A Picture Book is a Machine:

Or, This Machine Tells Stories —

A Guest Post by Susan Rich

November 8th, 2016 by jules

November 8th, 2016 by jules

I admit I’m pretty choosy when it comes to handing the 7-Imp keyboard over to someone, but when I had the opportunity to hand it over to Susan Rich, Editor-at-Large for Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, I knew the answer was yes.

I admit I’m pretty choosy when it comes to handing the 7-Imp keyboard over to someone, but when I had the opportunity to hand it over to Susan Rich, Editor-at-Large for Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, I knew the answer was yes.

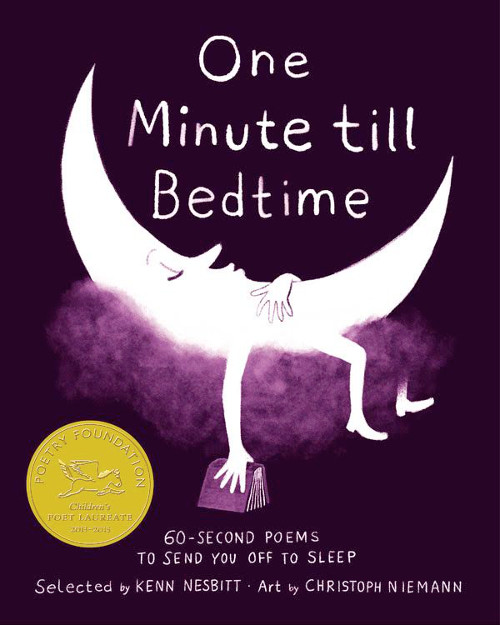

In honor of Picture Book Month, Susan is here to explore the mechanics of picture books — in more ways than one. I really enjoy what she has to say, and it all comes with art from Sophie Blackall, Frank Viva, and Christoph Niemann.

I thank her for temporarily taking over, while I fret over election results. Let’s get to it.

(Pictured here is an illustration from an upcoming book she has edited, illustrated by Niemann. More on that below.)

Susan: I’ve always admired machines. Especially the simple, time-tested ones. Like a Slinky, a perfect pencil sharpener, or a sturdy garlic press, items whose singular purpose is achieved through elegant mechanics. Look at this lovely hand crank-activated diorama, for example:

This small ship, animated to be steadily sailing over choppy waters, is deeply comforting — and a testament to the way that physical design and simple mechanics can execute the sublime. It’s only recently that I’ve realized that, as an editor, I am also something of a mechanic. Picture books are machines, too.

A machine is described as a tool containing one or more parts that uses energy to perform an intended action. The ingredients of a picture book—the text, the art, the design, and production—all come to physical life in a published book, and then come to mechanical life in the reading. The energy we apply to open the cover and turn the pages animates a story the way the tiny hand crank animates the ship on the water. Add to it a voice reading aloud, and our machine produces a multi-dimensional, multi-media experience.

