyvind Earle’s Sleeping Beauty flowers with Snow White or vice versa. Verboten. (My boss was the first one to suggest that perhaps all the princesses could be grouped together, but that idea was vetoed. Disney wasn’t ready to loosen the reins that much. But it did happen eventually, as you can see.)

I managed one of several teams of designers and illustrators, who made style guides for new films. We got to work with animation from the beginning of the film’s development. The illustrators, called character artists at Disney, learned from the animators how to draw the characters on model. They ended up knowing the characters’ personalities so well they could draw situations and interactions that weren’t in the movie, but felt true to the movie. The designers got to see all the development reference the animators and background artists were using: color stories, props, design elements, and the design influences of the film’s art direction.

Just to give you one small glimpse into our process of working with the animation studio, one task was to translate the character colors into PMS colors (a universal color system for printing and products) for the style guide. For example, for Hercules, the filmmakers chose a grayed mauve for Megara’s dress. We asked permission (this was like asking the Pope if you could get divorced) to brighten it up to a more kid-friendly shade, since the idea was for little girls around the world to be trotting off to bed in their irresistibly appealing mauve Megara nightgowns and mauve Megara slippers. We were granted this and other never-before-given dispensations, as it became more and more apparent that 1.) a Disney movie was not just a movie but a business franchise, and 2.) The Consumer Products team could be trusted to apply good sense and good taste.

So, we made style guides, these big thick binders full of art and design elements, and sent them to our licensees. They took the art, and to differentiate their products from the other licensees’, would rejigger it and get creative with it — sometimes in very scary ways that we would try to fix.

My first project there was The Lion King. The licensees were all worried about the movie, because there was no princess. Mattel fretted that they couldn’t make dolls with long flowing locks. It shocked everyone when the movie was the biggest success Disney had had to date. The people heading the studio trusted my boss, so we had more leeway to break out of the traditional way of doing things than anyone had before. For example, all character art previous to The Lion King was drawn in blue pencil and then inked with a thick and thin brush line, like old-school animations cells. When I proposed using different art styles for the character art, the old guard muttered under their breath that it could not be done. But when we showed the producer of The Lion King an illustration of Simba in a rough woodcut style, he was delighted. So that door opened. And we brought in African flag colors and African tribal design motifs from textiles and art, even though there were no humans or evidence of humans in the movie. But those design elements made the design richer and more interesting, and the Studio went with it.

There were thousands and thousands of products (stuffed animals, toys, clothing, bedding, games, sippy cups, etc. etc. hauled around in red wagons and deposited in our offices, and my team looked at every single one of them. The character artists and designers both gave notes in triplicate on the forms attached to each item. I had one designer, who’d worked on choosing the colors for the L.A. Olympics, just working on advising the licensees about their color choices. It was surreal. We all took it super seriously, but at the same time were aware of the absurdity of it all. It was an epic feat of micro-management. Needless to say, not all the licensees were fans of the process.

It was funny to work in a serious place of business, at a Fortune 100 company, where everyone had to think like a child. What would a child want? Would a child enjoy playing with this toy? We would be in a meeting with Mattel, at this huge imposing conference table, discussing with utmost seriousness the amount of glitter on Dancing Esmeralda’s skirt. (Glitter appeared to be an occupational hazard of working at Mattel. Executives in suits with glitter on their cheeks!) Or fifteen grownups would be sitting around shooting little arrows at each other from Hercules action figures.

The job was stressful and fun at the same time.

Until it was stressful and not fun. I eventually became a VP. I was proud of achieving that, but then my job was all business. For some execs, business is their creative medium. Not me. I longed to be alone and make work with my own two hands. No meetings to go over sales reports or develop business strategies or to build consensus on those strategies. No group brainstorming sessions. No one was going to storm my brain but me.

I’m glad I stopped liking my job, because otherwise I would still be there. I wouldn’t have this new career that suits my nature so well. As an art student, the idea of a life spent alone in a studio agonizing over the left-hand corner of a painting filled me with despair. Now, that’s my idea of heaven!