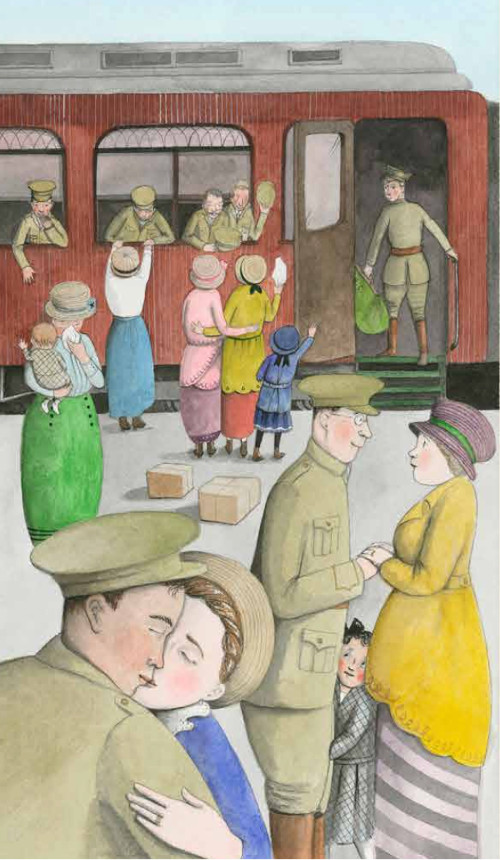

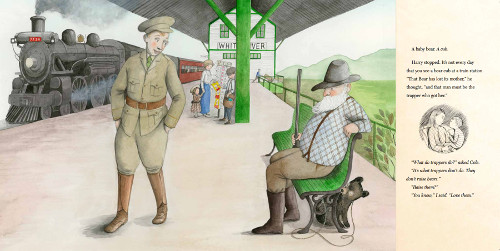

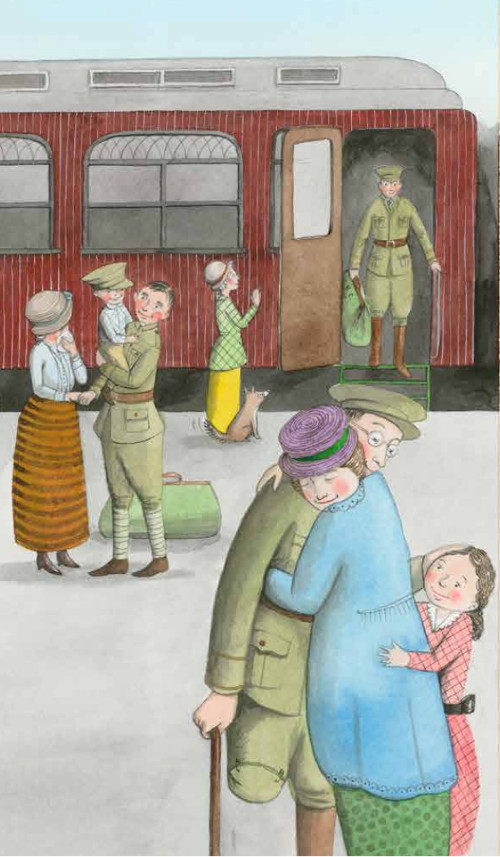

Consider the machine at work in Sophie Blackall’s Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear. In it, a train takes soldier Harry Colebourn across Canada on his way to war. Here, he boards the train with a final wistful look over his shoulder:

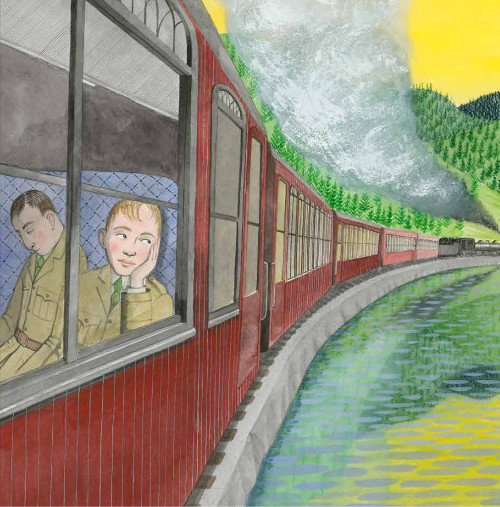

And then, off we go! The kinetic power of the page turn and the way we read a book from left to right launches the train’s locomotion. Each page turn takes the reader further east across Canada, chugging through the terrain …

… as well as through time:

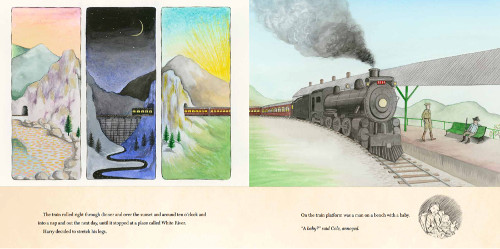

When the train pauses at White River Station, Harry gets out to stretch his legs. This is where he will make the audacious, history-making decision around which the book is built.

At this point, Sophie orchestrates one of my favorite page turns of all time, one like a curtain being drawn back to reveal a grand surprise. The book’s narrator, a mother telling a story to her son Cole, identifies the creature on the train platform, one the reader cannot see, as a baby. Cole, interrupts the story with some irritation. “A baby?”

Only the page turn can shift the reader’s perspective enough to reveal the creature that’s been hiding behind the trapper’s legs all along: a baby bear. A cub. Enter Winnie.

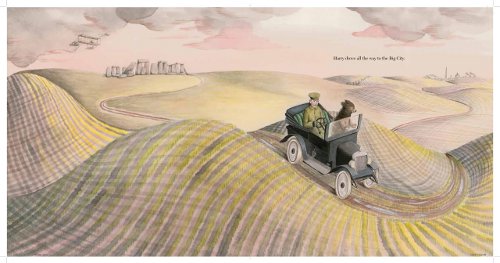

The book’s journey continues moving through time and space, left-to-right, propelled by page turns — sailing across the ocean, marching over the soggy Salisbury Plain, and zooming in a car passing Stonehenge on route to the London Zoo.

It is a journey that doesn’t conclude until we reach another beautiful and revealing page turn. Hearing all about what became of Winnie at the zoo, Cole asks, “But what about Harry?” And the page turn that follows transports us to our final stop: back to Harry, back to the story’s origin.

This final page turn returns to the same train platform where it all began, bookending our journey just like a real round trip. Poignantly, though, this time, the scene reveals how much has changed and hints at the brutal cost of the war. It’s an exquisite bit of storytelling. The machine took us on adventure — and brought us back home.

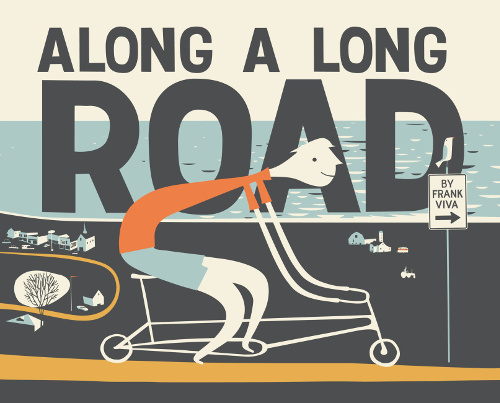

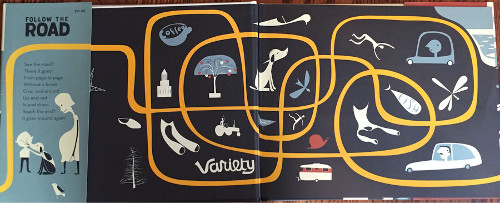

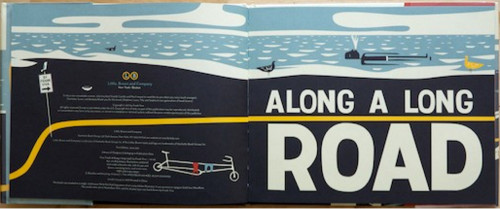

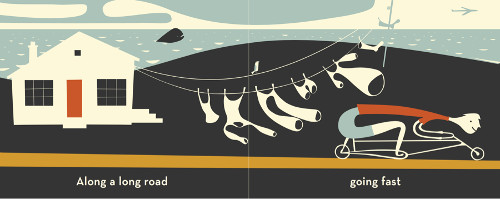

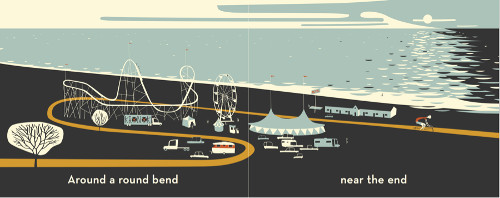

The mechanism of movement also propels Frank Viva’s Along a Long Road. [Quick Note from Jules: Click here at this previous 7-Imp post to see some of Frank’s early sketches from this book.] This book is a marvelous machine, created from 35 feet of continuous art. Here, we join a cyclist on an unbroken road that moves speedily from the front cover …

… over to the front jacket flap and through the endpapers …

… across the title page …

… and then speeds off, left to right, through the book — on a ride that will loop all the way beyond the last page, right across the endpapers, over the jacket flaps and around again, all the way back to the start of the book.

The machine does its job so well that it can move a child through the story, even if they don’t yet know how to read. This machine’s design introduces the mechanical essence of reading a book: Follow the bike and you’re automatically following the story in order from left-to-right through pages. Ta da! You are moving through a book like a reader. Many of Frank Viva’s books work like machines -– A Long Way Away and Outstanding in the Rain are both mechanical wonders.