Jules: That’s intense. And the copious amounts of glitter! (I once heard glitter referred to as the herpes of library story times, and it always makes me laugh when I think of it. There’s a bit of off-color humor before breakfast.)

I could talk to you all day, but I should wrap this up, since you a have life – and a busy and art-filled one at that.

My last question: What are you working on now? Anything you’re allowed to talk about?

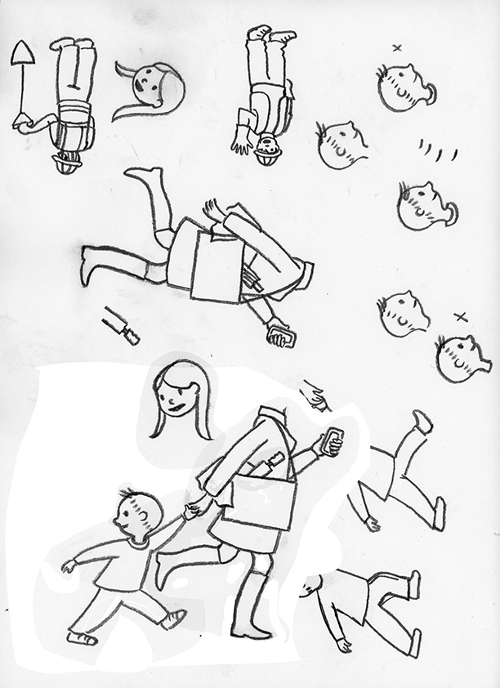

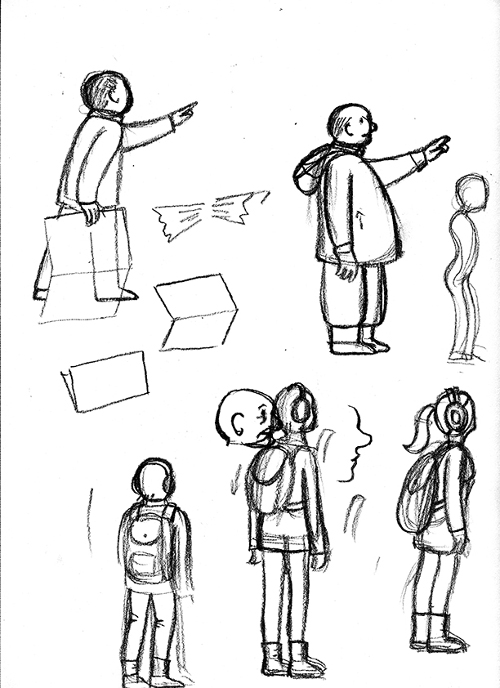