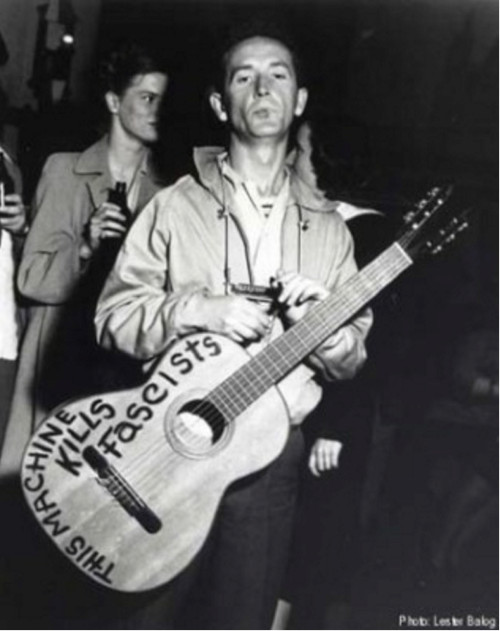

I have a new machine coming out this month, One Minute till Bedtime: 60-Second Poems to Send You off to Sleep. This is a beautiful anthology of poems, selected by former Children’s Poet Laureate Kenn Nesbitt, with art by the award-winning artist and designer Christoph Niemann. This one brings to mind for me another elegant machine, Woody Guthrie’s guitar, which famously read, “This machine kills fascists.”

If I could scrawl a similar message across the cover of One Minute till Bedtime, it would read, “This machine puts children to sleep.”

The simple part of this machine’s conceit is that with tiny pieces of beautiful poetry to offer, the endless nighttime call for “Just one more story!” can be answered with expediency. Added to the bedtime routine, the last one-minute poem of the night can be part of a weary caregiver’s exit plan. It’s the goodness of poetry meets the classic tongue in cheek bestseller Go the F**k to Sleep!

In its finer workings, though, there is a gear that simulates the act of falling asleep. It seems that when we begin to rest our minds, our first thoughts are often of the day that has past: the real, practical details of our lives. Then, thoughts begin to wander, jumping from one topic to a related one. Gradually, the associations and our thoughts start to make less sense. Thoughts become less grounded in reality on the way towards free association and dreaming. Kenn wired this into the book’s mechanics in the arrangement of the poems. Each of the book’s seven sections tracks a journey to sleep.

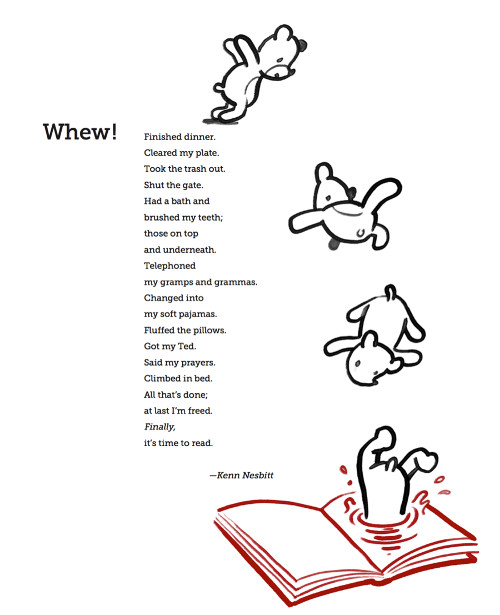

So, a section might begin with a poem like this one, by Kenn himself, about the to-do list completed for bedtime:

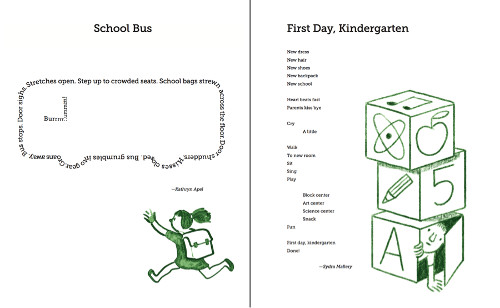

The order of poems mimics our thoughts in the way that one topic will lead to a related one, as with this pairing:

Later in a section, we find ourselves in the realm of nonsense, the stuff that dreams are made of:

Also further along within sections are a number of lullaby poems, which give the listener permission to truly nod off:

As it goes with falling asleep, the ordering here doesn’t strictly adhere to rules but, as I’ve discovered putting this machine into practice, there is something undoubtedly calming about feeding poetry to a weary brain.

To celebrate the book’s publication, Christoph Niemann created a brilliant animation, one that employs the mechanical joy of a simple machine itself — an hourglass. I will conclude my meditation on storytelling machines with this soothing, satisfying machine at work.

And indeed, watch this animation, or read One Minute till Bedtime, and I guarantee that, eventually, you will be asleep.

All images used by permission of Susan Rich.

How/where do I purchase one of those boat dioramas?

Evidently, they are here:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/BeBraveMakeWaves.