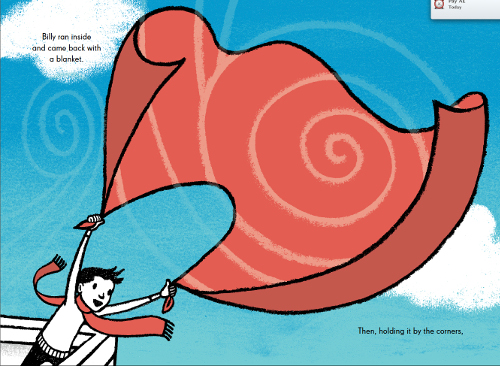

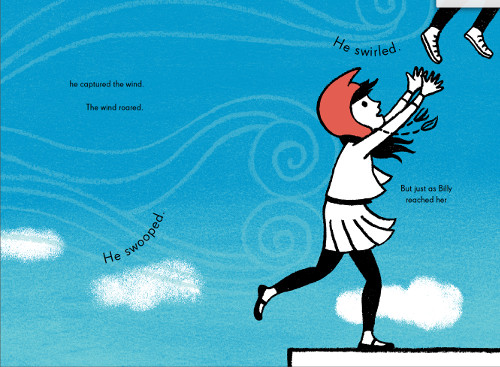

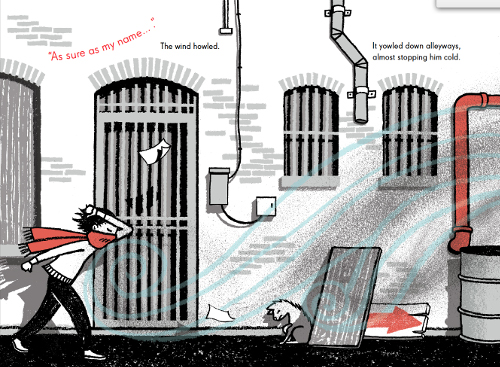

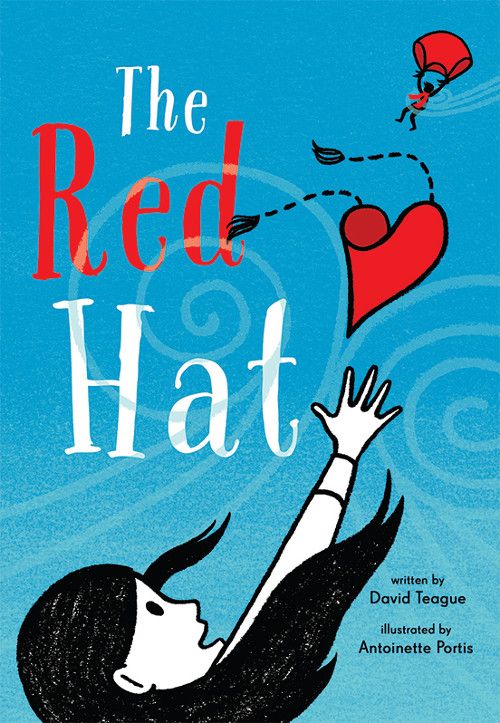

Antoinette: The Red Hat, a book written by David Teague that I illustrated, is coming out in December. It was surprisingly liberating to only have the pictures to worry about! It’s about a lonely boy, who struggles to connect with a girl who lives in the tower next door. The tone is kind of magic realism, set in a modern day city.

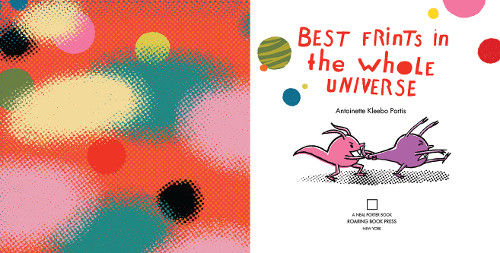

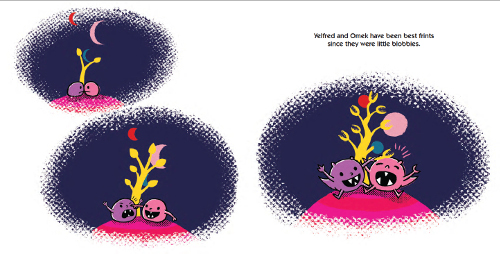

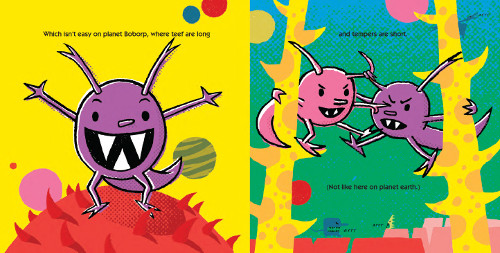

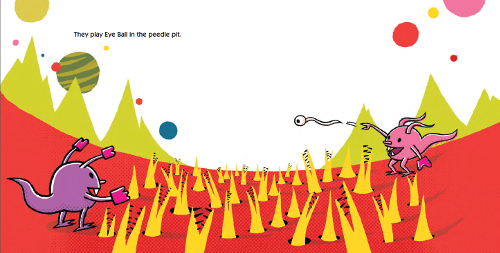

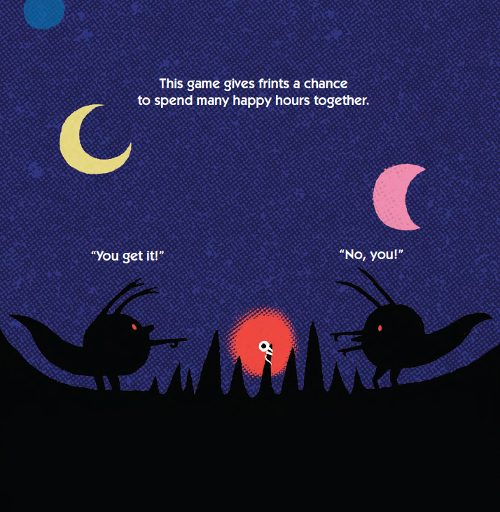

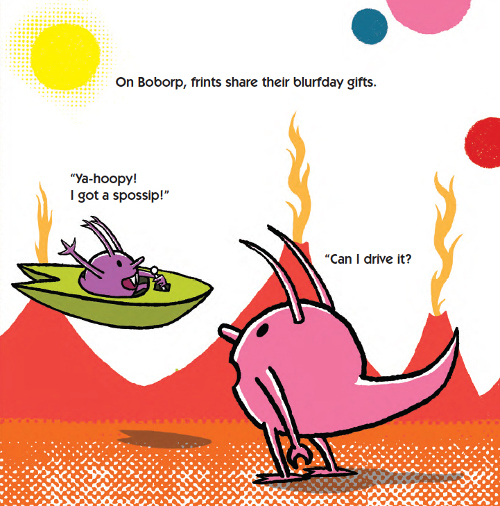

I’m excited about my next book with Neal Porter, Best Frints in the Whole Universe. Two best frints on an alien planet struggle to maintain their frintship through trials of their own making. (Just like friends on planet earth.)

When I was around 10 and had my first fight with a friend, I went home and announced to my dad that Debbie and I were done, finito. He told me that the mark of a real friendship is if you can have a fight and still be friends.

The whole situation instantly turned around for me. I had no idea that friends fought. I knew siblings did (I had four of the beasts), but the idea that someone you weren’t related to could get mad at you but still love you seemed impossible. And then—Dad wisdom—it wasn’t impossible. I don’t remember how Debbie and I made up. Probably I just went over to her house and started playing with her like nothing happened. In any case, we were great friends and shared imaginary adventures for years. We built rafts that sailed across seas of cement, lived in bush caves, hunted wooly mammoths with pointy sticks, wove floor mats out of iris leaves, and dyed cloth with berries. We shoved gardenia petals behind our ears for perfume.

My aliens, Omek and Yelfred, do not put gardenia petals behind their ears. They don’t have ears.

Frints is a real shift in tone from Wait. It’s funny. There’s an ironic narrator and two alien guys who behave like my brothers did — always competing, often fighting, and sometimes using their teeth (and not their words) to vent their anger. But there is a happy ending. Apparently, there is forgiveness on planet Boborp, just like here on planet Earth.

Jules: Thanks so much for visiting today, Antoinette!

WAIT. Copyright © 2015 by Antoinette Portis. Published by Neal Porter Books/Roaring Brook Press, New York. All images here reproduced by permission of Antoinette Portis.

I can’t “Wait!” to see this book. It appears different from “Wait! Wait!” another favorite of mine, but still has a quiet appeal to us. I have that, of course, moment, when I saw it was a Neal Porter Book. He understands picture books.

Thanks for the inside peak into Disney. Amazing. I wish I were an artist. Sigh.

Susan

Books4theCuriousChild.com

This interview is amazing! I learned so much as an illustrator, writer, and someone who works in the publishing industry. This is the interview I will keep coming back to read and read again. Thank you both Jules and Antoinette!

[…] Best Frints and shared a handful of spreads. So, if you want to check those out, they are here in this post — towards the […]

[…] to enlarge) I’ve got a review over at BookPage of Antoinette Portis’s new picture book, Now (Neal Porter Books/Roaring Brook, July 2017). That is […]